Genetic analysis of DNA from a female infant found at the Upward Sun River archaeological site in Alaska has revealed a previously unknown Native American population, whom scientists have named ‘Ancient Beringians.’ The research appears in the journal Nature.

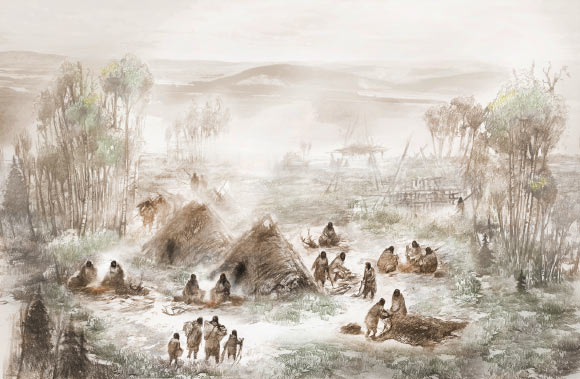

A scientific illustration of the Upward Sun River camp in what is now Interior Alaska. Image credit: Eric S. Carlson / Ben A. Potter.

It is widely accepted that the earliest settlers crossed from Eurasia into Alaska via an ancient land bridge spanning the Bering Strait which was submerged at the end of the last Ice Age.

Issues such as whether there was one founding group or several, when they arrived, and what happened next, are the subject of debate, however.

In the new study, researchers sequenced the full genome of an infant – a girl named Xach’itee’aanenh T’eede Gaay (Sunrise Child-girl) by the local Native community – whose remains were found at the Upward Sun River site in 2013.

To their surprise, the scientists found that although Xach’itee’aanenh T’eede Gaay had lived around 11,500 years ago, long after people first arrived in the region, her genetic information did not match either of the two recognized branches of early Native Americans, which are referred to as Northern and Southern.

Instead, she appeared to have belonged to an entirely distinct Native American population, which they called Ancient Beringians.

“We didn’t know this population existed,” said co-author Professor Ben Potter, from the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

“These data also provide the first direct evidence of the initial founding Native American population, which sheds new light on how these early populations were migrating and settling throughout North America.”

“The DNA from Xach’itee’aanenh T’eede Gaay has provided an unprecedented window into the history of her people,” he said.

“She and a younger female infant found at the Upward Sun River site in 2013 lived about 11,500 years ago and were closely related, likely first cousins. The younger infant has been named Yekaanenh T’eede Gaay (Dawn Twilight Girl-child).”

“It would be difficult to overstate the importance of this newly revealed people to our understanding of how ancient populations came to inhabit the Americas. This new information will allow us a more accurate picture of Native American prehistory. It is markedly more complex than we thought.”

“The Ancient Beringians diversified from other Native Americans before any ancient or living Native American population sequenced to date. It’s basically a relict population of an ancestral group which was common to all Native Americans, so the sequenced genetic data gave us enormous potential in terms of answering questions relating to the early peopling of the Americas,” said study senior author Professor Eske Willerslev, from St John’s College at the University of Cambridge, UK, and the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

“We were able to show that people probably entered Alaska before 20,000 years ago. It’s the first time that we have had direct genomic evidence that all Native Americans can be traced back to one source population, via a single, founding migration event.”

The researchers compared data from the Upward Sun River remains with both ancient genomes, and those of numerous present-day populations.

This allowed the team first to establish that the Ancient Beringian group was more closely related to early Native Americans than their Asian and Eurasian ancestors, and then to determine the precise nature of that relationship and how, over time, they split into distinct populations.

Until now, the existence of two separate Northern and Southern branches has divided academic opinion regarding how the continent was populated. Researchers have disagreed over whether these two branches split after humans entered Alaska, or whether they represent separate migrations.

The genome of Xach’itee’aanenh T’eede Gaay shows that Ancient Beringians were isolated from the common, ancestral Native American population, both before the Northern and Southern divide, and after the ancestral source population was itself isolated from other groups in Asia.

“This means it is likely there was one wave of migration into the Americas, with all subdivisions taking place thereafter,” the authors explained.

According to the team’s timeline, the ancestral population first emerged as a separate group around 36,000 years ago, probably somewhere in northeast Asia.

Constant contact with Asian populations continued until around 25,000 years ago, when the gene flow between the two groups ceased. This cessation was probably caused by brutal changes in the climate, which isolated the Native American ancestors.

“It therefore probably indicates the point when people first started moving into Alaska,” Professor Willerslev said.

Around the same time, there was a level of genetic exchange with an ancient North Eurasian population.

Previous research has shown that a relatively specific, localized level of contact between this group, and East Asians, led to the emergence of a distinctive ancestral Native American population.

Ancient Beringians themselves then separated from the ancestral group earlier than either the Northern or Southern branches around 20,000 years ago. Genetic contact continued with their Native American cousins, however, at least until Xach’itee’aanenh T’eede Gaay was born in Alaska around 8,500 years later.

The geographical proximity required for ongoing contact of this sort led the scientists to conclude that the initial migration into the Americas had probably already taken place when the Ancient Beringians broke away from the main ancestral line.

“It looks as though this Ancient Beringian population was up there, in Alaska, from 20,000 years ago until 11,500 years ago, but they were already distinct from the wider Native American group,” said study first author Dr. Jos Victor Moreno-Mayar, from the University of Copenhagen.

Finally, the team established that the Northern and Southern Native American branches only split between 17,000 and 14,000 years ago which, based on the wider evidence, indicates that they must have already been on the American continent south of the glacial ice.

The divide probably occurred after their ancestors had passed through, or around, the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets — two vast glaciers which covered what is now Canada and parts of the northern United States, but began to thaw at around this time.

The continued existence of this ice sheet across much of the north of the continent would have isolated the southbound travelers from the Ancient Beringians in Alaska, who were eventually replaced or absorbed by other Native American populations.

Although modern populations in both Alaska and northern Canada belong to the Northern Native American branch, the analysis shows that these derive from a later ‘back’ migration north, long after the initial migration events.

“One significant aspect of this research is that some people have claimed the presence of humans in the Americas dates back earlier — to 30,000 years, 40,000 years, or even more,” Professor Willerslev said.

“We cannot prove that those claims are not true, but what we are saying, is that if they are correct, they could not possibly have been the direct ancestors to contemporary Native Americans.”

_____

J. Victor Moreno-Mayar et al. Terminal Pleistocene Alaskan genome reveals first founding population of Native Americans. Nature, published online January 3, 2018; doi: 10.1038/nature25173