A team of astronomers led by Dr Alessandro Papitto from the Institute of Space Studies of Barcelona has discovered a fast-spinning pulsar that switches between emitting X-rays and emitting radio waves. This is the first direct evidence of one kind of pulsar turning into another.

The pulsar, labeled PSR J1824-2452I, lies 18,000 light-years away in a small globular cluster of stars known as Messier 28 in the constellation of Sagittarius.

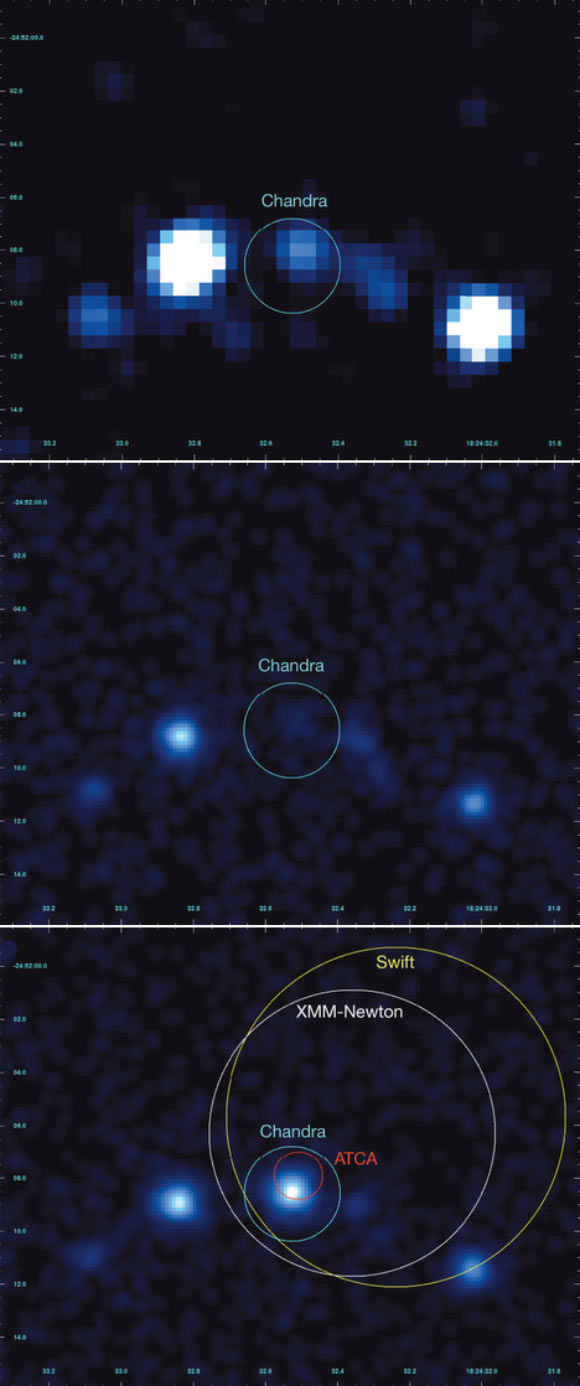

It was initially detected as an X-ray source with ESA’s INTEGRAL satellite. X-ray pulsations were seen with another satellite, ESA’s XMM-Newton. Further observations were made with NASA’s Swift. NASA’s Chandra X-ray telescope got a precise position for the object.

Then, crucially, the object was checked against the pulsar catalogue generated by CSIRO’s Australia Telescope National Facility, and other pulsar observations. This established that it had already been identified as a radio pulsar.

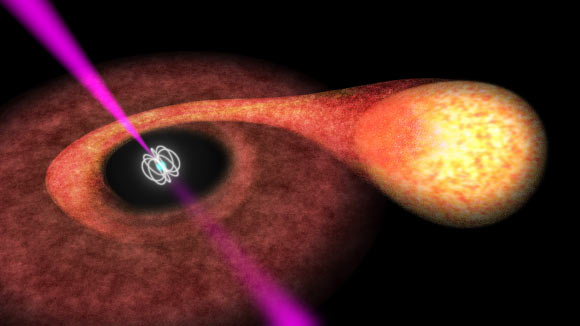

PSR J1824-2452I has a tiny companion star, with about a fifth the mass of the Sun. Although small, the companion is fierce, pounding the pulsar with streams of matter.

Images of the core of Messier 28 taken during 04 August 2002, 27 May 2006 and 29 April 2013 (A. Papitto et al).

Normally the pulsar shields itself from this onslaught, its magnetic field deflecting the matter stream into space. But sometimes the stream swells to a flood, overwhelming the pulsar’s protective ‘force field’. When the stream hits the pulsar’s surface its energy is released as blasts of X-rays. Eventually the torrent slackens. Once again the pulsar’s magnetic field re-asserts itself and fends off the companion’s attacks.

“We’ve been fortunate enough to see all stages of this process, with a range of ground and space telescopes. We’ve been looking for such evidence for more than a decade,” said Dr Papitto, who with colleagues reported the discovery in the journal Nature.

PSR J1824-2452I and its companion form what is called a ‘low-mass X-ray binary’ system. In such a system, the matter transferred from the companion lights up the pulsar in X-rays and makes it spin faster and faster, until it becomes a ‘millisecond pulsar’ that spins at hundreds of times a second and emits radio waves. The process takes about a billion years, astronomers think.

In its current state PSR J1824-2452I is exhibiting behavior typical of both kinds of systems: millisecond X-ray pulses when the companion is flooding the pulsar with matter, and radio pulses when it is not.

“It’s like a teenager who switches between acting like a child and acting like an adult,” said study co-author Mr John Sarkissian of CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science.

“Interestingly, the pulsar swings back and forth between its two states in just a matter of weeks.”

______

Bibliographic information: A. Papitto et al. 2013. Swings between rotation and accretion power in a binary millisecond pulsar. Nature 501, 517–520; doi: 10.1038/nature12470