In a new study published in the journal Nature, scientists used DNA samples collected from 2,039 people to create the fine-scale genetic map of British Isles.

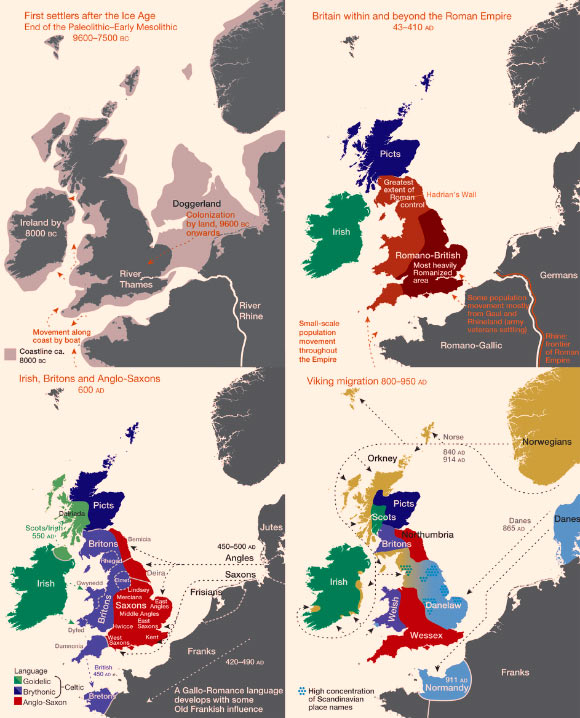

Major events in the peopling of the British Isles. Top left: the routes taken by the first settlers after the last ice age. Top right: Britain during the period of Roman rule. Bottom left: the regions of ancient British, Irish and Saxon control. Bottom right: the migrations of Norse and Danish Vikings; the main regions of Norse Viking (light brown) and Danish Viking (light blue) settlement are shown. Image credit: Stephen Leslie et al / EuroGeographics.

The team, led by Dr Peter Donnelly of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics in Oxford, UK, analyzed the DNA of people from rural areas of the UK, whose four grandparents were all born within 80 km of each other.

Because a quarter of our genome comes from each of our grandparents, Dr Donnelly and his colleagues were effectively sampling DNA from these ancestors, allowing a snapshot of UK genetics in the late 19th century.

The scientists found that the samples could be grouped into 17 clusters, which coincided strongly with geographical areas.

They then went on to compare each cluster’s DNA with samples from 6,209 people in ten European countries with a history of migration to the British Isles.

The results confirm that successive waves of invaders never wiped out the existing populations but interbred with them.

According to the scientists, “the majority of eastern, central and southern England is made up of a single, relatively homogeneous, genetic group with a significant DNA contribution from Anglo-Saxon migrations (10-40 percent of total ancestry). This settles a historical controversy in showing that the Anglo-Saxons intermarried with, rather than replaced, the existing populations.”

“There are separate genetic groups in Cornwall and Devon, with a division almost exactly along the modern county boundary.”

“The population in Orkney emerged as the most genetically distinct, with 25 percent of DNA coming from Norwegian ancestors. This shows clearly that the Norse Viking invasion (9th century) did not simply replace the indigenous Orkney population.”

There is no obvious genetic signature of the Danish Vikings, who controlled large parts of England from the 9th century.

“The Welsh appear more similar to the earliest settlers of Britain after the last ice age than do other people in the UK.

The scientists said there was not a single Celtic genetic group. “In fact the Celtic parts of the UK (Scotland, Northern Ireland, Wales and Cornwall) are among the most different from each other genetically. For example, the Cornish are much more similar genetically to other English groups than they are to the Welsh or the Scots.”

“There is genetic evidence of the effect of the Landsker line – the boundary between English-speaking people in south-west Pembrokeshire and the Welsh speakers in the rest of Wales, which persisted for almost a millennium.”

The study suggests there was a substantial migration across the channel after the original post-Ice-Age settlers, but before Roman times.

“DNA from these migrants spread across England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland, but had little impact in Wales.”

“Many of the genetic clusters show similar locations to the tribal groupings and kingdoms around end of the 6th century, after the settlement of the Anglo-Saxons, suggesting these tribes and kingdoms may have maintained a regional identity for many centuries.”

“Beyond the fascinating insights into our history, this information could prove very useful from a health perspective, as building a picture of population genetics at this scale may in future help us to design better genetic studies to investigate disease,” said Dr Michael Dunn of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics.

_____

Stephen Leslie et al. 2015. The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population. Nature 519, 309–314; doi: 10.1038/nature14230