The culture that thrived at Teotihuacan in the Classic period has a unique place in Mesoamerican history. Today, it is held as an emblem of the Mexican national past and is one of the most visited archaeological sites in the Americas. Nevertheless, curious visitors are told that the ethnic and linguistic affiliation of the Teotihuacanos remains unknown. Whereas the decipherment of other Mesoamerican writing systems has provided a wealth of information about dynasties and historical events, scholars have not been able to access information about Teotihuacan society from their own written sources. Indeed, the topic of writing at Teotihuacan prompts several contentious questions. Do signs in Teotihuacan imagery constitute writing? If it is writing, how did it work? Was it meant to be read independently of language? If it did represent a specific language, then what language was it? University of Copenhagen researchers Magnus Pharao Hansen and Christopher Helmke propose that Teotihuacan writing shared basic principles with other Mesoamerican scribal traditions, including the use of logograms according to the rebus principle, as well as a principle they term ‘double spelling.’ Arguing that it did encode a specific and identifiable language, namely, a Uto-Aztecan language immediately ancestral to Nahuatl, Cora, and Huichol, they offer new readings of several Teotihuacan glyphs.

A view over the smaller pyramids on the eastern side of Plaza de la Luna from Piramide de la Luna towards Piramide del Sol at Teotihuacan. Image credit: Daniel Case / CC BY-SA 3.0.

Teotihuacan is a sacred pre-Columbian city that was founded around 100 BCE and flourished until 600 CE.

Located in the northeast of the Basin of Mexico, the ancient city covered 20 square km, supported a population of up to 125,000 residents, and was in touch with other Mesoamerican civilizations.

It is unclear who the builders of Teotihuacan were, and what relation they had to the peoples which followed. It is also unclear why the city was abandoned. There are several theories which include foreign invasion, a civil war, an ecological catastrophe, or some combination of all three.

“There are many different cultures in Mexico. Some of them can be linked to specific archaeological cultures. But others are more uncertain. Teotihuacan is one of those places,” Dr. Pharao Hansen said.

“We don’t know what language they spoke or what later cultures they were linked to.”

“A trained eye can easily distinguish Teotihuacan culture from other contemporary cultures,” Dr. Helmke added.

“For example, the ruins in Teotihuacan show that parts of the city were inhabited by the Maya — a civilization that is much better known today than Teotihuacan.”

The ancient people of Teotihuacan left behind a series of signs, mainly as murals and decorated pottery.

For years, researchers have debated whether these signs even constitute an actual written language.

The authors show that the writing on the walls of Teotihuacan is in fact record a language that is a linguistic ancestor of the Cora and Huichol languages and the Aztec language Nahuatl.

The Aztecs are another famous culture from Mexico. Until now, it was believed that the Aztecs migrated to central Mexico after the fall of Teotihuacan.

However, the researchers point to a linguistic connection between Teotihuacan and the Aztec, which could indicate that Nahuatl-speaking populations arrived to the area much earlier and that they are actually direct descendants of the inhabitants of Teotihuacan.

In order to identify the linguistic similarities between the language of Teotihuacan and other Mesoamerican languages, the scientists had to reconstruct a much earlier version of Nahuatl.

“Otherwise, it would be a bit like trying to decipher the runes on the famous Danish runestones, such as the Jelling Stone, using modern Danish. That would be anachronistic. You have to try to read the text using a language that is closer in time and contemporary,” Dr. Helmke said.

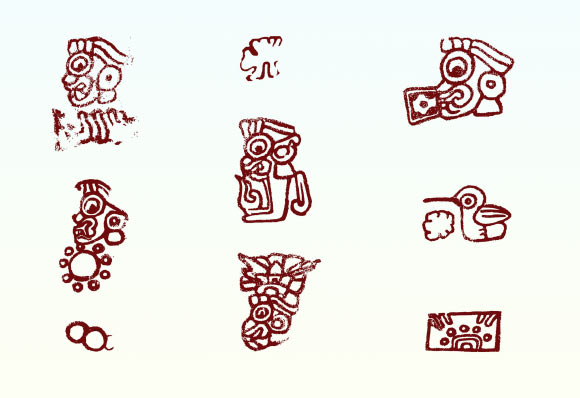

Examples of logograms that make up the Teotihuacan written language. Image credit: Christophe Helmke, University of Copenhagen.

The Teotihuacan written language is difficult to decipher for several reasons.

One reason is that the logograms that make up the script sometimes have a direct meaning, so that an image of a coyote, for example, should simply be understood to mean ‘coyote.’

Elsewhere in the text, the signs must be read as a kind of rebus, where the sounds of the objects depicted must be put together to form a word, which may be more conceptual and therefore difficult to write as a single figurative logogram.

This makes it crucial to have a good knowledge of both the Teotihuacan writing system and the Uto-Aztecan language, which these researchers believe is recorded in the texts.

It is necessary to know how the words sounded back then in order to solve the written puzzles of Teotihuacan.

That is why the authors are working on several fronts. They are simultaneously reconstructing the Uto-Aztecan language, a difficult task in itself, and using this ancient language to decipher the Teotihuacan texts.

“In Teotihuacan, you can still find pottery with text on it, and we know that more murals will turn up,” Dr. Pharao Hansen said.

“It is clearly a limitation to our research that we do not have more texts.”

“It would be great if we could find the same signs used in the same way in many more contexts.”

“That would further support our hypothesis, but for now we have to work with the texts we have.”

Dr. Pharao Hansen and Dr. Helmke are excited about their breakthrough.

“No one before us has used a language that fits the time period to decipher this written language,” Dr. Pharao Hansen said.

“Nor has anyone been able to prove that certain logograms had a phonetic value that could be used in contexts other than the logogram’s main meaning.”

“In this way, we have created a method that can serve as a baseline for others to build on in order to expand their understanding of the texts.”

The team’s paper was published in the journal Current Anthropology.

_____

Magnus Pharao Hansen & Christophe Helmke. 2025. The Language of Teotihuacan Writing. Current Anthropology 66 (5); doi: 10.1086/737863