Marine biologists from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) and three Canadian research organizations have described four new species of carnivorous sponges: Asbestopluma monticola, Asbestopluma rickettsi, Cladorhiza caillieti and Cladorhiza evae.

Biologists first discovered that some sponges are carnivorous about 20 years ago. Since then only 7 species have been found in the northeastern Pacific.

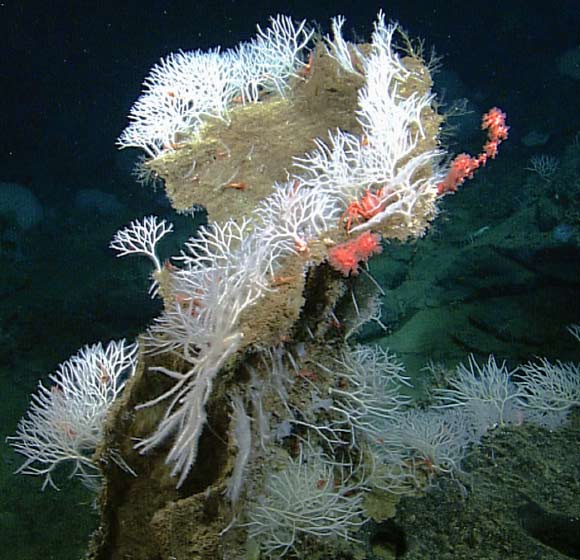

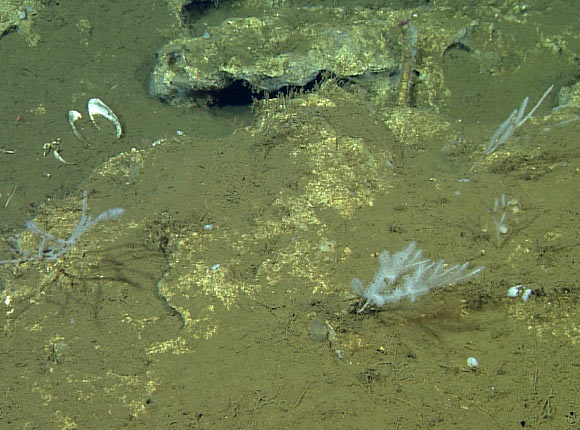

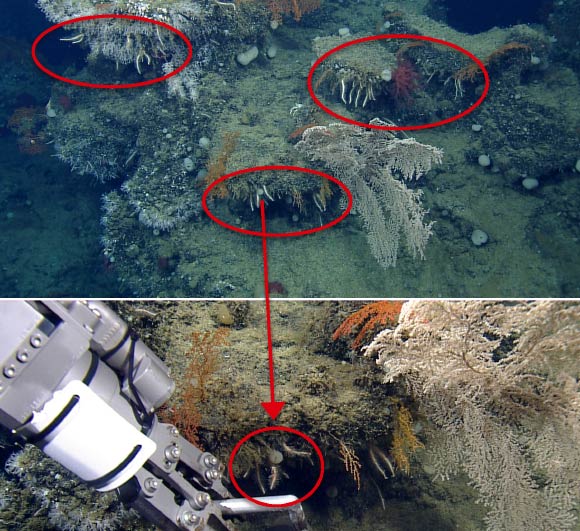

These sponges look like bare twigs or small shrubs covered with tiny hairs. But the hairs consist of tightly packed bundles of microscopic hooks that trap small animals such as shrimp-like amphipods. Once a marine animal becomes trapped, it takes only a few hours for sponge cells to begin engulfing and digesting it. After several days, all that is left is an empty shell.

In 2013, MBARI marine biologists and their Canadian colleagues used remotely operated vehicles to collect specimens of four new carnivorous sponges living on the deep seafloor, from the Pacific Northwest to Baja California.

Two species of the genus Asbestopluma – Asbestopluma monticola and Asbestopluma rickettsi – were collected off California, USA.

One species of the genus Cladorhiza, named Cladorhiza evae, was collected at a newly discovered hydrothermal vent field in the Gulf of California, Mexico. A second species of the genus, named Cladorhiza caillieti, was collected from the Endeavor Segment of the Juan de Fuca Ridge, Canada.

Back in the lab, when the scientists looked closely at the collected sponges, they discovered numerous crustacean prey in various states of decomposition.

Sponges are generally filter feeders, living off of bacteria and single-celled organisms sieved from the surrounding water. They contain specialized cells called choancytes, whose whip-like tails move continuously to create a flow of water which brings food to the sponge. However, most carnivorous sponges have no choancytes.

“To keep beating the whip-like tails of the choancytes takes a lot of energy. And food is hard to come by in the deep sea. So these sponges trap larger, more nutrient-dense organisms, like crustaceans, using beautiful and intricate microscopic hooks,” said Dr Lonny Lundsten, a marine biologist from MBARI and the lead author of the paper published in the journal Zootaxa (full paper in .pdf).

The spikiness of two these sponges, Asbestopluma monticola and Asbestopluma rickettsi, is reflected in the name of their genus.

Asbestopluma monticola was first collected from the top of Davidson Seamount, an extinct underwater volcano off the Central California coast (monticola means ‘mountain-dweller’ in Latin).

Asbestopluma rickettsi was named after marine biologist Ed Ricketts, who was immortalized in John Steinbeck’s book, Cannery Row. This sponge was observed at two locations offshore of Southern California. At one of these spots, the sponge was living near colonies of clams and tubeworms that use bacteria to obtain nutrition from methane seeping out of the seafloor.

Although Asbestopluma rickettsi has spines, the scientists did not see any animals trapped on the specimens they collected. Ongoing research suggests that this sponge, like its ‘chemosynthetic’ neighbors, can use methane-loving bacteria as a food source.

Cladorhiza evae and Cladorhiza caillieti were also observed near communities of chemosynthetic animals. However these communities were associated with deep-sea hydrothermal vents, where plumes of hot, mineral-rich water flow out of the seafloor.

Specimens of both these sponges had numerous prey trapped among their spines.

Although it’s clear that the sponges with trapped animals were consuming their crustacean prey, the marine biologists are looking forward to the day when they will actually get to see this process in action.

______

Lundsten L. et al. 2014. Four new species of Cladorhizidae (Porifera, Demospongiae, Poecilosclerida) from the Northeast Pacific. Zootaxa 3786 (2): 101–123; doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3786.2.1