The Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument onboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft has captured the first infrared images of the north pole of Ganymede, the largest moon in the Solar System and one of the four Galilean moons of Jupiter.

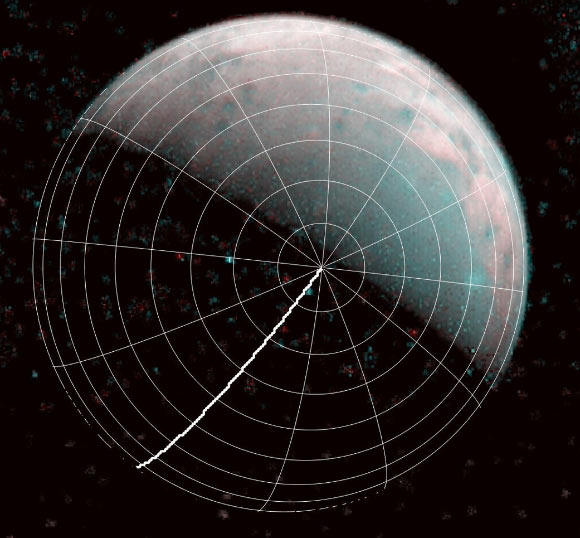

The north pole of Ganymede can be seen in center of this image taken by the JIRAM infrared imager aboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft on December 26, 2019. The thick line is 0-degrees longitude. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / SwRI / ASI / INAF / JIRAM.

Discovered in 1610, Ganymede has a diameter of 5,268 km (3,273 miles), around 8% larger than that of the planet Mercury and much larger than Pluto.

This Jovian satellite has three main layers: a sphere of metallic iron at the center, a spherical shell of rock (mantle) surrounding the core, and a spherical shell of mostly ice surrounding the rock shell and the core. The ice shell on the outside is very thick, maybe 800 km (497 miles) thick.

Ganymede is the only moon in the Solar System to have its own magnetic field, which causes aurorae in regions circling its north and south poles.

As Ganymede has no atmosphere, the surface at its poles is constantly being bombarded by plasma from the magnetosphere of Jupiter. This bombardment has a dramatic effect on the moon’s ice.

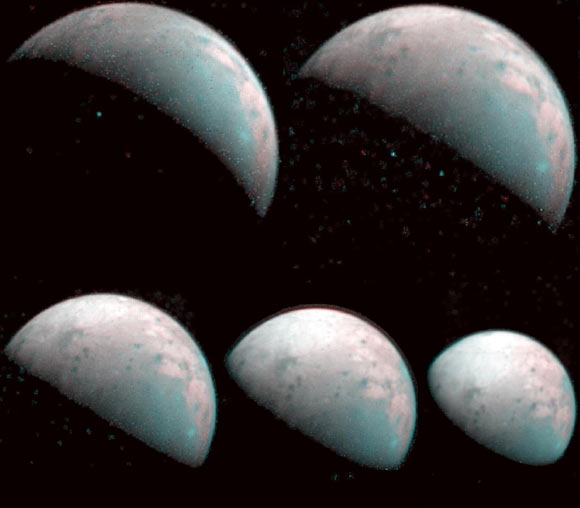

These five infrared images from the JIRAM instrument aboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft provide the first infrared mapping of Ganymede’s northern frontier. The images were taken every 20 minutes, beginning at time of closest approach (far left) on December 26, 2019, when the orbiter was about 62,000 miles (100,000 km) from Ganymede. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / SwRI / ASI / INAF / JIRAM.

“The JIRAM data show the ice at and surrounding Ganymede’s north pole has been modified by the precipitation of plasma,” said Juno co-investigator Dr. Alessandro Mura, a researcher at the National Institute for Astrophysics.

“It is a phenomenon that we have been able to learn about for the first time with Juno because we are able to see the north pole in its entirety.”

According to the Juno scientists, the water ice near Ganymede’s poles is amorphous.

This is because charged particles follow the moon’s magnetic field lines to the poles, where they impact, wreaking havoc on the ice there, preventing it from having a crystalline structure.

In fact, frozen water molecules detected at both poles have no appreciable order to their arrangement, and the amorphous ice has a different infrared signature than the crystalline ice found at Ganymede’s equator.

“These data are another example of the great science Juno is capable of when observing the moons of Jupiter,” said JIRAM program manager Dr. Giuseppe Sindoni, a scientist at the Italian Space Agency.

_____

This article is based on a press-release provided by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.