Both avian and non-avian reptiles excrete excess nitrogen in solid form — colloquially termed ‘urates’ — as an evolutionary adaptation that aids in water conservation. Yet, there are many open questions regarding the composition, structure, and assembly of these biogenic materials. In new research, scientists from Georgetown University, International Centre for Diffraction Data, Chiricahua Desert Museum and Georgia State University analyzed urate excretions from ball python (Python regius) and 20 other reptile species and revealed a clever and highly adaptable system that handles both nitrogenous waste and salts.

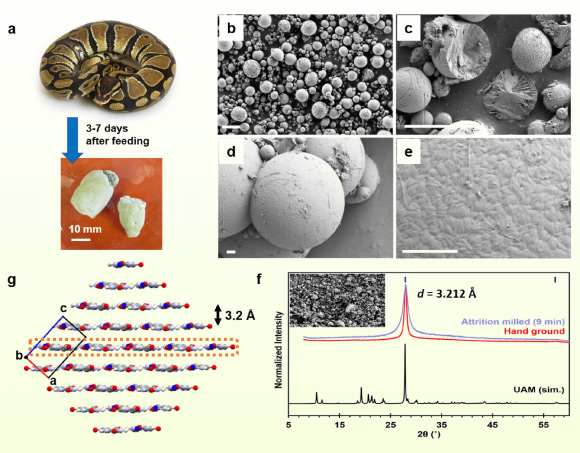

Thornton et al. investigated the solid urine of more than 20 reptile species. Image credit: Thornton et al., doi: 10.1021/jacs.5c10139.

“Most living things have some sort of excretory system — after all, what goes in must come out,” said Georgetown University chemist Jennifer Swift and her colleagues.

“In humans, excess nitrogen in the form of urea, uric acid and ammonia are flushed out in the urine.”

“But many reptiles and birds package up some of those same nitrogen-containing chemicals into solids, or urates, that the animals eliminate through their cloacae.”

Scientists believe that this process may have evolved as a way to conserve water.

“While forming crystals in pee is a potential evolutionary advantage for reptiles, it is a serious issue for humans,” the researchers said.

“When too much uric acid is present in the human body, it can solidify into painful shards in the joints, causing gout, or in the urinary tract as kidney stones.”

In the new study, the authors investigated how reptiles excrete crystalline waste safely, studying urates from more than 20 reptile species.

“This research was really inspired by a desire to understand the ways reptiles are able to excrete this material safely, in the hopes it might inspire new approaches to disease prevention and treatment,” Dr. Swift said.

Microscope images revealed that three species — ball pythons, Angolan pythons and Madagascan tree boas — produced urates consisting of tiny textured microspheres varying from 1 to 10 micrometers wide.

X-ray studies showed that the spheres consist of even smaller nanocrystals of uric acid and water.

Additionally, the scientists discovered that uric acid plays an important role in converting ammonia into a less toxic, solid form.

They speculate that uric acid may actually play a similar protective role in humans.

“Our analysis of urates produced by a range of squamate reptiles serves to elucidate key aspects of the very clever adaptable system they employ to manage nitrogenous waste and salt,” the researchers said.

“With dietary controls in place, an appreciation of how environmental storage and aging can affect sample analyses, and the benefits advancements in instrumentation, the current study provides a much more detailed understanding of the structure and function of biogenic urates.”

“How and where the microspheres are assembled remain open and intriguing questions, though the fact that they are produced by a diverse set of uricotelic species suggests a low energy process seemingly optimized by similar selection regimes.”

“The recognition that uric acid plays a role in ammonia management may have broader implications for human health, though clinical studies are needed to fully substantiate the hypothesis.”

The findings were published today in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

_____

Alyssa M. Thornton et al. Uric Acid Monohydrate Nanocrystals: An Adaptable Platform for Nitrogen and Salt Management in Reptiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc, published online October 22, 2025; doi: 10.1021/jacs.5c10139