Paleontologists have identified the 410-million-year-old specimens of Spongiophyton nanum from the Ponta Grossa Formation in the Paraná Basin of Brazil as one of the oldest and most widespread lichens from the fossil record.

An artistic reconstruction of Spongiophyton nanum during the Early Devonian in the high latitude depositional system of the Paraná Basin. Image credit: J. Lacerda.

The colonization of land and the subsequent evolution of complex land ecosystems was one of the most marked evolutionary events in the history of life.

This process has markedly affected both land and marine settings, contributing to drawdown of atmospheric carbon dioxide, increased weathering and nutrient input to oceans, soil development, and the evolution of major groups of terrestrial animals.

Early plants are well-known to have been central to the colonization of land, particularly producing the first plant ecosystems.

The earliest evidence of ancient land plants occurs as cryptospores by the Middle Ordovician (460 million years ago), while macrofossils of early vascular plants appear in Silurian deposits (443 to 420 million years ago).

However, the role and presence of lichens during certain steps of the terrestrialization process remain unclear.

“Spongiophyton nanum shows a similar combination of fungi and algae to modern lichens,” said Dr. Bruno Becker-Kerber from Harvard University.

“Our findings show that lichens were not marginal organisms, but key pioneers in the transformation of Earth’s surface.”

“They helped create the soil that allowed plants and animals to take hold and diversify on land.”

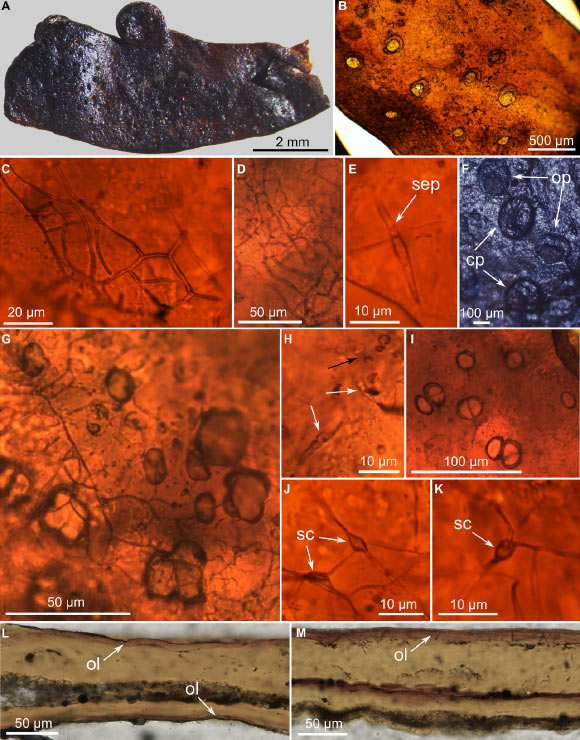

Morphology and internal structures of Spongiophyton nanum. Image credit: Becker-Kerber et al., doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adw7879.

The team’s results suggest ancient lichens first evolved in the cold polar regions of the supercontinent Gondwana, in areas that correspond to modern-day South America and Africa.

“Spongiophyton nanum is an extraordinary fossil with extraordinary preservation. It is essentially mummified with organic matter intact,” said Australian National University’s Professor Jochen Brocks.

“The tough material in simple plants is cellulose. Lichens, on the other hand, are decidedly weird — they are composed of the same material that makes beetles and other insects tough — chitin.”

“Chitin is loaded with the element nitrogen. When we analyzed Spongiophyton nanum, we got an enormous nitrogen signal, never seen before.”

“You rarely get such a clear result, it was a Eureka moment.”

“Lichens still play a crucial role today in producing soil, recycling nutrients, and capturing carbon in extreme environments from deserts to polar regions.”

“Yet their origins have remained obscure due to their fragile nature and scarce fossil record.”

“This work shows how essential it is to combine conventional methodologies with cutting-edge techniques,” said Dr. Nathaly L. Archilha, a researcher at the Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory.

“Initial measurements guided us toward key regions of interest, and only then could we collect 3D nanometric imaging, revealing the complex fungal and algal networks that define Spongiophyton nanum as a true lichen.”

The team’s paper was published this week in the journal Science Advances.

_____

Bruno Becker-Kerber et al. 2025. The rise of lichens during the colonization of terrestrial environments. Science Advances 11 (44); doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adw7879