A small, insect-eating animal was the common ancestor of placental mammals, an international team of researchers has reported in the journal Science (full paper).

An artist’s rendering of the hypothetical placental ancestor (by Carl Buell)

Their study – the result of a multi-year collaborative project – reveals that placental mammals did not diversify into their present-day lineages until after the extinction event that eliminated about 70 percent of all species on our planet about 65 million years ago. This finding and the reconstruction of the placental ancestor were made with the help of a powerful cloud-based and publicly accessible database called MorphoBank.

“Analysis of this massive dataset shows that placental mammals did not originate during the Mesozoic,” said lead author Dr Maureen O’Leary of Stony Brook University and the American Museum of Natural History.

“Species like rodents and primates did not share the Earth with non-avian dinosaurs but arose from a common ancestor – a small, insect-eating, scampering animal – shortly after the dinosaurs’ demise.”

There are two major types of data for building evolutionary trees of life: phenomic data, observational traits such as anatomy and behavior; and genomic data encoded by DNA. Some scholars have argued that integration of both is necessary for robust tree-building because examining only one type of data leaves out significant information. The evolutionary history of placental mammals, for example, has been interpreted in very different ways depending on the data analyzed. One leading analysis based on genomic data alone predicted that a number of placental mammal lineages existed in the Late Cretaceous and survived the Cretaceous-Paleogene (KPg) extinction. Other analyses place the start of placental mammals near this boundary, and still others set their origin after this event.

“There are over 5,100 living placental species and they exhibit enormous diversity, varying greatly in size, locomotor ability, and brain size,” said study co-author Dr Nancy Simmons of the American Museum of Natural History. “Given this diversity, it’s of great interest to know when and how this clade first began evolving and diversifying.”

The research combines genomic and phenomic data in a simultaneous analysis for a more complete picture of the tree of life.

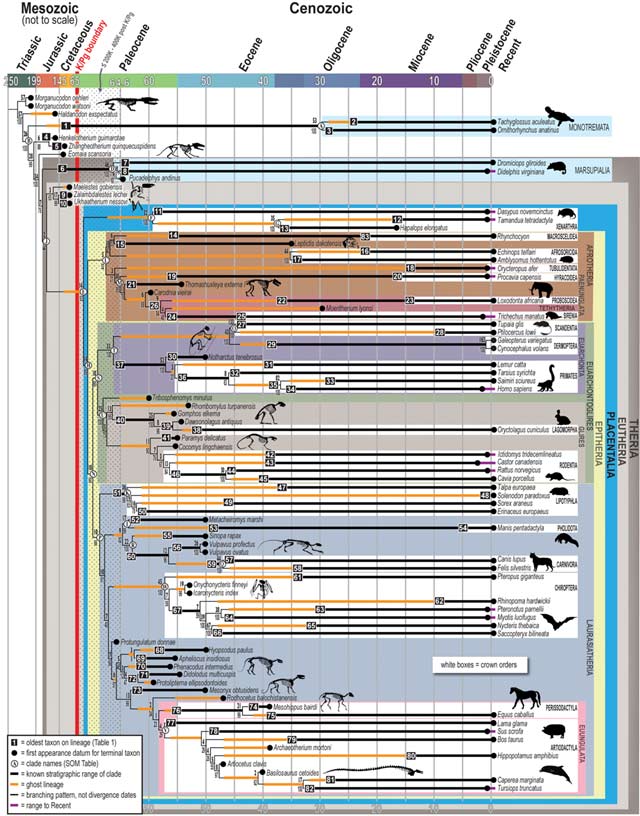

The tree of life produced in the study shows that placental mammals arose rapidly after the KPg extinction, with the original ancestor speciating 200,000-400,000 years after the event.

The new evolutionary tree for placental mammals, created by combining phenomic and genomic data (Stony Brook University/ Luci Betti Nash)

“This is about 36 million years later than the prediction based on purely genetic data,” said co-author Dr Marcelo Weksler of the Museu Nacional-UFRJ in Brazil.

The finding also contradicts a genomics-based model called the ‘Cretaceous-Terrestrial Revolution’ that argues that the impetus for placental mammal speciation was the fragmentation of supercontinent Gondwana during the Jurassic and Cretaceous, millions of years earlier than the KPg event.

“The new tree indicates that the fragmentation of Gondwana came well before the origin of placental mammals and is an unrelated event,” said co-author Dr John Wible of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

As part of the study, researchers used MorphoBank to record phenomic traits for 86 placental mammal species, of which 40 were fossil species. The resulting dataset has more than 4,500 traits detailing characteristics such as the presence or absence of wings, teeth, and certain bones, type of hair cover, and structures found in the brain, as well as over 12,000 supporting images, all publicly available online.

The team reconstructed the anatomy of the placental common ancestor by mapping traits onto the tree most strongly supported by the combined phenomic and genomic data and comparing the features in placental mammals with those seen in their closest relatives. This method, known as optimization, allowed the researchers to determine what features first appeared in the common ancestor of placental mammals and also what traits were retained unchanged from more distant ancestors. The researchers conclude that the common ancestor had features such as a two-horned uterus, a brain with a convoluted cerebral cortex, and a placenta in which the maternal blood came in close contact with the membranes surrounding the fetus, as in humans.

_______

Bibliographic information: Maureen A. O’Leary et al. 2013. The Placental Mammal Ancestor and the Post–K-Pg Radiation of Placentals. Science, vol. 339, no. 6120, pp. 662-667; doi: 10.1126/science.1229237