On March 11, 1437, Korean royal astronomers spotted a bright new star in the constellation Scorpius. From the ancient records, modern astronomers determined that what the Koreans saw was a classical nova explosion, but they had been unable to find the binary system that caused it — until now.

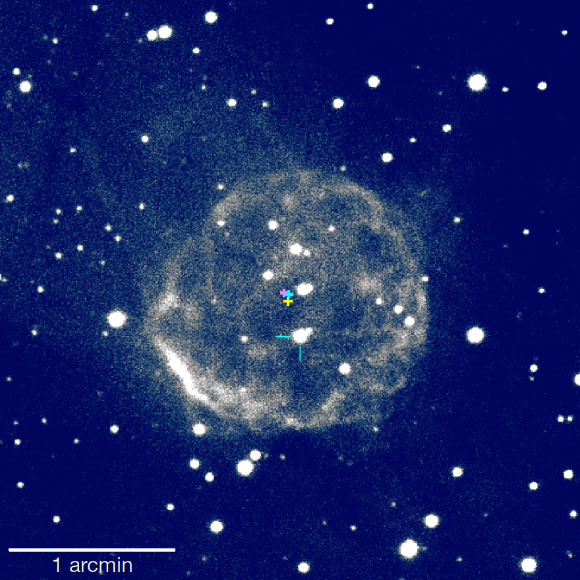

The recovered nova of 1437 and its ejected shell (false color). The now-quiescent star that produced the nova shell is indicated with greenish-blue tick marks; it is far from the shell’s center today. However, its measured motion across the sky places it at the greenish-blue plus sign in 1437. The position of the center of the shell in 2016 and its deduced position in 1437 are indicated with yellow and magenta plus signs, respectively. Image credit: K. Ilkiewicz & J. Mikolajewska.

A nova is a colossal hydrogen bomb produced in a binary system where a Sun-like star is being cannibalized by a white dwarf.

It takes about 100,000 years for the white dwarf to build up a critical layer of hydrogen that it steals from the Sun-like star, and when it does, it blows the envelope off, producing a burst of light that makes the star up to 300,000 times brighter than the sun for anywhere from a few days to a few months.

For years, Dr. Michael Shara, a curator in the American Museum of Natural History’s Department of Astrophysics, has tried to pinpoint the location of the binary star that produced the nova eruption in 1437, along with Dr. Richard Stephenson of Durham University and Dr. Mike Bode of Liverpool John Moores University.

Recently, the team expanded the search field and found the ejected shell of the classical nova.

The researchers confirmed the finding with another kind of historical record: a photographic plate from 1923 taken at the Harvard Observatory station in Peru.

“This is the first nova that’s ever been recovered with certainty based on the Chinese, Korean, and Japanese records of almost 2,500 years,” Dr. Shara said.

“With the 1923 plate, we could figure out how much the star has moved in the century since the photo was taken.”

“Then we traced it back six centuries, and bingo, there it was, right at the center of our shell. That’s the clock, that’s what convinced us that it had to be right.”

Other Harvard plates from the 1940s helped reveal that the system is now a dwarf nova, indicating that so-called ‘cataclysmic binaries’ — novae, novae-like variables, and dwarf novae — are one and the same, not separate entities as has been previously suggested.

“After an eruption, a nova becomes ‘nova-like,’ then a dwarf nova, and then, after a possible hibernation, comes back to being nova-like, and then a nova, and does it over and over again, up to 100,000 times over billions of years,” the scientists explained.

“In the same way that an egg, a caterpillar, a pupa, and a butterfly are all life stages of the same organism, we now have strong support for the idea that these binaries are all the same thing seen in different phases of their lives,” Dr. Shara added.

“The real challenge in understanding the evolution of these systems is that unlike watching the egg transform into the eventual butterfly, which can happen in just a month, the lifecycle of a nova is hundreds of thousands of years. We simply haven’t been around long enough to see a single complete cycle.”

“The breakthrough was being able to reconcile the 580-year-old Korean recording of this event to the dwarf nova and nova shell that we see in the sky today.”

The research appears today in the journal Nature.

_____

M.M. Shara et al. 2017. Proper-motion age dating of the progeny of Nova Scorpii AD 1437. Nature 548: 558-560; doi: 10.1038/nature23644