Non-tailed double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses infect bacteria and dominate water samples from the world’s oceans. They have long escaped analysis because they have characteristics that standard tests can’t detect. However, scientists from MIT and elsewhere have now managed to isolate and study representatives of these elusive viruses.

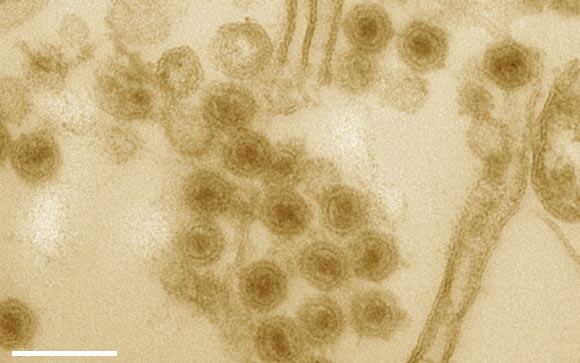

Thin-section electron microscopy of an agar overlay containing plaques of the representative Autolykiviridae virus 1.008.O; virus particles in contact with cell membranes are observed to occasionally possess tail-tube-like structures, whereas those not in contact with cells do not. Image credit: Kauffman et al, doi: 10.1038/nature25474.

The newly identified viruses lack the ‘tail’ found on most catalogued and sequenced bacterial viruses, and have several other unusual properties that have led to their being missed by previous studies.

To honor that fact, MIT postdoc Kathryn Kauffman and co-authors named this new group the Autolykiviridae — after a character from Greek mythology who was storied for being difficult to catch.

And, unlike typical viruses that prey on just one or two types of bacteria, these tailless varieties can infect dozens of different types, often of different species, underscoring their ecological relevance.

“Current environmental models of virus-bacteria interactions are based on the well-studied tailed dsDNA viruses, so they may be missing important aspects of the interactions taking place in nature,” Kauffman said.

“While most of the viruses studied in labs have tails, most of those in the ocean don’t,” said MIT Professor Martin Polz.

So the researchers decided to study one subset of non-tailed dsDNA viruses, which infects a group of bacteria called Vibrio.

After extensive tests, they found that some of these were infecting unusually large numbers of hosts.

“After sequencing representatives of the Autolykiviridae, we found their genomes were quite different from other viruses,” Professor Polz said.

“For one thing, their genomes are very short: about 10,000 bases, compared to the typical 40,000-50,000 for tailed viruses. When we found that, we were surprised.”

With the new sequence information, the scientists were able to comb through databases and found that such viruses exist in many places.

The research also showed that these viruses tend to be underrepresented in databases because of the ways samples are typically handled in labs.

The methods the team developed to obtain these viruses from environmental samples could help scientists avoid such losses of information in the future.

In addition, typically the way researchers test for viral activity is by infecting bacteria with the viral sample and then checking the samples a day later to look for signs that patches of the bacteria have been killed off. But these particular non-tailed viruses often act more slowly, and the killed-off regions don’t show up until several days have passed — so their presence was never noticed in most studies.

“We don’t think it’s ocean-specific at all. For example, the viruses may even be prevalent in the human biome, and they may play roles in major biogeochemical cycles, he says, such as the cycling of carbon,” Professor Polz said.

Another important aspect of theses findings is that the Autolykiviridae were shown to be members of an ancient viral lineage that is defined by specific types of capsids, the protein shell encasing the viral DNA.

Though this lineage is known to be very diverse in animals and protists — and includes viruses such as the adenoviruses that infect humans, and the giant viruses that infect algae — very few viruses of this kind have been found to infect bacteria.

“This work substantially changes the existing ideas on the composition of the ocean virome by showing that the content of small, non-tailed viruses — is comparable to that of the tailed viruses — that are currently thought to dominate the virosphere,” said National Institutes of Health researcher Dr. Eugene Koonin, who was not involved in this research.

“This work is important also for understanding the evolution of the virus world because it shows that viruses related to the most common viruses of eukaryotes (such as adenoviruses, poxviruses, and others), at least in terms of the capsid structure, are much wider-spread in prokaryotes than previously suspected.”

Details of the research are published in the journal Nature.

_____

Kathryn M. Kauffman et al. A major lineage of non-tailed dsDNA viruses as unrecognized killers of marine bacteria. Nature, published online January 24, 2018; doi: 10.1038/nature25474