Using remote sensing techniques and geophysical surveys, archaeologists from the Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project have discovered the remains of a major new prehistoric stone monument hidden beneath the bank of the Durrington Walls ‘super-henge,’ less than 2 miles (3 km) from better-known Stonehenge.

The Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project team has revealed traces of up to 100 standing stones beneath Durrington Walls super-henge. The stones were up to 15 feet (4.5 m) in height, and are believed to have been deliberately toppled over the south-eastern edge of the bank of the circular enclosure before being incorporated into it. Image credit: Juan Torrejon Valdelomar / Joachim Brandtner / LBI ArchPro.

Durrington Walls is one of the largest known henge monuments measuring 1,640 feet (500 m) in diameter and thought to have been built around 4,500 years ago.

Measuring more than 4,900 feet (1.5 km) in circumference, it is surrounded by a ditch up to 58 feet (17.6 m) wide and an outer bank 131 feet (40 m) wide and surviving up to a height of 3.3 feet (1 m).

The henge surrounds several smaller enclosures and timber circles and is associated with a recently excavated later Neolithic settlement.

The Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project team has now discovered evidence for a row of up to 100 standing stones, some of which may have originally measured up to 15 feet (4.5 m) in height. Many of these stones have survived because they were pushed over and the massive bank of the later henge raised over the recumbent stones or the pits in which they stood.

“Our high resolution ground penetrating radar data has revealed an amazing row of up to 100 standing stones a number of which have survived after being pushed over and a massive bank placed over the stones,” said team member Prof Wolfgang Neubauer of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology.

“In the east up to 30 stones, measuring up to size of 15 x 5 x 3.3 feet (4.5 x 1.5 x 1 m), have survived below the bank whereas elsewhere the stones are fragmentary or represented by massive foundation pit.”

“We don’t think there’s anything quite like this anywhere else in the world. This is completely new and the scale is extraordinary,” said team member Prof Vince Gaffney from the University of Bradford.

“The presence of what appear to be stones, surrounding the site of one of the largest Neolithic settlements in Europe adds a whole new chapter to the Stonehenge story,” said Dr Nick Snashall, National Trust Archaeologist for the Avebury and Stonehenge World Heritage Site.

At Durrington, more than 4,500 years ago, a natural depression near the river Avon appears to have been accentuated by a chalk cut scarp and then delineated on the southern side by the row of massive stones.

Essentially forming a C-shaped arena, the monument may have surrounded traces of springs and a dry valley leading from there into the Avon.

The earthwork enclosure at Durrington Walls was built about a century after the Stonehenge sarsen circle (c. 2,700 BC), but the new stone row could well be contemporary with or earlier than this.

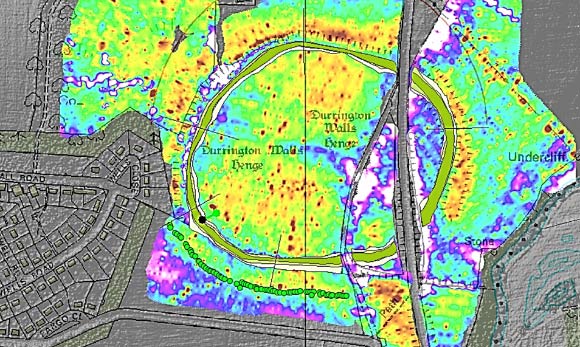

Electromagnetic and LIDAR data, overlain by green circles marking the stone row. Image credit: University of Bradford / Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project.

Not only does this new evidence demonstrate an early phase of monumental architecture at one of the greatest ceremonial sites in prehistoric Europe, it also raises significant questions about the landscape the builders of Stonehenge inhabited and how they changed this with new monument-building during the 3rd millennium BC.

“Our understanding of Stonehenge and the Stonehenge landscape has been built up gradually over three centuries of archaeological fieldwork, but the Hidden Landscapes Project marks a radical transformation not only in terms of our knowledge base but also our capacity to explore further,” said Paul Garwood from the University of Birmingham.

“The results of our project, especially high-resolution mapping of almost the entire landscape, will provide the basis for future research in the Stonehenge landscape for generations to come. The sheer scale, detail and seamless character of the map data, new site discoveries, and our reinterpretations of every facet of past activity around Stonehenge, sets new agendas for Stonehenge research and for landscape archaeology more widely.”

“This discovery of a major new stone monument, which has been preserved to a remarkable extent, has significant implications for our understanding of Stonehenge and its landscape setting,” Prof Gaffney said.