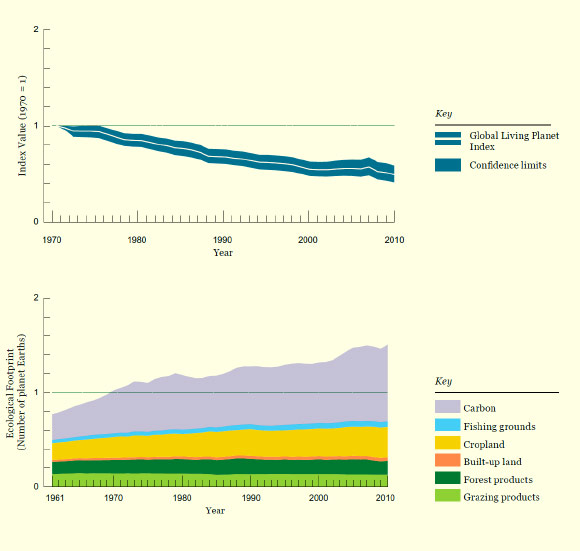

According to WWF’s Living Planet Report 2014, global wildlife populations have declined by 52 per cent in 40 years.

Global wildlife populations have declined by more than half in just 40 years as measured in the Living Planet Report 2014.

The Living Planet Report 2014 is the 10th edition of WWF’s biennial flagship publication.

The report tracks over 10,000 vertebrate species populations from 1970 to 2010 through the Living Planet Index.

This year’s Living Planet Index features updated methodology that more accurately tracks global biodiversity and provides a clearer picture of the health of our natural environment. While the findings reveal that the state of the world’s species is worse than in previous reports, the results also put finer focus on available solutions.

According to the report, populations of fish, birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles have declined by an average of 52 per cent since 1970.

Terrestrial species declined by 39 per cent between 1970 and 2010, a trend that shows no sign of slowing down. The loss of habitat to make way for human land use continues to be a major threat, compounded by hunting.

Freshwater species have suffered a 76 per cent decline, an average loss almost double that of land and marine species. The main threats to freshwater species are habitat loss and fragmentation, pollution and invasive species.

Marine species declined 39 per cent between 1970 and 2010. The period from 1970 through to the mid-1980s experienced the steepest decline, after which there was some stability, before another recent period of decline. The steepest declines can be seen in the tropics and the Southern Ocean – species in decline include marine turtles, many sharks, and large migratory seabirds like the wandering albatross.

Biodiversity is declining in both temperate and tropical regions, but the decline is greater in the tropics. The 6,569 populations of 1,606 species in the temperate Living Planet Index declined by 36 per cent from 1970 to 2010. The tropical Living Planet Index shows a 56 per cent reduction in 3,811 populations of 1,638 species over the same period. Latin America shows the most dramatic decline – a fall of 83 per cent.

While biodiversity loss around the world is at critical levels, the report highlights how effectively managed protected areas can support wildlife.

In one example, Nepal is noted for increasing its tiger population in recent years.

Another example comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC): “only around 880 mountain gorillas remain in the wild – about 200 of them in DRC’s Virunga National Park. Although they remain critically endangered, they are the only species of great ape whose numbers are increasing, thanks to intensive conservation efforts.”

Overall, populations in land-based protected areas suffer less than half the rate of decline of those in unprotected areas.

“The scale of biodiversity loss and damage to the very ecosystems that are essential to our existence is alarming. This damage is not inevitable but a consequence of the way we choose to live. Although the report shows the situation is critical, there is still hope,” said Prof Ken Norris, Director of Science at the Zoological Society of London.

“Protecting nature needs focused conservation action, political will and support from businesses.”

The report also shows Ecological Footprint – a measure of humanity’s demands on nature – continuing its upward climb.

According to the report, humanity’s demand on the planet is more than 50 per cent larger than what nature can renew. It would take 1.5 Earths to produce the resources necessary to support our current Ecological Footprint.

This global overshoot means, for example, that we are cutting timber more quickly than trees regrow, pumping freshwater faster than groundwater restocks, and releasing CO2 faster than nature can sequester it.

Delinking the relationship between footprint and development is a key global priority indicated in the report.

While per capita Ecological Footprint of high-income countries is five times that of low-income countries, research demonstrates that it is possible to increase living standards while restraining resource use.

The ten countries with the largest per capita Ecological Footprints are: Kuwait, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Denmark, Belgium, Trinidad and Tobago, Singapore, United States of America, Bahrain and Sweden.

“Ecological overshoot is the defining challenge of the 21st century. Nearly three-quarters of the world’s population lives in countries struggling with both ecological deficits and low incomes. Resource restraints demand that we focus on how to improve human welfare by a means other than sheer growth,” said Dr Mathis Wackernagel, President and Co-founder of Global Footprint Network.

While there are many hard facts about the state of our planet in the report, there are grounds for optimism. We have an opportunity to make decisions that allow all people to live a good life on a healthy planet, in harmony with nature.

In 2015, world leaders will agree two potentially critical global agreements: the post-2015 development framework – which will include Sustainable Development Goals to be achieved by all countries by 2030; and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.