The first comprehensive genomic study of Indigenous Australians has revealed that they are indeed the direct descendants of Australia’s earliest settlers and diverged from their Papuan neighbors about 37,000 years ago. The study also confirmed that all modern non-African populations are descended from a single wave of migrants, who left Africa approximately 72,000 years ago.

Depiction of the Jarijari (Nyeri Nyeri) people near Merbein engaged in recreational activities, including a type of Aboriginal football, by William Blandowski & Gustav Mützel, 1857.

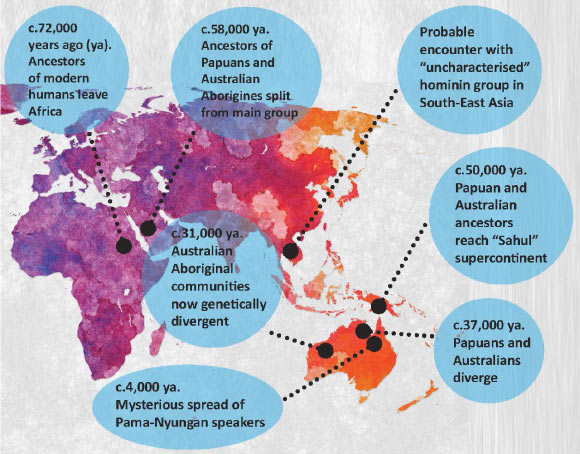

Anatomically modern humans are known to have left Africa 72,000 years ago, eventually spreading across Asia and Europe.

Outside Africa, Australia has one of the longest histories of continuous human occupation, dating back about 50,000 years.

But who exactly were the first people to settle there? Such a question has obvious political implications and has been hotly debated for decades.

Some scientists believe that Australians and Papuans stemmed from an earlier migration than the ancestors of Eurasian peoples. Others believe that they split from Eurasian progenitors within Africa itself, and left the continent in a separate wave.

Until the present study, however, the only genetic evidence for Indigenous Australians came from one tuft of hair and two unidentified cell lines. The new research dramatically improves that picture.

The authors sequenced the complete genomes of 83 Indigenous Australians (speakers of Pama–Nyungan languages) and 25 Papuans from the New Guinea Highlands.

They modeled the likely genetic impact of different human dispersals from Africa and towards Australia, looking for patterns that best matched the data they acquired.

“Our results suggest that, rather than having left in a separate wave, most of the genomes of Papuans and Indigenous Australians can be traced back to a single ‘Out of Africa’ event which led to modern worldwide populations,” said study co-lead author Dr. Manjinder Sandhu, a researcher at the Sanger Institute and the University of Cambridge.

“There may have been other migrations, but the evidence so far points to one exit event.”

“Discussions have been intense as to what extent Indigenous Australians represent a separate Out-of-Africa exit to those of Asians and Europeans,” study co-lead author Prof. Laurent Excoffier, from the SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics and the University of Bern.

“We find that, once we take into account admixture with archaic humans, the vast majority of the Indigenous Australian genetic makeup comes from the same African exit as other non-Africans.”

The Papuan and Australian ancestors did, however, diverge early from the rest, around 58,000 years ago.

By comparison, European and Asian ancestral groups only become distinct in the genetic record around 42,000 years ago.

Around 50,000 years ago Papuan and Australian groups reached Sahul – a prehistoric supercontinent that originally united New Guinea, Australia and Tasmania, until these regions were separated by rising sea levels approximately 10,000 years ago.

The team charted several further ‘divergences’ in which various parts of the population broke off and became genetically isolated from others.

Interestingly, Papuans and Indigenous Australians appear to have diverged about 37,000 years ago – long before they became physically separated by water.

The cause is unclear, but one reason may be the early flooding of the Carpentaria basin, which left Australia connected to New Guinea by a strip of land that may have been unfavorable for human habitation.

Once in Australia, the ancestors of today’s Aboriginal communities remained almost completely isolated from the rest of the world’s population until just a few thousand years ago, when they came into contact with some Asian populations, followed by European travelers in the 18th century.

Indeed, by 31,000 years ago, most Aboriginal communities were genetically isolated from each other. This divergence was most likely caused by environmental barriers; in particular the evolution of an almost impassable central desert as the Australian continent dried out.

“The genetic diversity among Indigenous Australians is amazing,” said study first author Dr. Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas, from the SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, the Centre for GeoGenetics of Copenhagen and the University of Bern.

“Perhaps because the continent has been inhabited for such a long time by Indigenous Australians we find that groups from southwestern desert Australia are more genetically different from groups of northeastern Australia than are for example Native Americans and Siberians, and this is within a single continent.”

The study incorporates several new findings about early human populations, while charting their progress across Asia towards Australia. Image credit: St John’s College.

Dr. Sandhu, Prof. Excoffier, Dr. Malaspinas and their colleagues were also able to reappraise traces of DNA which come from an ancient, extinct human species and are found in Indigenous Australians.

These have traditionally been attributed to encounters with Denisovans – a group known from DNA samples found in Siberia.

In fact, the study suggests that they were from an uncharacterized — and perhaps unknown — early human species.

“We don’t know who these people were, but they were a distant relative of Denisovans, and the Papuan/Australian ancestors probably encountered them close to Sahul,” said study co-lead author Prof. Eske Willerslev, who holds posts at the University of Cambridge, the Sanger Institute and the University of Copenhagen.

The study also offers an intriguing new perspective on how Aboriginal culture itself developed, raising the possibility of a mysterious, internal migration 4,000 years ago.

About 90% of Aboriginal communities today speak languages belonging to the ‘Pama-Nyungan’ linguistic family.

The study finds that all of these people are descendants of the founding population which diverged from the Papuans 37,000 years ago, then diverged further into genetically isolated communities.

This, however, throws up a long-established paradox. Language experts are adamant that Pama-Nyungan languages are much younger, dating back 4,000 years, and coinciding with the appearance of new stone technologies in the archaeological record.

Scientists have long puzzled over how – if these communities were completely isolated from each other and the rest of the world – they ended up sharing a language family that is much younger? The traditional answer has been that there was a second migration into Australia 4,000 years ago, by people speaking this language.

But the present study finds no evidence of this. Instead, the authors uncovered signs of a tiny gene flow, indicating a small population movement from north-east Australia across the continent, potentially at the time the Pama-Nyungan language and new stone tool technologies appeared.

These intrepid travelers, who must have braved forbidding environmental barriers, were small in number, but had a significant, sweeping impact on the continent’s culture.

Mysteriously, however, the genetic evidence for them then disappears. In short, their influential language and culture survived – but they, as a distinctive group, did not.

This research was published online September 21, 2016 in the journal Nature.

_____

Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas et al. A genomic history of Aboriginal Australia. Nature, published online September 21, 2016; doi: 10.1038/nature18299