Rosetta mission scientists have announced the first results from the COmetary Secondary Ion Mass Analyser (COSIMA), one of Rosetta’s three dust analysis experiments.

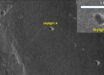

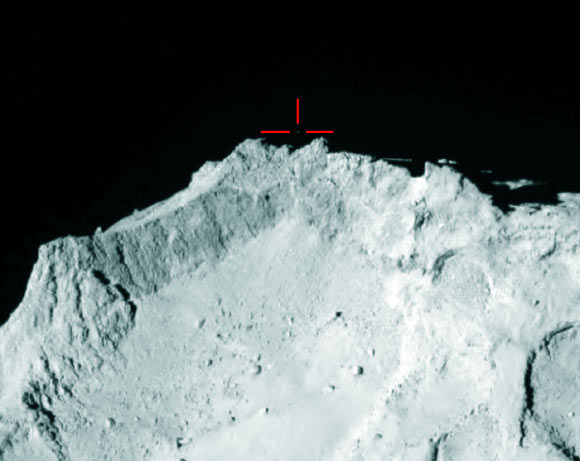

OSIRIS instrument on the Rosetta spacecraft captured this image of Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko on November 12, 2014; marked is what Rosetta scientists believe to be the Philae lander above the rim of the large depression – named Hatmehit – on the comet’s small lobe. Image credit: ESA / Rosetta / MPS for OSIRIS team / UPD / LAM / IAA / SSO / INTA / UPM / DASP / IDA.

The researchers looked at the way that many large dust grains broke apart when they were collected on the COSIMA’s target plate, typically at low speeds of 1–10 m/s.

The grains, which were originally at least 0.05 mm across, fragmented or shattered upon collection.

The fact that they broke apart so easily means that the individual parts were not well bound together. Moreover, if they had contained ice, they would not have shattered.

Instead, the icy component would have evaporated off the grain shortly after touching the collecting plate, leaving voids in what remained.

By comparison, if a pure water-ice grain had struck the detector, then only a dark patch would have been seen.

The dust grains were found to be rich in sodium, sharing the characteristics of interplanetary dust particles.

“We found that the dust particles released first when the comet started to become active again are fluffy (with porosity over 50 per cent). They don’t contain ice, but they do contain a lot of sodium,” said Dr Rita Schulz of ESA’s Scientific Support Office, who is the first author of a paper published in the journal Nature.

“We have found the parent material of interplanetary dust particles,” she added.

Dr Schulz and her colleagues believe that the particles detected were stranded on the comet’s surface after its last perihelion passage, when the flow of gas away from the surface had subsided and was no longer sufficient to lift dust grains from the surface.

While the dust was confined to the surface of 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, the gas continued evaporating at a very low level, coming from ever deeper below the surface during the years that the comet traveled furthest from the Sun.

Effectively, the comet nucleus was ‘drying out’ on the surface and just below it.

The scientists believe that fluffy dust particles collected by COSIMA originated from the dusty layer built up on the comet’s surface since its last close approach to the Sun.

“This layer is being removed as the activity of the comet is increasing again. We see this layer being removed, and we expect it to evolve into a more ice-rich phase in the coming months,” said Dr Martin Hilchenbach, COSIMA principal investigator and a co-author of the Nature paper.

“Rosetta’s dust observations close to the comet nucleus are crucial in helping us to link together what is happening at the very small scale with what we see at much larger scales, as dust is lost into the comet’s coma and tail. For these observations, it really is a case of watch this space as we continue to watch in real time how the comet evolves as it approaches the Sun along its orbit over the coming months,” said Dr Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist.

Rosetta scientists last week also released an image they say hints at where ESA’s Philae probe landed on 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

_____

Rita Schulz et al. Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko sheds dust coat accumulated over the past four years. Nature, published online January 26, 2015; doi: 10.1038/nature14159