Researchers have for the first time demonstrated that gravity plays a role in the formation of molecular aggregates, and that it can even be used to make them right-handed or left-handed.

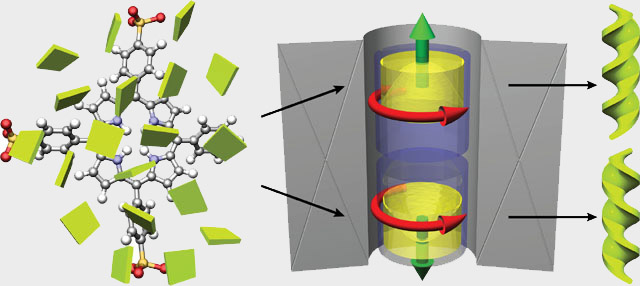

Non-chiral porphyrins, shown with green blocks, can form screw-shaped chiral structures. The rotation (red arrows) and gravity (green arrows) determine whether left- or right-handed screw structures are formed (N. Micali et al)

Many chemical and biochemical substances exist in the form of one of two structures that are the exact mirror-image of one another. However, no one could explain exactly how these images originally formed.

Now, researchers from the Nijmegen High Field Magnet Laboratory (HFML), the Netherlands, the CNR-IPCF Institute in Messina, Italy, and the University of Messina, have demonstrated that a combination of gravitational and rotational forces may play a role. The findings are published in Nature Chemistry.

The team carried out a growth experiment in which flat dye molecules (porphyrins) were allowed to aggregate. By varying the gravitational force using a strong magnetic field, and by rotating the vials containing the molecules in solution, the researchers were able to produce left-handed or right-handed aggregates as desired. The aggregates look a little like screws – or their mirror image.

The super magnets at HFML are so strong that they can cause non-magnetic materials to levitate. It is also possible to invert the gravitational force, as the magnetic force varies in strength at different places within the magnet – a property that the researchers made use of, placing a whole series of vials in the magnet.

Therefore in one vial the gravitational force was normal, in another higher than normal, and there were other vials in which the gravitational force was less than normal or even inverted. All vials were rotated clockwise in exactly the same manner – only where the gravitational force was inverted was the rotation reversed compared with the gravitational force, and therefore anti-clockwise.

The screws created all wound in the direction in which the liquid had moved in relation to the gravitational field.

The team is now trying to work out the exact mechanism behind this discovery. This is important because the researchers believe that they can also produce other types of chiral structures on demand in their magnet.

![Chemical structure of the cyclo[48]carbon [4]catenan. Image credit: Harry Anderson.](https://cdn.sci.news/images/2025/08/image_14141-Cyclo-48-Carbon-104x75.jpg)