A head of Medusa has been unearthed by a team of archaeologists digging at the site of Antiochia ad Cragum, an ancient Roman city on Turkey’s southern coast. In addition, the team – led by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln – has uncovered the ruins of two large buildings: a bouleuterion (city council house) and a Byzantine-era basilica.

An aerial view of the bouleuterion recently discovered at the site of Antiochia ad Cragum. Test trenches reveal, among other things, a curved marble bench for dignitaries, supports for wooden seats for a general audience and a marble-paved orchestra area. Image credit: Michael Hoff / University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Since 2005, the team has been excavating the remains of Antiochia ad Cragum, which was founded by Antiochus of Commagene, a client-king of Rome, in the middle of the 1st century CE. By the 4th century, the area was a key site for the development of Christianity.

“This region is not well understood in terms of history and archaeology. It’s not a place in which archaeologists have spent a lot of time, so everything we find adds more evidence to our understanding of this area of the Roman Empire,” said Prof. Michael Hoff of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, director of the excavation.

“Antiochia ad Cragum had many of the trappings expected of a Roman provincial city – temples, baths, markets and colonnaded streets.”

“The city thrived during the empire from an economy focused on agricultural products, especially wine and lumber.”

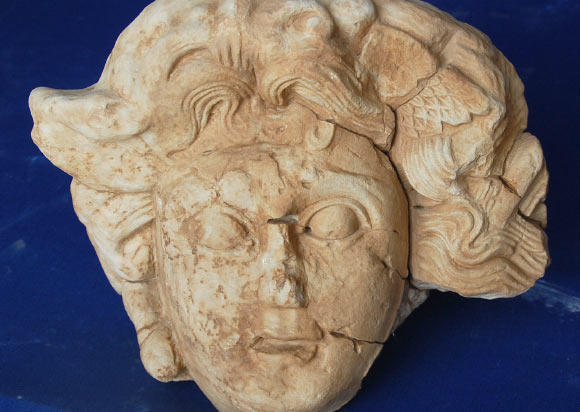

The newly-unearthed Medusa’s head, which once guarded a small temple or altar, is carved in marble and was found in the rubble near a previously discovered marble mosaic that dates to Roman times.

“Medusa was a Greek mythological creature with serpents for hair and a gaze that turned living people to stone,” the archaeologists explained.

“People in ancient times adopted Medusa’s head as a protective symbol to ward off intruders.”

The marble head of Medusa recently discovered at the site. Image credit: Michael Hoff / University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Nearby, on the opposite side of what once was a Roman bath, the archaeologists uncovered part of the ruins of a bouleuterion.

They used chain saws to remove thorny brush that covered a bowl-shaped depression behind the bath house.

After removing more than 4 feet of earth in a test trench, Prof. Hoff and his colleagues realized they had found the city’s seat of government.

They uncovered a semi-circular marble bench to seat dignitaries that faced a platform and orchestra area paved in marble. Behind the bench were two radiating sets of marble stairs, which likely led to grandstand seats.

The proletariats’ seats probably were made of wood and no longer exist. However, the archeologists recovered about 20 pounds of ancient nails and hundreds of roof tiles scattered in the area, evidence of the building’s former structure. They will continue excavating the bouleuterion next year.

“That was one of our best finds. This was truly the heart of the ancient city,” Prof. Hoff said.

The team also found the ruins of a basilica, the fourth and largest Christian church found so far in the city center of Antiochia ad Cragum; as well as evidence that a hilltop building they have dubbed the Acropolis was used as a Christian monastery during the Byzantine Empire.

The new discoveries offer clues to how the people of Antiochia lived as well as the religious and social changes that shaped their city.

Yet the greatest mystery remains unanswered: “why was the city abandoned so many years ago, silenced beneath more than 6 feet of earth?”

“Something happened. It’s possible that earthquakes damaged the city to a degree that people just decided to abandon it. Or it’s possible we can find archaeological evidence that people lived here until the arrival of the Seljuk Turks in about 1100,” Prof. Hoff said.

“The Seljuk Turks defeated the Byzantine Empire in 1071, opening the way for the Turkish occupation of Anatolia, the peninsula between the Black Sea, the Aegean Sea and the Mediterranean Sea, where Turkey is located. The Turks forced people to leave other old Roman cities in the region,” he added.