‘Superbolts’ are distinct from typical lightning flashes and can be more than 1,000 times brighter, according to two new papers published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres.

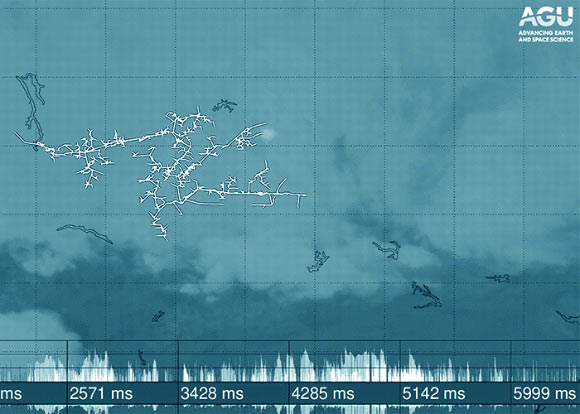

This image from the Geostationary Lightning Mapper shows a superbolt-producing lightning flash over the southeastern United States on February 19, 2019. The lightning flash spanned several hundred kilometers and lasted nearly 7 seconds. Image credit: Los Alamos National Laboratory.

In 1977, U.S. scientist Turman Bobby identified lightning that was 100 times brighter than normal in the data from the bomb-monitoring Vela satellites.

This observation sparked a debate as to whether these ‘superbolt’ events resulted from some undiscovered exotic lightning process (new physics), whether they were produced by a particular type of lightning event enabled by favorable conditions in the electrified cloud (unique physics), or whether superbolts were just normal lightning in ordinary storms that happen to have been observed by an on-orbit sensor with an unobstructed view of the hot lightning channel (normal lightning).

“When you see a lightning flash from space, it will look a lot dimmer than if you were to see it from ground level because the clouds block some of the light,” said Los Alamos National Laboratory remote-sensing scientist Dr. Michael Peterson, lead author of both studies.

“We propose that superbolts typically result from rare positively charged cloud-to-ground events, rather than the more common negatively charged cloud-to-ground events characteristic of most lightning.”

In the first study, Dr. Peterson and his colleague, Dr. Erin Lay of Los Alamos National Laboratory, used the Geostationary Lightning Mapper onboard GOES-16 satellite to measure the optical energy of lightning from space.

They analyzed two years of continuous measurements — from January 2018 through January 2020 — from across the Americas.

They found that a myriad of lighting processes can produce a superbolt: intracloud pulses and cloud-to-ground strokes with a range of peak currents.

However, the absolute brightest cases — at least 1,000x more energetic than normal — cluster in certain regions that are known for very large thunderstorms.

“One lightning stroke even exceeded 3 terawatts of power — thousands of times stronger than ordinary lightning detected from space,” Dr. Peterson said.

“Understanding these extreme events is important because it tells us what lightning is capable of.”

In the second study, Dr. Peterson and Dr. Matt Kirkland of Los Alamos National Laboratory analyzed the data from the Fast On-Orbit Detection of Transient Events (FORTE) satellite to garner a better understanding of superbolts.

“We found that weaker superbolts result from both scenarios: some come from normal lightning, while others are caused by strong cloud-to-ground strokes that tend to occur in oceanic regions, in the winter, and often near the coast of Japan,” they said.

“The most powerful superbolts, however, predominantly come from strong strokes and may still merit the superbolt distinction.”

_____

Michael Peterson & Erin Lay. Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM) Observations of the Brightest Lightning in the Americas. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, published online November 12, 2020; doi: 10.1029/2020JD033378

Michael Peterson & Matt W. Kirkland. Revisiting the Detection of Optical Lightning Superbolts. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, published online November 12, 2020; doi: 10.1029/2020JD033377