An international team of citizen scientists and professional astronomers has discovered a system of at least five massive exoplanets, orbiting the Sun-like star K2-138. This planetary system is approximately 792 light-years away toward the constellation Aquarius. A paper reporting this discovery is published in the Astronomical Journal (arXiv.org preprint).

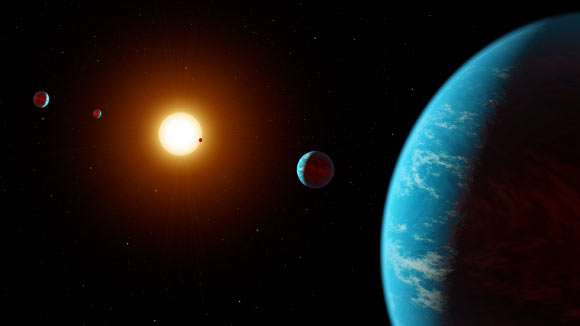

Artist’s visualization of the K2-138 system, the first multi-planet system discovered by citizen scientists. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / R. Hurt, IPAC.

K2-138, also known as 2MASS J23154776-1050590 and EPIC 245950175, is a moderately bright K-type star.

It is slightly smaller and cooler than our Sun and hosts at least five massive planets: K2-138b, c, d, e, and f.

The alien worlds are all between the size of Earth and Neptune: planet K2-138b may potentially be rocky, but planets K2-138c, d, e, and f likely contain large amounts of ice and gas.

All five planets have orbital periods shorter than two weeks (2.35, 3.56, 5.40, 8.26, and 12.76 days) and are incredibly hot, ranging from 800 to 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (427-982 degrees Celsius).

The planets also appear to orbit their star in concentric circles, forming a tightly packed planetary system, unlike our own elliptical, far-flung Solar System.

“The credit for this planetary discovery goes mainly to the citizen scientists — about 10,000 from the around the world — who pored through publicly available data from K2, a follow-on to NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope mission,” the astronomers said.

“K2’s data comprises light curves — graphs of light intensity from individual stars in the sky. A dip in starlight indicates a possible transit, or crossing, of an object such as a planet in front of its star.”

The original Kepler mission was managed mostly by a dedicated team of trained scientists and astronomers who were tasked with analyzing incoming data, looking for transits, and classifying exoplanet candidates. In contrast, K2 has been driven mainly by decentralized, community-led efforts.

In 2017, MIT Professor Ian Crossfield worked with fellow astronomer Dr. Jesse Christiansen at Caltech to make the K2 data public and enlist as many volunteers as they could in the search for exoplanets.

They used a popular citizen-scientist platform called Zooniverse to create their own project, dubbed Exoplanet Explorers.

For the new project, the scientists first ran a signal-detection algorithm to identify potential transit signals in the K2 data, then made those signals available on the Zooniverse platform. They designed a training program to first teach users what to look for in determining whether a signal is a planetary transit.

“We put all this data online and said to the public, ‘Help us find some planets.’ It’s exciting, because we’re getting the public excited about science, and it’s really leveraging the power of the human cloud,” Professor Crossfield said.

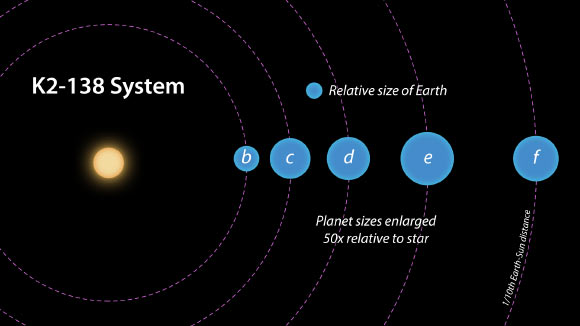

Artist’s concept of a top-down view of the K2-138 system discovered by citizen scientists, showing the orbits and relative sizes of the five known planets. Orbital periods of the five planets, shown to scale, fall close to a series of 3:2 mean motion resonances. This indicates that the planets orbiting K2-138, which likely formed much farther away from the star, migrated inward slowly and smoothly. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / R. Hurt, IPAC.

The astronomers then looked more closely at the classifications flagged by the public and determined that many of them were indeed objects of interest.

In particular, the effort identified 44 Jupiter-sized, 72 Neptune-sized, and 44 Earth-sized planets, as well as 53 super-Earths.

One set of signals in particular drew the researchers’ interest. The signals appeared to resemble transits from five separate planets orbiting a single star, K2-138.

To follow up, they collected supporting data of the star taken previously from ground-based telescopes, which helped them to estimate the star’s size, mass, and temperature.

They then took some additional measurements to ensure that it was indeed a single star, and not a cluster of stars.

By looking closely at the light curves associated with the star, they determined that it was ‘extremely likely’ that five planet-like objects were crossing in front of the star.

From their estimates of the star’s parameters, they inferred the sizes of the five planets along with their orbits.

“The clockwork-like orbital architecture of this planetary system is keenly reminiscent of the Galilean satellites of Jupiter,” said Caltech astronomer Dr. Konstantin Batygin, who was not involved with the study.

“Orbital commensurabilities among planets are fundamentally fragile, so the present-day configuration of the K2-138 planets clearly points to a rather gentle and laminar formation environment of these distant worlds.”

_____

Jessie L. Christiansen et al. 2018. The K2-138 System: A Near-resonant Chain of Five Sub-Neptune Planets Discovered by Citizen Scientists. AJ 155, 57; doi: 10.3847/1538-3881/aa9be0