Cassini’s closest approach, within 295 miles (474 km) of Dione’s surface, will occur today, August 17. This flyby will be the fifth targeted encounter with the icy moon of the spacecraft’s tour at Saturn.

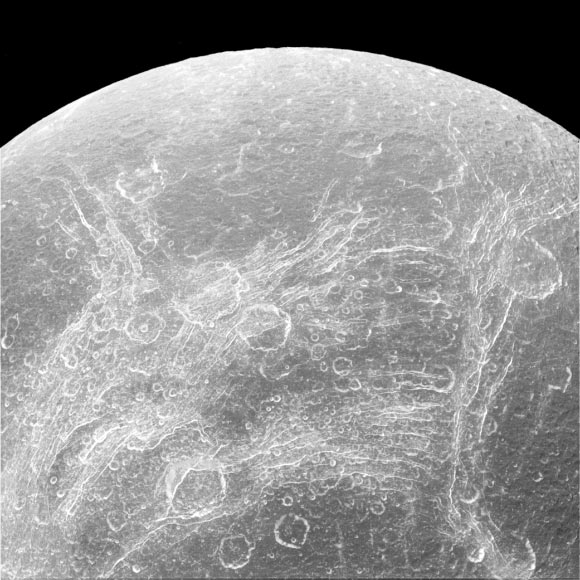

This image from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft shows a part of Dione’s surface that is covered by linear, curving features, called chasmata. The Voyager spacecrafts observed Dione in 1980 showing a complex surface structure, with wispy features on its trailing hemisphere. The nature of these features was unclear until 2004, when the Cassini spacecraft showed that they weren’t surface deposits of frost, as some had suspected, but rather a pattern of bright icy cliffs among myriad fractures. One possibility is that this stress pattern may be related to Dione’s orbital evolution and the effect of tidal stresses over time. This view looks toward the trailing hemisphere of Dione. Cassini obtained the image with its narrow-angle camera on April 11, 2015. The view was acquired at a distance of 68,000 miles (110,000 km) from Dione. North on Dione is up. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute.

“This will be our last chance to see Dione up close for many years to come,” said Dr Scott Edgington of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a scientist for the Cassini mission.

Cassini’s closest-ever flyby of Dione was in December 2011, at a distance of 60 miles (100 km).

Those previous close Cassini flybys yielded high-resolution views of the ‘wispy’ terrain on Dione first seen in 1980 during the Voyager mission. Cassini’s sharp views revealed the features to be the bright ice cliffs created by tectonic fractures.

During the August 17 flyby, Cassini’s cameras and spectrometers will get a high-resolution peek at Dione’s north pole at a resolution of only a few feet.

In addition, the mission’s Composite Infrared Spectrometer instrument will map areas on the moon that have unusual thermal anomalies. Meanwhile, Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer continues its search for dust particles emitted from Dione.

“Dione has been an enigma, giving hints of active geologic processes, including a transient atmosphere and evidence of ice volcanoes. But we’ve never found the smoking gun. The fifth flyby of Dione will be our last chance,” said Cassini science team member Dr Bonnie Buratti, also from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

After a series of close moon flybys in late 2015, Cassini will depart Saturn’s equatorial plane – where moon flybys occur most frequently – to begin a year-long setup of the mission’s daring final year.

For its grand finale, the spacecraft will repeatedly dive through the space between Saturn and its rings.