Archaeologists have discovered Oldowan stone tools in three distinct archaeological horizons, spanning approximately 300,000 years (2.75 to 2.44 million years ago), at the site of Namorotukunan, part of the Koobi Fora Formation in the northeastern portion of the Turkana Basin in Kenya’s Marsabit district. The discovery suggests continuity in tool-making practices over time, with evidence of systematic selection of rock types.

The 2.58-million-year-old stone tool from the site of Namorotukunan in Kenya. Image credit: Braun et al., doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-64244-x.

The earliest phases of tool manufacture, dating back to over 3 million years ago, highlight percussive technology, which is ubiquitous in hominin records and shared with other primates.

Tool use, associated with extractive foraging, is a recurring trait in some extant primates.

The oldest systematic production of sharp-edged stone artifacts, known as the Oldowan, is found in the hominin behavioral record at eastern African sites: Ledi-Geraru and Gona in the Afar Basin (2.6 million years ago), Ethiopia, and Nyayanga in western Kenya (2.6-2.9 million years ago).

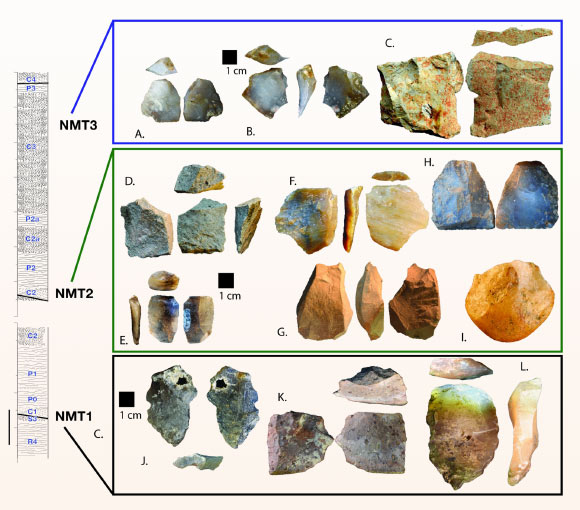

Professor David R. Braun, an anthropologist at the George Washington University and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and colleagues discovered multiple assemblages of stone tools from three horizons, with age estimates at 2.75, 2.58, and 2.44 million years ago, at the site of Namorotukunan.

“This site reveals an extraordinary story of cultural continuity,” Professor Braun said.

“What we’re seeing isn’t a one-off innovation — it’s a long-standing technological tradition.”

“Our findings suggest that tool use may have been a more generalized adaptation among our primate ancestors,” said Dr. Susana Carvalho, director of science at the Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique.

“Namorotukunan offers a rare lens on a changing world long gone — rivers on the move, fires tearing through, aridity closing in — and the tools, unwavering.”

Stone tools recovered from three horizons at the site of Namorotukunan in Kenya. Image credit: Braun et al., doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-64244-x.

“For 300,000 years, the same craft endures — perhaps revealing the roots of one of our oldest habits: using technology to steady ourselves against change,” said Dr. Dan V. Palcu Rolier, a researcher at GeoEcoMar, Utrecht University and the University of São Paulo.

“Early hominins engineered sharp-edged stone tools with extraordinary consistency, showing advanced skill and knowledge passed down across countless generations.”

Using volcanic ash dating, magnetic signals frozen in ancient sediments, chemical signatures of rocks, and microscopic plant remains, the researchers pieced together an epic climatic saga that provides context for understanding the role of technology in human evolution.

These toolmakers lived through radical environmental upheavals. Their adaptable technology helped unlock new diets, including meat, turning hardship into a survival advantage.

“These finds show that by about 2.75 million years ago, hominins were already good at making sharp stone tools, hinting that the start of the Oldowan technology is older than we thought,” said Dr. Niguss Baraki, a researcher at the George Washington University.

“At Namorotukunan, cutmarks link stone tools to meat eating, revealing a broadened diet that endured across changing landscapes,” added Dr. Frances Forrest, a researcher at Fairfield University.

“The plant fossil record tells an incredible story: the landscape shifted from lush wetlands to dry, fire-swept grasslands and semi-deserts,” said Dr. Rahab N. Kinyanjui, a researcher at the National Museums of Kenya and the Max Planck Institute for Geoanthropology.

“As vegetation shifted, the toolmaking remained steady. This is resilience.”

The results appear today in the journal Nature Communications.

_____

D.R. Braun et al. 2025. Early Oldowan technology thrived during Pliocene environmental change in the Turkana Basin, Kenya. Nat Commun 16, 9401; doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-64244-x