A new study led by the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) provides the strongest evidence to date that sharks arose from a group of bony fishes called Acanthodii (acanthodians, or ‘spiny sharks’).

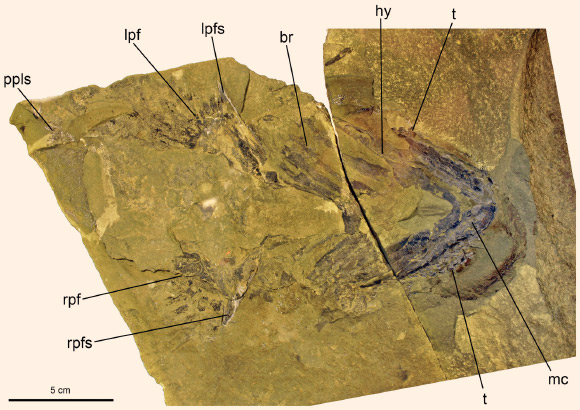

General view of the Doliodus problematicus specimen, showing the ventral part of the individual viewed in dorsal aspect, with major features identified. Abbreviations: br – branchial arches, hy – hyoid arch, lpf – left pectoral fin, lpfs – left pectoral fin spine, mc – meckelian cartilage of lower jaw, ppls – prepelvic spines, rpfs – right pectoral fin spine, rpf – right pectoral fin, t – teeth. Scale bar – 5 cm. Image credit: John G. Maisey et al.

Analyzing a well-preserved fossil of Doliodus problematicus, a sharklike fish that lived 400-397 million years ago (Devonian period), AMNH curator John Maisey and co-authors identified it as an important transitional species that points to sharks as ancanthodians’ living descendants.

“Major vertebrate evolutionary transitions, such as ‘fin to limb’ and ‘dinosaur to bird’ are substantiated by numerous fossil discoveries. By contrast, the much earlier rise of sharklike fishes within jawed vertebrates is poorly documented,” Dr. Maisey said.

“Although this ‘fish to fish’ transition involved less profound anatomical reorganization than the evolutions of tetrapods or birds, it is no less important for informing the evolutionary origins of modern vertebrate diversity.”

In 2003, this question in vertebrate evolution was revitalized by the discovery of a remarkable fossil skeleton of Doliodus problematicus in New Brunswick, Canada.

When its discovery was announced, Doliodus problematicus was shown to have paired spines in front of its pectoral (shoulder) fins, a feature otherwise known mainly in acanthodians.

But in 2009 and 2014, Dr. Maisey and his colleagues determined that the animal’s head, skeleton, and teeth were actually more like those of sharks than acanthodians.

The new study, based on computed tomography (CT) imaging, uncovered even more spines that are buried inside the matrix of the fossil.

These spines likely lined the underside of the fish, a distinguishing characteristic of acanthodians that confirms the fossil is evidence of an important transitional species.

“The arrangement of these spines shows unequivocally that this fish was basically an acanthodian with a shark’s head, pectoral skeleton, and teeth,” Dr. Maisey said.

The study was published in the journal American Museum Novitates on March 10, 2017.

_____

John G. Maisey et al. 2017. Pectoral morphology in Doliodus: bridging the ‘acanthodian’-chondrichthyan divide. American Museum Novitates 3875