Scientists from MIT and elsewhere have identified chemical fossils that may have been left by ancient sponges in rocks more than 541 million years old. These chemical fossils are special types of steranes, which are the geologically stable form of sterols that are found in the cell membranes of complex organisms. The researchers traced these special steranes to a class of sea sponges known as demosponges.

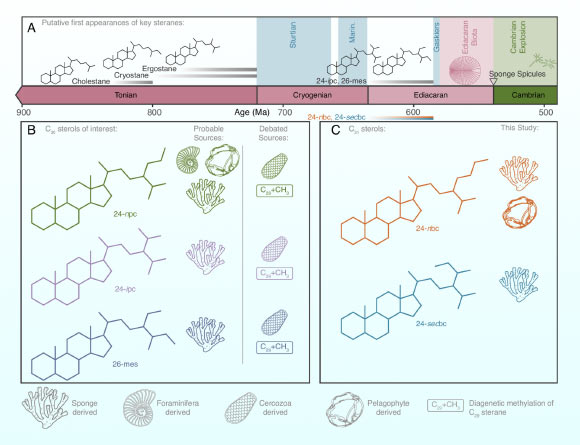

Pictorial representation of the timeline for ancient steranes, highlighting key compounds and their possible biogenic sources. Image credit: Shawar et al., doi: 10.1073/pnas.2503009122.

“We don’t know exactly what these organisms would have looked like back then, but they absolutely would have lived in the ocean, they would have been soft-bodied, and we presume they didn’t have a silica skeleton,” said MIT Professor Roger Summons.

In 2009, the authors identified the first chemical fossils that appeared to derive from ancient sponges.

They analyzed rock samples from an outcrop in Oman and found a surprising abundance of steranes that they determined were the preserved remnants of 30-carbon (C30) sterols — a rare form of steroid that they showed was likely derived from ancient sea sponges.

The steranes were found in rocks that were very old and formed during the Ediacaran period (635 to 541 million years ago).

This period took place just before the Cambrian, when the Earth experienced a sudden and global explosion of complex multicellular life.

The team’s discovery suggested that ancient sponges appeared much earlier than most multicellular life, and were possibly one of Earth’s first animals.

However, soon after these findings were released, alternative hypotheses swirled to explain the C30 steranes’ origins, including that the chemicals could have been generated by other groups of organisms or by nonliving geological processes.

The current study reinforces the earlier hypothesis that ancient sponges left behind this special chemical record, as the researchers have identified a new chemical fossil in the same Precambrian rocks that is almost certainly biological in origin.

Just as in their previous work, they looked for chemical fossils in rocks that date back to the Ediacaran period.

They acquired samples from drill cores and outcrops in Oman, western India, and Siberia, and analyzed the rocks for signatures of steranes, the geologically stable form of sterols found in all eukaryotes (plants, animals, and any organism with a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles).

“You’re not a eukaryote if you don’t have sterols or comparable membrane lipids,” Professor Summons said.

The chemical fossil the researchers identified in 2009 was a 30-carbon sterol.

What’s more, the team determined that the compound could be synthesized because of the presence of a distinctive enzyme which is encoded by a gene that is common to demosponges.

“It’s very unusual to find a sterol with 30 carbons,” said Dr. Lubna Shawar, a researcher at Caltech.

In the current study, the scientists focused on the chemistry of these compounds and realized the same sponge-derived gene could produce an even rarer sterol, with 31 carbon atoms (C31).

When they analyzed their rock samples for C31 steranes, they found it in surprising abundance, along with the aforementioned C30 steranes.

“These special steranes were there all along,” Dr. Shawar said.

“It took asking the right questions to seek them out and to really understand their meaning and from where they come.”

The researchers also obtained samples of modern-day demosponges and analyzed them for C31 sterols.

They found that, indeed, the sterols — biological precursors of the C31 steranes found in rocks — are present in some species of contemporary demosponges.

Going a step further, they chemically synthesized eight different C31 sterols in the lab as reference standards to verify their chemical structures.

Then, they processed the molecules in ways that simulate how the sterols would change when deposited, buried, and pressurized over hundreds of millions of years.

They found that the products of only two such sterols were an exact match with the form of C31 sterols that they found in ancient rock samples.

The presence of two and the absence of the other six demonstrates that these compounds were not produced by a random nonbiological process.

The findings, reinforced by multiple lines of inquiry, strongly support the idea that the steranes that were found in ancient rocks were indeed produced by living organisms, rather than through geological processes.

What’s more, those organisms were likely the ancestors of demosponges, which to this day have retained the ability to produce the same series of compounds.

“It’s a combination of what’s in the rock, what’s in the sponge, and what you can make in a chemistry laboratory,” Professor Summons said.

“You’ve got three supportive, mutually agreeing lines of evidence, pointing to these sponges being among the earliest animals on Earth.”

“In this study we show how to authenticate a biomarker, verifying that a signal truly comes from life rather than contamination or non-biological chemistry,” Dr. Shawar said.

The new results were published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

_____

Lubna Shawar et al. 2025. Chemical characterization of C31 sterols from sponges and Neoproterozoic fossil sterane counterparts. PNAS 22 (41): e2503009122; doi: 10.1073/pnas.2503009122