The formation of giant planets has traditionally been divided into two pathways: core accretion and gravitational instability. However, in recent years, gravitational instability has become less favored, primarily due to the scarcity of observations of fragmented protoplanetary disks around young stars and the low occurrence rate of massive planets on very wide orbits. Astronomers using ESO’s Very Large Telescope and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array have now spotted large dusty clumps — close to the young star V960 Mon — that could collapse to create giant planets. They suggest this observation is the first evidence of gravitational instability occurring on planetary scales.

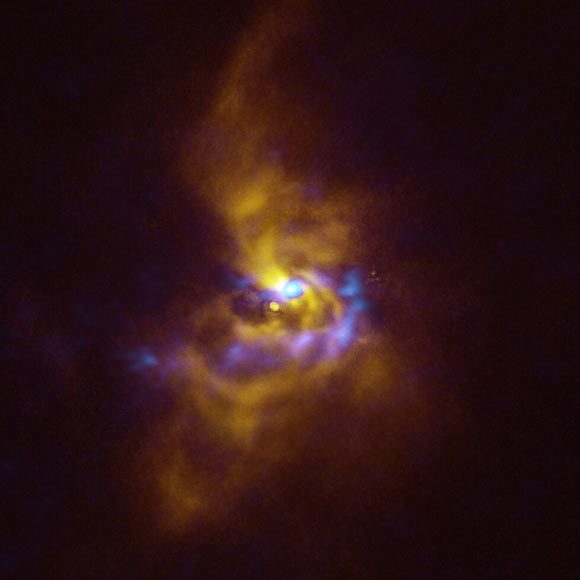

This composite image shows V960 Mon, a young star located over 5,000 light-years away in the constellation of Monoceros. Observations obtained using the Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch (SPHERE) instrument on ESO’s VLT, represented in yellow in this image, show that the dusty material orbiting V960 Mon is assembling together in a series of intricate spiral arms extending to distances greater than the entire Solar System. Meanwhile, the blue regions represent data obtained with ALMA. The ALMA data peers deeper into the structure of the spiral arms, revealing large dusty clumps that could contract and collapse to form giant planets roughly the size of Jupiter via a process known as gravitational instability. Image credit: ESO / ALMA / NAOJ / NRAO / Weber et al.

V960 Mon is located over 5,000 light-years away from Earth in the constellation of Monoceros.

Also known as 2MASS J06593158-0405277, this star attracted astronomers’ attention when it suddenly increased its brightness more than twenty times in 2014.

Further observations with the Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch (SPHERE) instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) revealed that the material orbiting V960 Mon is assembling together in a series of intricate spiral arms extending over distances bigger than the entire Solar System.

The finding motivated astronomers to analyze archival observations of the V960 Mon system made with ALMA.

The VLT observations probe the surface of the dusty material around the star, while ALMA can peer deeper into its structure.

“With ALMA, it became apparent that the spiral arms are undergoing fragmentation, resulting in the formation of clumps with masses akin to those of planets,” said Dr. Alice Zurlo, an astronomer at the Universidad Diego Portales.

Astronomers believe that giant planets form either by core accretion, when dust grains come together, or by gravitational instability, when large fragments of the material around a star contract and collapse.

While they have previously found evidence for the first of these scenarios, support for the latter has been scant.

“No one had ever seen a real observation of gravitational instability happening at planetary scales — until now,” said Dr. Philipp Weber, an astronomer at the University of Santiago, Chile.

“We’ve been searching for signs of how planets form for over ten years, and we couldn’t be more thrilled about this incredible discovery,” added Dr. Sebastián Pérez, also from the University of Santiago, Chile.

“ESO’s future Extremely Large Telescope will enable the exploration of the chemical complexity surrounding these clumps, helping us find out more about the composition of the material from which potential planets are forming,” Dr. Weber said.

The team’s paper appears in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

_____

Philipp Weber et al. 2023. Spirals and Clumps in V960 Mon: Signs of Planet Formation via Gravitational Instability around an FU Ori Star? ApJL 952, L17; doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/ace186