A new genus and species of desmostylian mammal that lived about 23 million years ago (early Miocene) has been identified from fossils found on Unalaska, an island in the Fox Islands group of the Aleutian Islands in the U.S. state of Alaska.

The newly-discovered creature belongs to the order Desmostylia, a group of extinct marine mammals whose closest living relatives are elephants, sea cows and manatees.

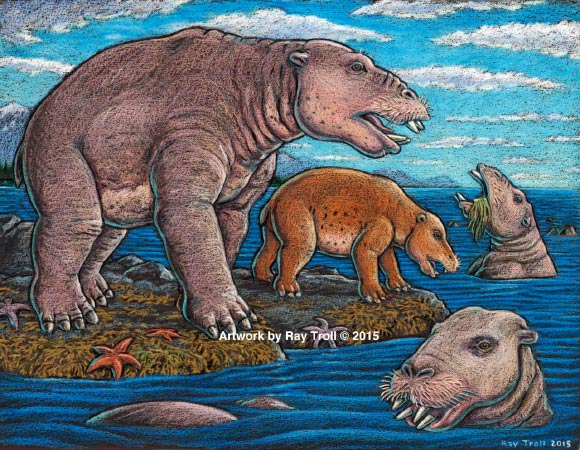

Desmostylian mammals were large-bodied herbivores with enhanced adaptations for life in water and bulk aquatic feeding.

They lived around the margins of the North Pacific Ocean from the Oligocene until the end of the Miocene, 32.5 to 10.5 million years ago.

Unlike whales and seals, but like manatees, they were vegetarians. They rooted around coastlines, ripping up vegetation, such as marine algae, sea grass and other near-shore plants.

They probably swam like polar bears, using their strong front limbs to power along, and walked on land a bit, lumbering like a sloth.

The new desmostylian genus and species was named Ounalashkastylus tomidai by a team of paleontologists from Japan, Canada and the United States.

“Ounalashka means ‘near the peninsula’ in the Aleut language of the indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands. Stylus is from the Latin for ‘column’ and refers to the shape of cusps in the teeth,” explained team member Prof. Louis Jacob of Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

“Tomida honors distinguished Japanese vertebrate paleontologist Yukimitsu Tomida.”

A detailed description of Ounalashkastylus tomidai appears in the special issue of the Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology.

The extinct mammal had a long snout and tusks. It also possessed a unique tooth and jaw structure that indicates it was not only a vegetarian, but literally sucked vegetation from shorelines like a vacuum cleaner.

“The new animal made us realize that desmostylians do not chew like any other animal. They clench their teeth, root up plants and suck them in,” Prof. Jacob said.

“To eat, the animals buttressed their lower jaw with their teeth against the upper jaw, and used the powerful muscles that attached there, along with the shape of the roof of their mouth, to suction-feed vegetation from coastal bottoms.”

“Big muscles in the neck would help to power their tusks, and big muscles in the throat would help with suction.

He added: “no other mammal eats like that. The enamel rings on the teeth show wear and polish, but they don’t reveal consistent patterns related to habitual chewing motions.”

This artwork shows the desmostylian mammal Neoparadoxia cecilialina. Image credit: Doyle V. Trankina.

The Unalaska fossils represent at least four individuals, and one is a baby.

“The baby tells us they had a breeding population up there. They must have stayed in sheltered areas to protect the young from surf and currents,” Prof. Jacobs said.

“In addition, the baby also tells us that this area along the Alaska coast was biologically productive enough to make it a good place for raising a family,” said co-author Dr Anthony Fiorillo of the Perot Museum of Nature and Science and Southern Methodist University.

The discovery of Ounalashkastylus tomidai indicates the desmostylian group was larger and more diverse than previously known.

_____

Kentaro Chiba et al. 2016. A new desmostylian mammal from Unalaska (USA) and the robust Sanjussen jaw from Hokkaido (Japan), with comments on feeding in derived desmostylids. Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology, vol. 28, no. 1-2; doi: 10.1080/08912963.2015.1046718