212-million-year-old fossils discovered in New Mexico confirm that Drepanosaurus, a Late Triassic tree-dwelling reptile, was a small-bodied creature with a fearsome finger. The second digit of its forelimb sported a huge claw.

Drepanosaurus unguicaudatus rips away tree bark with its huge claw and powerful arm. Image credit: Victor Leshyk.

Yale University researcher Dr. Adam Pritchard and co-authors analyzed a series of three-dimensionally preserved forelimbs and isolated forelimb bones of Drepanosaurus (full name Drepanosaurus unguicaudatus) that were discovered at the Hayden Quarry in the Chinle Formation of New Mexico.

Their findings were published online September 29, 2016 in the journal Current Biology.

Drepanosaurus was previously known only from Italy, where a badly crushed skeleton was collected at Endenna cave in the Zorzino Limestone Formation in 1980.

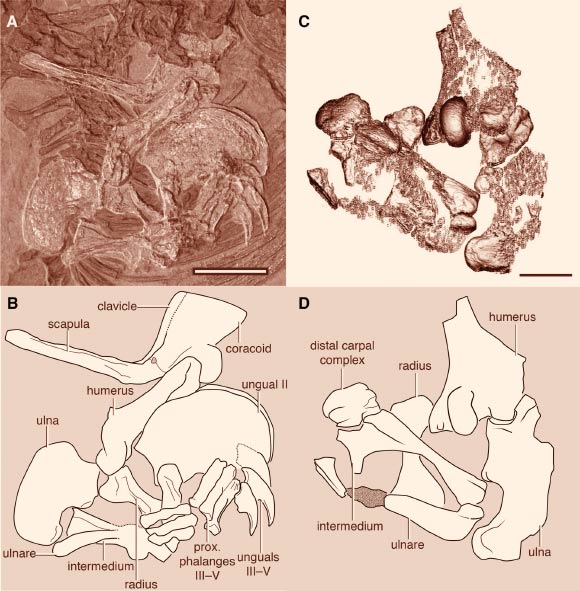

Forelimb specimens of Drepanosaurus unguicaudatus from the Zorzino Limestone (A-B) and Chinle Formation (C-D). Scale bars – 2 cm. Image credit: Adam C. Pritchard et al.

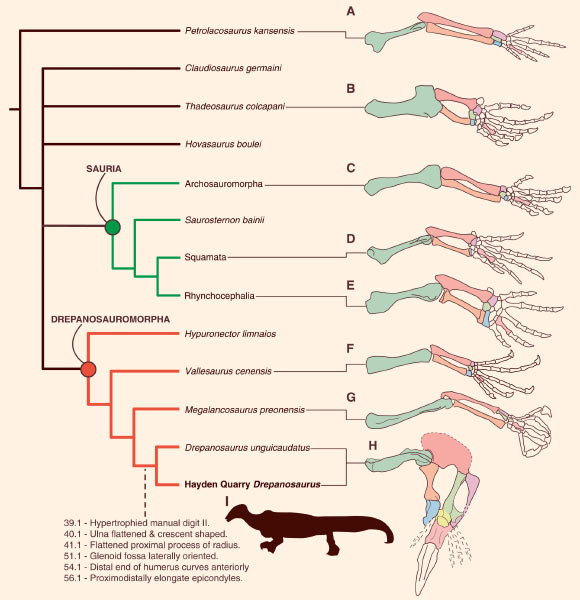

The ancient creature is neither a dinosaur nor a lizard. It is a member of Drepanosauromorpha, a group of Triassic reptiles with lizard-like body proportions and elongate, slender digits likely adapted for specialized grasping.

“Drepanosaurus stretches the bounds of what we think can evolve in the limbs of four-footed animals,” Dr. Pritchard said.

“Ecologically, Drepanosaurus seems to be a sort of chameleon-anteater hybrid, which is really bizarre for the time. It possesses a totally unique forelimb.”

Four-limbed animals with a backbone are called tetrapods. In nearly all tetrapods, the forearm is made up of two, elongate and parallel bones — the radius and the ulna. These bones connect to a series of much shorter, wrist bones at the base of the hand.

Phylogenetic affinities of Drepanosaurus unguicaudatus and forelimb diversity of Diapsida. Image credit: Adam C. Pritchard et al.

Drepanosaurus, however, has radius and ulna bones that are not parallel. Instead, the ulna is a flat, crescent-shaped bone. Also, the two wrist bones that meet the end of the ulna are long rather than short. They are longer than the radius, in fact.

“The bone contacts suggest that the enlarged claw of Drepanosaurus could have been hooked into insect nests,” Dr. Pritchard said.

“The entire arm could then have been powerfully retracted to tear open the nest. This motion is very similar to the hook-and-pull digging of living anteaters, which also eat insects.”

Drepanosaurus also had grasping feet and a claw-like structure at the tip of its tail.

The findings suggest that tetrapods developed specialized, modern ecological roles more than 200 million years ago.

_____

Adam C. Pritchard et al. Extreme Modification of the Tetrapod Forelimb in a Triassic Diapsid Reptile. Current Biology, published online September 29, 2016; doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.084