The crash of the ExoMars Schiaparelli test lander, also known as Entry, descent, and landing Demonstrator Module (EDM), last month was caused by a sensor malfunction, experts at the European Space Agency (ESA) said Wednesday.

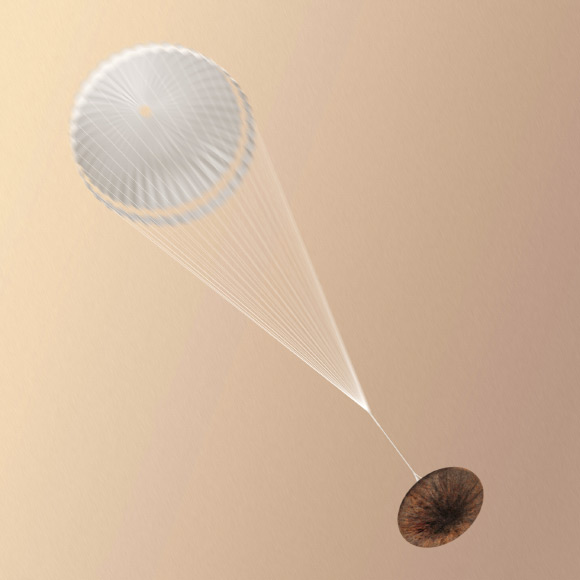

Artist’s impression of the Schiaparelli lander after the parachute has been deployed. Image credit: ESA / ATG Medialab.

Schiaparelli entered the Martian atmosphere at 10:42 a.m. EDT (7:42 a.m. PDT) on October 19, 2016, for its 6-min descent to the surface.

The entry of the module and associated braking occurred exactly as expected.

The parachute deployed normally at an altitude of 7.5 miles (12 km) and a speed of 1,075 mph (1,730 km/h).

The vehicle’s heatshield, having served its purpose, was released at an altitude of 4.8 miles (7.8 km).

As the lander descended under its parachute, its radar Doppler altimeter functioned correctly and the measurements were included in the guidance, navigation and control system.

However, saturation — maximum measurement — of the Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) had occurred shortly after the parachute deployment.

The IMU measures the rotation rates of the vehicle. Its output was generally as predicted except for this event, which persisted for about one second — longer than would be expected.

When merged into the navigation system, the erroneous information generated an estimated altitude that was negative — that is, below ground level.

This in turn successively triggered a premature release of the parachute and the backshell, a brief firing of the braking thrusters and finally activation of the on-ground systems as if Schiaparelli had already landed.

In reality, the vehicle was still at an altitude of around 2.3 miles (3.7 km).

This behavior has been clearly reproduced in computer simulations of the control system’s response to the erroneous information.

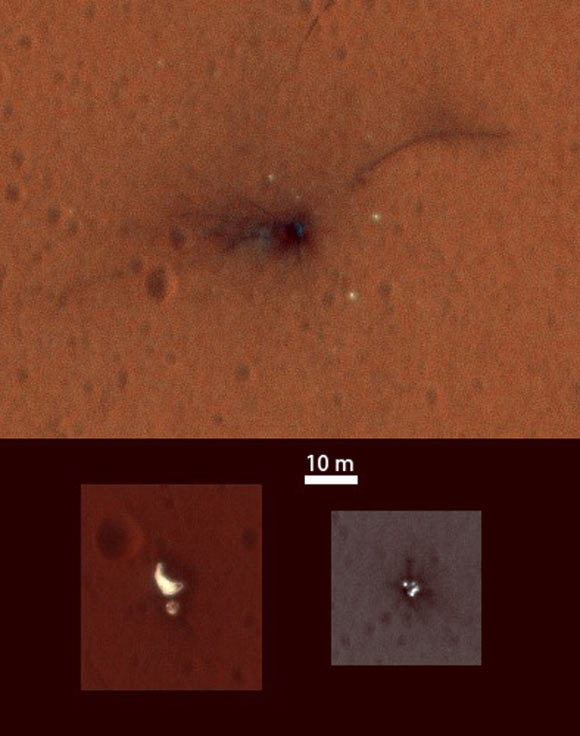

On November 1, HiRISE camera on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter observed the impact site of Schiaparelli lander, gaining the first color view of the site since the lander’s Oct. 19 arrival. These cutouts from the observation cover three locations where parts of Schiaparelli reached the ground: the lander module itself in the upper portion, the parachute and back shell at lower left, and the heat shield at lower right. The heat shield location was outside of the area covered in color. The scale bar of 32.8 feet (10 m) applies to all three cutouts. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona.

“This is still a very preliminary conclusion of our technical investigations,” said David Parker, ESA’s Director of Human Spaceflight and Robotic Exploration.

“The full picture will be provided in early 2017 by the future report of an external independent inquiry board, which is now being set up.”

“But we will have learned much from Schiaparelli that will directly contribute to the second ExoMars mission being developed with our international partners for launch in 2020.”

_____

This article is based on a press-release issued by the European Space Agency.