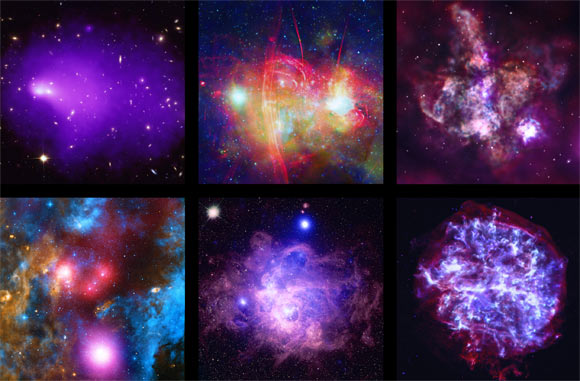

On July 23, 1999, NASA’s Space Shuttle Columbia blasted off from the Kennedy Space Center carrying the agency’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. Twenty years later, a collection of new images was released by NASA to commemorate this milestone. These images represent the breadth of Chandra’s exploration, demonstrating the variety of objects it studies as well as how X-rays complement the data collected in other types of light.

Chandra’s 20th anniversary images (from left to right). Top row: Abell 2146, the result of a collision and merger between two galaxy clusters; the central region of our Milky Way Galaxy; and 30 Doradus, which is nicknamed the Tarantula Nebula, a large star-forming region in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Bottom row: Cygnus OB2, a group of extremely massive and luminous stars; NGC 604, a star-forming region in the nearby galaxy Messier 33; and G292.0+1.8 is a rare type of supernova remnant. Image credit: NASA / CXC.

Chandra is one of NASA’s Great Observatories — along with the Hubble Space Telescope, Spitzer Space Telescope, and Compton Gamma Ray Observatory — and has the sharpest vision of any X-ray telescope ever built.

It is specially designed to detect X-ray emission from very hot regions of the Universe such as exploded stars, clusters of galaxies, and matter around black holes.

Because X-rays are absorbed by Earth’s atmosphere, Chandra must orbit above it, up to an altitude of 86,500 miles (139,000 km) in space.

Chandra is often used in conjunction with telescopes like Hubble and Spitzer that observe in different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, and with other high-energy missions like ESA’s XMM-Newton and NASA’s NuSTAR.

The Smithsonian’s Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, MA, hosts the Chandra X-ray Center which operates the satellite, processes the data, and distributes it to scientists around the world for analysis.

Chandra was originally proposed to NASA in 1976 by Riccardo Giacconi, recipient of the 2002 Nobel Prize for Physics based on his contributions to X-ray astronomy, and Harvey Tananbaum, who would become the first director of the Chandra X-ray Center.

It took decades of collaboration — between scientists and engineers, private companies and government agencies, and more — to make Chandra a reality.

“In this year of exceptional anniversaries — 50 years after Apollo 11 and 100 years after the solar eclipse that proved Einstein’s general theory of relativity — we should not lose sight of one more,” said Dr. Paul Hertz, Director of Astrophysics at NASA.

“Chandra was launched 20 years ago, and it continues to deliver amazing science discoveries year after year.”

Chandra’s discoveries have impacted virtually every aspect of astrophysics.

For example, Chandra was involved in a direct proof of dark matter’s existence. It has witnessed powerful eruptions from supermassive black holes. Astronomers have also used Chandra to map how the elements essential to life are spread from supernova explosions.

Many of the phenomena Chandra now investigates were not even known when the telescope was being developed and built. For example, astronomers now use Chandra to study the effects of dark energy, test the impact of stellar radiation on exoplanets, and observe the outcomes of gravitational wave events.

“Chandra remains peerless in its ability to find and study X-ray sources,” said Chandra X-ray Center Director Dr. Belinda Wilkes.

“Since virtually every astronomical source emits X-rays, we need a telescope like Chandra to fully view and understand our Universe.”