A team of scientists at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute), Australia, was able to test blood samples at four different time points in an otherwise healthy 47-year-old woman, who presented with COVID-19 and had mild-to-moderate symptoms requiring hospital admission.

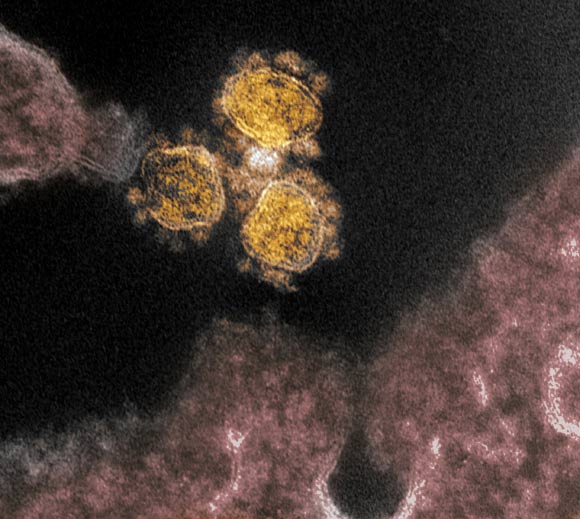

This transmission electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 virus isolated from a patient in the U.S. Virus particles (round gold objects) are shown emerging from the surface of cells cultured in the lab. The spikes on the outer edge of the virus particles give coronaviruses their name, crown-like. Image credit: NIAID-RML.

A 47-year-old woman from Wuhan, Hubei province, China, presented to an emergency department in Melbourne, Australia. Her symptoms commenced 4 days earlier with lethargy, sore throat, dry cough, pleuritic chest pain, mild dyspnea and subjective fevers.

She traveled from Wuhan to Australia 11 days before presentation and had no contact with the Huanan seafood market or with known COVID-19 cases. She was otherwise healthy and was a non-smoker taking no medications.

Clinical examination revealed a temperature of 38.5 degrees Celsius, a pulse rate of 120 beats per minute, a blood pressure of 140/80 mm Hg, a respiratory rate of 22 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 98% while breathing ambient air. Lung auscultation revealed bi-basal rhonchi.

“We looked at the whole breadth of the immune response in this patient using the knowledge we have built over many years of looking at immune responses in patients hospitalised with influenza,” said Doherty Institute’s Dr. Oanh Nguyen, co-author of the study.

“Three days after the patient was admitted, we saw large populations of several immune cells, which are often a tell-tale sign of recovery during seasonal influenza infection, so we predicted that the patient would recover in three days, which is what happened.”

The researchers were able to do this research so rapidly thanks to SETREP-ID (Sentinel Travellers and Research Preparedness for Emerging Infectious Disease), a platform that enables a broad range of biological sampling to take place in returned travelers in the event of a new and unexpected infectious disease outbreak, which is exactly how COVID-19 started in Australia.

“When COVID-19 emerged, we already had ethics and protocols in place so we could rapidly start looking at the virus and immune system in great detail,” said Doherty Institute’s Dr. Irani Thevarajan, first author of the study.

“Already established at a number of Melbourne hospitals, we now plan to roll out SETREP-ID as a national study.”

The team was able to dissect the immune response leading to successful recovery from COVID-19, which might be the secret to finding an effective vaccine.

“We showed that even though COVID-19 is caused by a new virus, in an otherwise healthy person, a robust immune response across different cell types was associated with clinical recovery, similar to what we see in influenza,” said Doherty Institute’s Professor Katherine Kedzierska, senior author of the study.

“This is an incredible step forward in understanding what drives recovery of COVID-19. People can use our methods to understand the immune responses in larger COVID-19 cohorts, and also understand what’s lacking in those who have fatal outcomes.”

“Current estimates show more than 80% of COVID-19 cases are mild-to-moderate, and understanding the immune response in these mild cases is very important research,” Dr. Thevarajan said.

“We hope to now expand our work nationally and internationally to understand why some people die from COVID-19, and build further knowledge to assist in the rapid response of COVID-19 and future emerging viruses.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Medicine.

_____

I. Thevarajan et al. Breadth of concomitant immune responses prior to patient recovery: a case report of non-severe COVID-19. Nat Med, published online March 16, 2020; doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0819-2

This article is based on text provided the University of Melbourne.