Vertebrates and arthropods are two of the most successful and frequently fossilized animal groups, but direct evidence of their interaction in deep time — entailing the joint, intimate fossilization of remains from both groups — is extremely rare. New discoveries in Early Cretaceous amber from the locality of San Just in north-eastern Spain show that a symbiotic relationship, likely commensal/mutualistic, was established between beetle larvae feeding on detached feathers and feathered non-avian dinosaurs more than a hundred million years ago.

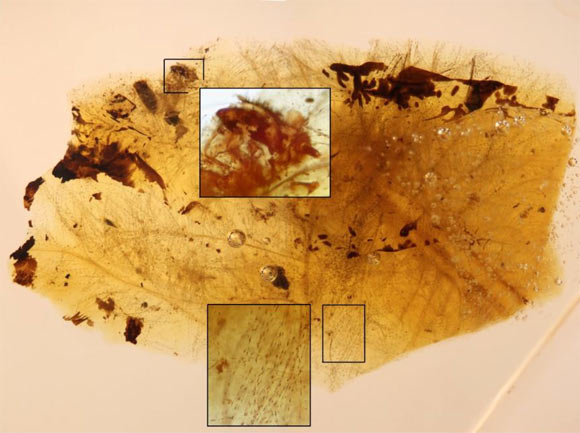

Molt remains of feather-feeding beetle larvae intimately associated with downy feather portions from an unidentified theropod dinosaur in Early Cretaceous amber of Spain. Insets show the head with powerful mandibles of one of the larval molts (top) and the pigmentation pattern of feather second order branches (bottom), with the main stem of one feather at the right of the amber fragment. The length of the amber fragment is 6 mm. Image credit: CN IGME-CSIC.

“Feathers, like hair, are integumentary structures composed of tough, durable keratin,” said Dr. Ricardo Pérez-de la Fuente from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History and his colleagues.

“Despite being a concentrated source of this protein, few groups of arthropods have evolved adaptations to ingest and metabolize keratin — the so-called keratophagy.”

“Aside from its ecological significance, keratophagy is important from an evolutionary standpoint as well, representing, for example, a transitional stage between free-living bark lice and true parasitic lice, in the form of scavenging book lice that commonly feed on nest debris, including keratin.”

“Keratophagy as a trophic specialization entails a parasitic symbiosis if the feeding arthropod guest causes damage in the integument of the vertebrate host.”

“On the contrary, keratophagy can also involve a commensal-mutualistic symbiosis between the host and the arthropod consuming the host’s shed, accumulated integumentary structures, possibly advantageous to the host by cleaning its nest.”

“We present assorted evidence of keratophagy involving beetle and feather remains preserved in Cretaceous amber from Spain, representing a rare instance of arthropod-dinosaur symbiotic relationship in deep time.”

The larval molts preserved in the 105-million-year-old amber from the San Just locality were identified as related to modern skin beetles, or dermestids.

Dermestid beetles are infamous pests of stored products or dried museum collections, feeding on organic materials that are hard for other organisms to digest such as natural fibers.

However, dermestids also play a key role in recycling organic matter in the natural environment, and often inhabit the nests of birds and mammals, where feathers, hair, or skin, accumulate.

The feathers had almost certainly become detached from the host dinosaur, since they showed signs of damage and decay, including fungal strands growing on their surface.

Consequently, the researchers propose that the beetle larvae probably lived in or on a dinosaur nest, where enough feathers could accumulate to sustain a population.

This nest would have been on or close to a resin-producing tree, with the first step leading to the formation of the amber fossils happening when a flow of resin trapped the larvae and feathers, preserving them together for millions of years.

“It is unclear whether the feathered theropod host benefited from the beetle larvae feeding on its detached feathers in this plausible nest setting,” Dr. Pérez-de la Fuente said.

“However, the theropod was most likely unharmed by the activity of the larvae since our data indicate that these did not feed on ‘living’ plumage.”

“Furthermore, the larvae lacked defensive, bristle-like structures which among modern dermestids can irritate the skin of nest hosts, even killing them.”

“The emerging view is that some groups of arthropod symbionts of feathered theropods in the Late Mesozoic transitioned to modern birds in the Cenozoic, Earth’s current geological era,” Dr. Pérez-de la Fuente added.

“I suspect that as more fossils are unearthed we will keep finding more key evidence on how two of the most prominent groups of animals, arthropods and vertebrates, have influenced each other’s fascinating, and often intertwined, evolutionary pathways.”

A paper on the findings appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

_____

Enrique Peñalver et al. 2023. Symbiosis between Cretaceous dinosaurs and feather-feeding beetles. PNAS 120 (17): e2217872120; doi: 10.1073/pnas.2217872120