The second half of the first millennium CE in Central and Eastern Europe was accompanied by fundamental cultural and political transformations. This period of change is commonly associated with the appearance of the Slavs, which is supported by textual evidence and coincides with the emergence of similar archaeological horizons. However, so far there has been no consensus on whether this archaeological horizon spread by migration, ‘Slavicization’ or a combination of both. The genetic data remain sparse, especially owing to the widespread practice of cremation in the early phase of the Slavic settlement. In new research, scientists sequenced genomes of 555 ancient individuals, including 359 samples from Slavic contexts from as early as the 7th century CE. The new data demonstrate large-scale population movement from Eastern Europe during the 6th to 8th centuries, replacing more than 80% of the local gene pool in Eastern Germany, Poland and Croatia.

Seal of Yaroslav the Wise, the Grand Prince of Kyiv from 1019 until 1054 and the father of Anna Yaroslavna, the Queen of France. Image credit: Sheremetievs Museum.

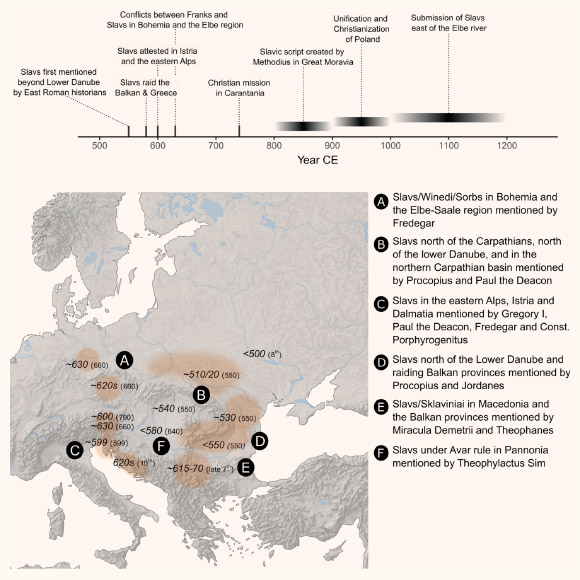

The term Slavs first appears as an ethnonym in the course of the 6th century in Constantinople and later in the West.

Written sources locate them initially north of the Lower Danube, and later in the Carpathian Basin, the Balkans and the Eastern Alps.

Many came under the rule of the Avar steppe empire along the Middle Danube (567 CE to around 800 CE).

In the 7th century, there is evidence for the presence of Slavs in much of East-Central and Southeastern Europe.

Where Slavs lived, Roman, Germanic and other pre-Slavic infrastructures were usually replaced by rather simple ways of life, archaeologically characterized by small settlements of pit houses, cremation burials, handmade, undecorated pottery and modest, low-metal material culture, known as the Prague-Korchak group.

More complex social systems and regional rulership developed later in the contact zones with Byzantium and the Christian West.

How Slavs Transformed Europe

The first comprehensive ancient DNA study of medieval Slavic populations shows that the rise of the Slavs was, at its core, a story of people on the move.

Their genetic signatures point to an origin in the region stretching from southern Belarus to central Ukraine — a geographic area that matches what many linguistic and archaeological reconstructions had long suggested.

“While direct evidence from early Slavic core regions is still rare, our genetic results offer the first concrete clues to the formation of Slavic ancestry — pointing to a likely origin somewhere between the Dniester and Don rivers,” said Dr. Joscha Gretzinger, a geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

In the study, Dr. Gretzinger and colleagues obtained genome-wide data from 555 unique ancient individuals from 26 different sites from Central and Eastern Europe, creating, in combination with previously published data, a dense sampling transect for three regions: (i) Elbe-Saale Region in Eastern Germany as the main study area, (ii) the Northwestern Balkans, and (iii) Poland-Northwestern Ukraine.

The new data show that, beginning in the 6th century CE, large-scale migrations carried the Eastern European ancestry across wide areas of Central and Eastern Europe, which caused the genetic makeup of regions like Eastern Germany and Poland to shift almost entirely.

Yet the expansion did not follow the model of conquest and empire: instead of sweeping armies and rigid hierarchies, the migrants built their new societies on flexible communities, often organized around extended families and patrilineal kinship ties.

Also, this was not a single, uniform model across all regions.

In Eastern Germany, the shift was profound: large, multi-generational pedigrees became the backbone of society, with kinship networks more extensive and structured than the small nuclear families seen in the preceding Migration Period.

In contrast, in areas such as Croatia, the arrival of Eastern European groups brought much less disruption to existing social patterns.

Here, social organization often retained many features of earlier periods, resulting in communities where new and old traditions blended or persisted side by side.

This regional diversity in social structure highlights how the spread of Slavic groups was not a one-size-fits-all process, but rather a dynamic transformation that adapted to local contexts and histories.

“Rather than a single people moving as one, the Slavic expansion was not a monolithic event but a mosaic of different groups, each adapting and blending in its own way — suggesting there was never just one ‘Slavic’ identity, but many,” said Dr. Zuzana Hofmanová, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and Masaryk University.

Historical overview of Slavs in Europe: the timeline lists major historical events associated with the Slavs in Central Europe; the map features schematized historical attestations for the appearance of Slavs (Sklavenoi – Slavi – Winedi); Italic numbers indicate the date of the attested event, with the respective report date in brackets. Image credit: Gretzinger et al., doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09437-6.

Eastern Germany

In Eastern Germany specifically, the genetic data show an especially striking story.

Following the decline of the Thuringian kingdom, more than 85% of the ancestry in the region can be attributed to new arrivals from the East.

This marks a shift from the earlier Migration period, when the population was a cosmopolitan mix as best illustrated by the site of Brücken.

With the spread of the Slavs, this diversity gave way to a population profile almost identical to modern Slavic-speaking groups in Eastern Europe.

These new communities organized themselves around large extended families and patrilineal descent — while women of marriageable age typically left their home villages to join new households elsewhere.

Notably, the genetic legacy of these early Eastern European settlers endures today among the Sorbs, a Slavic-speaking minority in Eastern Germany.

Despite centuries of surrounding cultural and linguistic change, the Sorbs have retained a genetic profile closely related to the early medieval Slavic populations that settled the region more than 1,000 years ago.

Poland

In Poland specifically, the research overturns earlier ideas of long-term population continuity.

Genetic results show that starting in the 6th and 7th centuries CE, the region’s earlier inhabitants — descendants of populations with strong links to Northern Europe and Scandinavia in particular — almost entirely disappeared and were successively replaced by newcomers from the East, who are closely related to modern Poles, Ukrainians, and Belarusians.

While the population shift was overwhelming, the genetic evidence also reveals minor traces of mixing with local populations.

These findings underscore both the scale of population change and the complex dynamics that shaped the roots of today’s Central and Eastern European linguistic landscape.

Croatia

The Northern Balkans specifically present a different pattern compared to the northern immigration area — a story of both change and continuity.

Ancient DNA from Croatia and neighboring regions reveals a significant influx of Eastern European-related ancestry, but not a complete genetic replacement.

Instead, Eastern European migrants mixed with the region’s diverse local populations, creating new, hybrid communities.

Genetic analyses indicate that in present-day Balkan populations, the proportion of this incoming Eastern European ancestry varies considerably but often makes up roughly half or even less of the modern gene pool, highlighting the region’s complex demographic history.

Here, the Slavic migration was not a wave of conquest but a long process of intermarriage and adaptation, resulting in the cultural, linguistic and genetic diversity that still characterizes the Balkan Peninsula today.

New Chapter in European History

Mostly where early Slavic groups are found in the archaeological and historical record, their genetic traces match: a common ancestral origin, but regional differences shaped by the degree of mixing with local populations.

In the north, earlier Germanic peoples had largely moved away, leaving room for Slavic settlement.

In the south, the Eastern European newcomers merged with established communities.

This patchwork process explains the remarkable diversity found in the cultures, languages, and even the genetics of today’s Central and Eastern Europe.

“The spread of the Slavs was likely the last demographic event of continental scale to permanently and fundamentally reshape both the genetic and linguistic landscape of Europe,” said Dr. Johannes Krause, director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

The findings were published September 3 in the journal Nature.

_____

J. Gretzinger et al. Ancient DNA connects large-scale migration with the spread of Slavs. Nature, published online September 3, 2025; doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09437-6

This article was adapted from an original release by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.