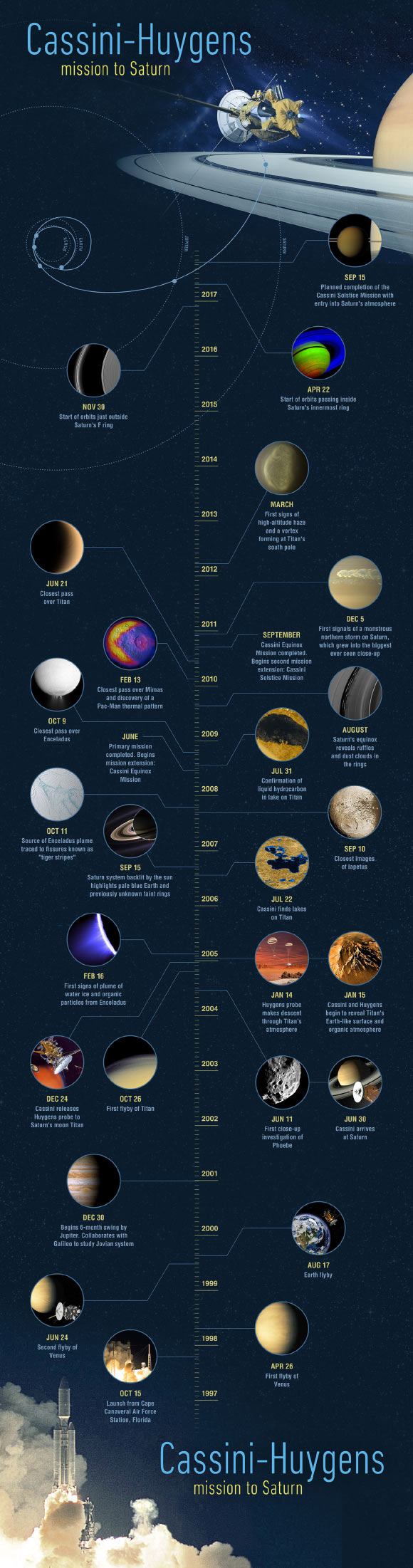

Today, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft made its final approach to Saturn and dove into the gas giant’s atmosphere. Loss of contact with the orbiter took place at 7:55:46 a.m. EDT (4:55:46 a.m. PDT, 11:55:46 a.m. GMT, 1:55:46 p.m. CEST), with the signal received by NASA’s Deep Space Network antenna complex in Canberra, Australia.

Cassini’s plunge brings to a close a series of 22 weekly ‘Grand Finale’ dives between Saturn and its rings, a feat never before attempted by any spacecraft.

Telemetry received during the plunge indicates that, as expected, Cassini entered Saturn’s atmosphere with its thrusters firing to maintain stability.

As planned, data from eight of Cassini’s science instruments was beamed back to Earth. Mission scientists will examine the spacecraft’s final observations in the coming weeks for new insights about Saturn, including hints about the planet’s formation and evolution, and processes occurring in its atmosphere.

“This is the final chapter of an amazing mission, but it’s also a new beginning,” said Dr. Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

“Cassini’s discovery of ocean worlds at Titan and Enceladus changed everything, shaking our views to the core about surprising places to search for potential life beyond Earth.”

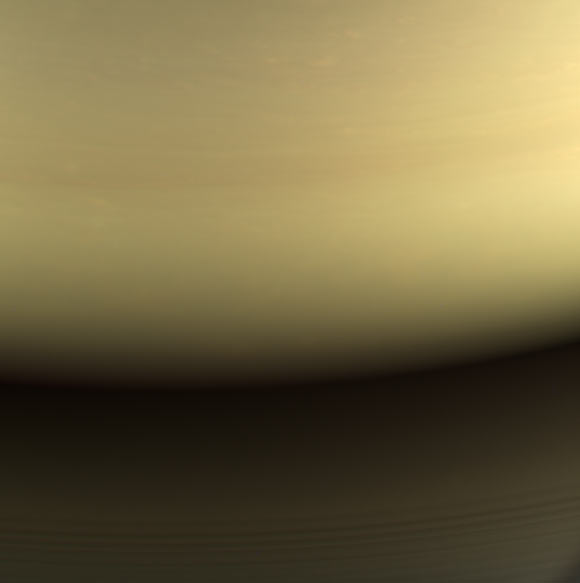

This view is the last image taken by the imaging cameras on NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. The cameras obtained this view at approximately the same time that Cassini’s visual and infrared mapping spectrometer made its own observations of the impact area in the thermal infrared. This location — the site of Cassini’s atmospheric entry — was at this time on the night side of the planet, but would rotate into daylight by the time Cassini made its final dive into Saturn’s upper atmosphere, ending its remarkable 13-year exploration of Saturn. The view was acquired on September 14, 2017 at 19:59 UTC at a distance of 394,000 miles (634,000 km) from Saturn. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute.

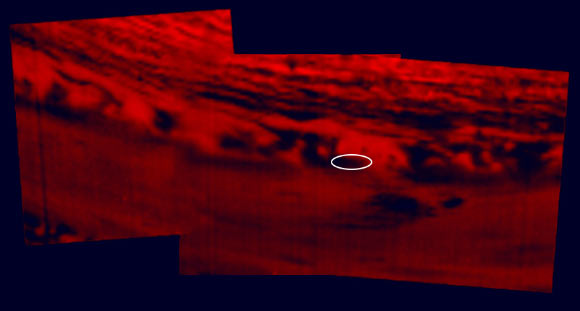

This montage of images, made from data obtained by Cassini’s visual and infrared mapping spectrometer, shows the location on Saturn where the spacecraft entered the planet’s atmosphere. Cassini entered the atmosphere at 9.4 degrees north latitude, 53 degrees west longitude. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona.

“It’s a bittersweet, but fond, farewell to a mission that leaves behind an incredible wealth of discoveries that have changed our view of Saturn and our Solar System, and will continue to shape future missions and research,” said Dr. Michael Watkins, director of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

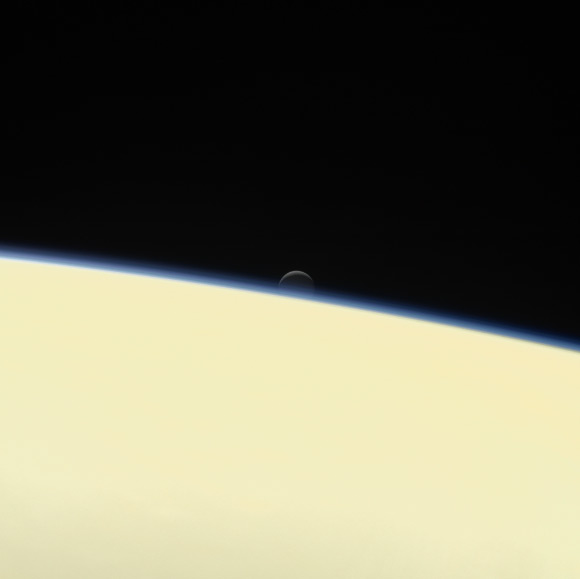

Saturn’s active, ocean-bearing moon Enceladus sinks behind the giant planet in a farewell portrait from Cassini. This view of Enceladus was taken by the spacecraft on September 13, 2017. The image was taken using Cassini’s narrow-angle camera at a distance of 810,000 million miles (1.3 million km) from Enceladus and about 620,000 miles (1 million km) from Saturn. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute.

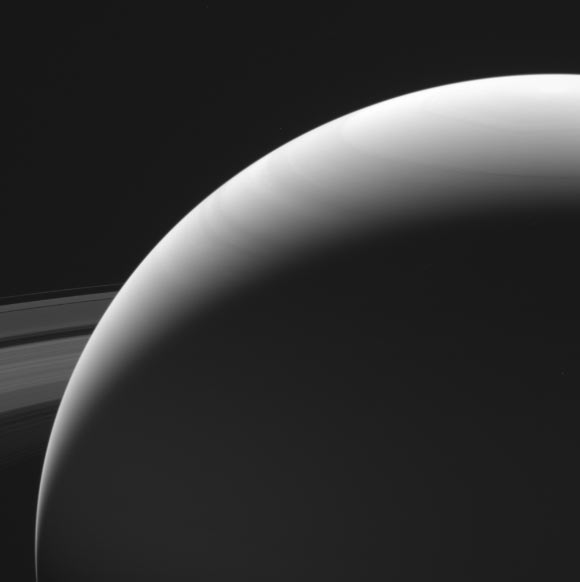

This image of Saturn’s northern hemisphere was taken by Cassini on September 13, 2017. The view was taken in visible red light using Cassini’s wide-angle camera at a distance of 684,000 miles (1.1 million km) from Saturn. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute.

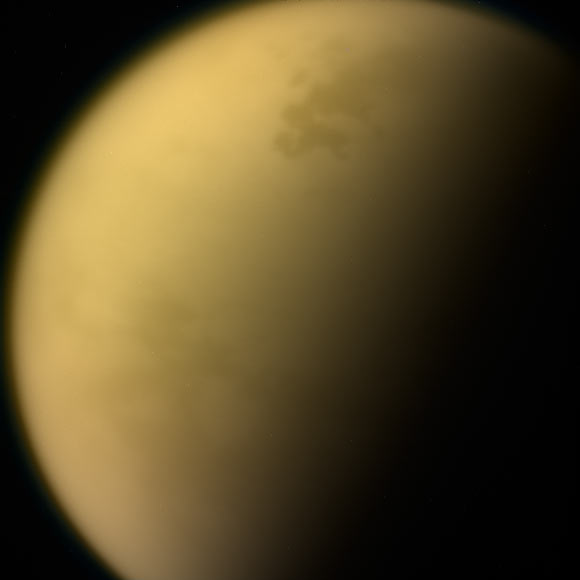

As it glanced around the Saturn system one final time, Cassini captured this view of Titan. The view was obtained by Cassini’s narrow-angle camera on September 13, 2017 at a distance of 481,000 miles (774,000 km) from Titan. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute.

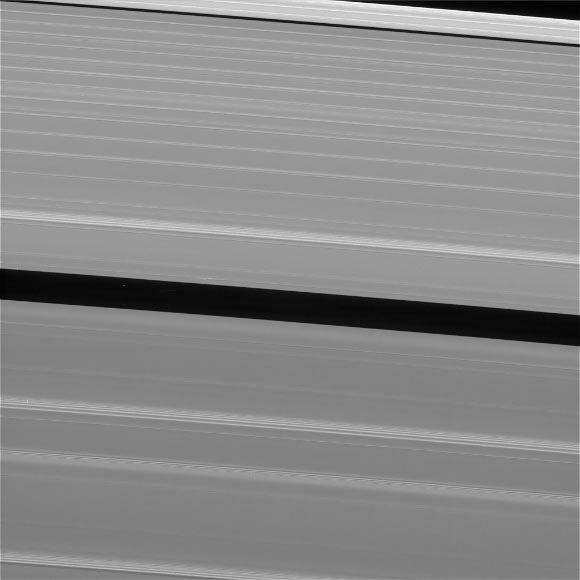

This view of Saturn’s A ring features a lone ‘propeller’ — one of many such features created by small moonlets embedded in the rings as they attempt, unsuccessfully, to open gaps in the ring material. The image was taken by Cassini on September 13, 2017. The view was taken in visible light using Cassini’s wide-angle camera at a distance of 420,000 miles (676,000 km) from Saturn. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute.

This image of Saturn’s outer A ring features the small moon Daphnis and the waves it raises in the edges of the Keeler Gap. The image was taken by Cassini on September 13, 2017. The view was taken in visible light using Cassini’s wide-angle camera at a distance of 486,000 miles (782,000 km) from Saturn. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute.

“The Cassini operations team did an absolutely stellar job guiding the spacecraft to its noble end,” said Cassini project manager Dr. Earl Maize, also of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“From designing the trajectory seven years ago, to navigating through the 22 nail-biting plunges between Saturn and its rings, this is a crack shot group of scientists and engineers that scripted a fitting end to a great mission. What a way to go. Truly a blaze of glory.”

“Things never will be quite the same for those of us on the Cassini team now that the spacecraft is no longer flying,” said Cassini project scientist Dr. Linda Spilker, of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“But, we take comfort knowing that every time we look up at Saturn in the night sky, part of Cassini will be there, too.”

Now that Cassini is gone, most of the team’s engineers are migrating to other planetary missions, where they will continue to contribute to the work we’re doing to explore our Solar System and beyond. Mission scientists will keep working for the coming years to ensure that we fully understand all of the data acquired during the mission’s Grand Finale. They will carefully calibrate and study all of the data so that it can be entered into the Planetary Data System. From there, it will be accessible to future scientists for years to come. Image credit: NASA.

“Cassini may be gone, but its scientific bounty will keep us occupied for many years,” Dr. Spilker added.

“We’ve only scratched the surface of what we can learn from the mountain of data it has sent back over its lifetime.”