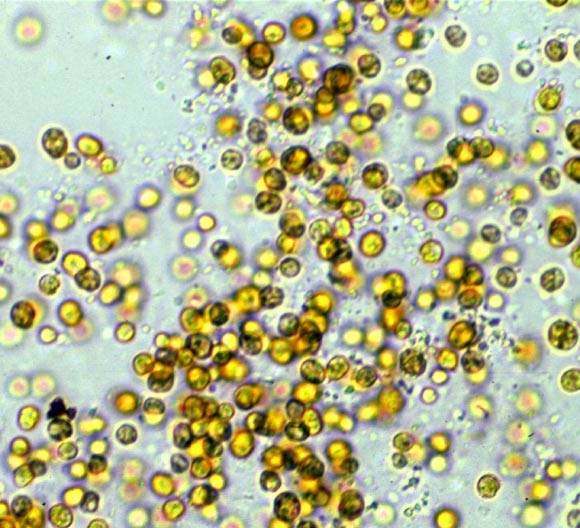

A multinational team of scientists – led by Dr Senjie Lin of Xiamen University and the University of Connecticut – has mapped the genome of Symbiodinium kawagutii, a species in a group of single-celled, ocean-dwelling organisms called dinoflagellates.

Symbiodinium kawagutii is an essential endosymbiont – an organism that lives inside of another organism – of coral reefs.

“It’s essential for the corals, which depend on the dinoflagellate’s photosynthesis for source of sugars and nutritious compounds,” Dr Lin explained.

“Without it, the corals bleach white, cannot grow and usually die. But the relationship doesn’t seem to be essential to the dinoflagellate, although metabolic wastes from the coral host provide an enriched supply of nutrients in the otherwise nutrient-poor oceanic habitat.”

Dr Lin and his colleagues from Singapore, Denmark, Saudi Arabia, the United States, Canada and China, analyzed the entire genome of Symbiodinium kawagutii and compared it to the genetic codes of related organisms that are better understood.

Symbiodinium kawagutii, according to the scientists, has an extremely large genome for a symbiont.

Its genome contains about 1,180 megabases – that’s 1.18 billion base pairs of DNA letters.

Usually endosymbionts, as well as parasites such as malaria to which dinoflagellates are closely related, depend on the cellular machinery of their hosts and lack many genes that free-living organisms have.

“So why does Symbiodinium kawagutii have so many? This is the mystery we don’t understand,” Dr Lin said.

The researchers found some surprising things. For example, they found genes associated with sexual reproduction. Like other dinoflagellates, Symbiodinium kawagutii typically reproduces asexually.

A single dinoflagellate will simply split in two. But when the dinoflagellates turn into cysts, they first reproduce sexually, mixing their genetic material with others, perhaps in the hope that some of the offspring will gain traits better suited to the stressful environment.

Sex related genes have never been found in other dinoflagellates, however. The finding suggests that the species indeed has bad times living in corals.

Dr Lin and co-authors also found that this species has a gene regulatory system that looks like it could regulate certain genes in corals.

In other words, the dinoflagellates may be manipulating their host’s genetic expression to make conditions comfier for themselves.

“The genetic evidence we found is very suggestive that Symbiodinium kawagutii has changed its genetic makeup in the course of its symbiotic history to better suite living in its specific host and cope with stress imposed by climate change and pollution,” said Dr Lin, who is the lead author of a paper in the journal Science.

Understanding the genome of the dinoflagellate Symbiodinium kawagutii will help scientists better understand other dinoflagellates.

_____

Senjie Lin et al. 2015. The Symbiodinium kawagutii genome illuminates dinoflagellate gene expression and coral symbiosis. Science, vol. 350, no. 6261, pp. 691-694; doi: 10.1126/science.aad0408