A team of astronomers, led by Dr Francesco Tombesi of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and the University of Maryland, has observed two related phenomena in the same galaxy, IRAS F11119+3257: a huge galactic outflow, seen by ESA’s Herschel Space Observatory, and a black-hole driven wind at the galaxy’s center, detected with the Suzaku X-ray telescope.

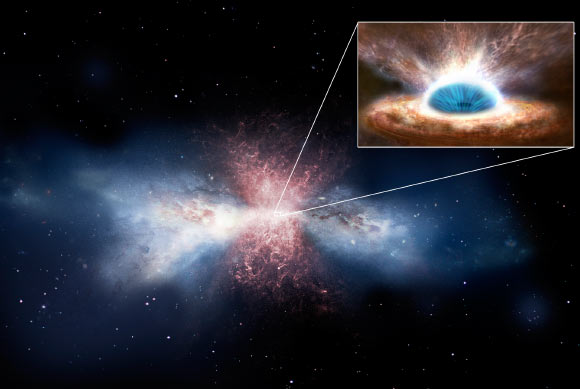

This image shows an artistic representation of an active supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy, which is driving powerful winds that are triggering the outflow of large amounts of molecular gas in the interstellar material of its host galaxy; such outflows can eventually sweep away most of the galaxy’s reservoir of ‘star-making’ gas, possibly bringing an end to star formation on a galactic scale. The first direct evidence supporting this feedback scenario was made possible by combining far-infrared observations from ESA’s Herschel, which detected large-scale outflows of molecular gas in the galaxy IRAS F11119+3257, with X-ray data from the Suzaku X-ray observatory, which could sense the winds close to the black hole. Image credit: ESA / ATG medialab.

Galaxies have been forming stars since the Universe was only a few hundred million years old, but over the past 10 billion years this activity has declined.

In fact, while the formation of stars reached its peak a few billion years after the Big Bang, galaxies in the present-day Universe are no longer such stellar factories, with a typical galaxy giving birth to just a few new stars every year.

Scientists have long been wondering about the physical processes that regulate star formation in galaxies: what slowed it down over cosmic history, preventing galaxies from turning all of their gas into stars; why did some galaxies shut down their production of stars entirely?

They suspected that the activity driven by the central supermassive black holes might be responsible for triggering such a feedback mechanism, but until recently there was no direct proof that this scenario could be acted out on a global galactic scale.

“This is the first time that we see a supermassive black hole in action, blowing away the galaxy’s reservoir of star-making gas,” said Dr Tombesi, who is the first author on the study published in the journal Nature.

Combining Herschel infrared observations with new data from the Suzaku observatory, Dr Tombesi and his colleagues detected the winds close to the central supermassive black hole as well as their effect in pushing galactic gas away in IRAS F11119+3257, an ultraluminous infrared galaxy located approximately 2.3 billion light-years away.

The winds start small and fast, gusting at about 25 percent the speed of light near the IRAS F11119+3257’s black hole and blowing away about the equivalent of one solar mass of gas every year.

As they progress outwards, the winds slow but sweep up an additional few hundred solar masses of gas molecules per year and push it out of the galaxy.

“While the initial wind only blows away about the equivalent of one solar mass of ionized gas every year, the outflow of molecular gas is much more substantial, affecting at least the equivalent of a few hundred solar masses per year,” said co-author Dr Marcio Meléndez, also of the University of Maryland.

The findings support the idea that black holes might ultimately stop stars forming in their host galaxies.

_____

F. Tombesi et al. 2015. Wind from the black-hole accretion disk driving a molecular outflow in an active galaxy. Nature 519, 436–438; doi: 10.1038/nature14261