Hupehsuchus nanchangensis, a species of marine reptile that lived between 249 and 247 million years ago in what is now China, had soft structures such as an expanding throat region to allow it to engulf great masses of water containing shrimp-like prey, and baleen whale-like structures to filter food items as it swam forward.

Reconstruction of Hupehsuchus nanchangensis about to engulf a shoal of shrimps. Image credit: Shunyi Shu & Long Cheng, Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey.

Filter feeding involves an animal moving through the water and extracting small organisms, such as krill or plankton, for food via sieve-type mechanisms.

Filter feeding fish such as basking sharks use their gills to retain food from water, while filter feeding whales sift material through baleen plates.

To date, there has been very little evidence suggesting that ancient marine reptiles from the Mesozic era (252 to 66 million years ago) were filter feeders due to a lack of the appropriate features in fossil records.

“We were amazed to discover these adaptations in such an early marine reptile,” said Dr. Zichen Fang, a paleontologist at the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey.

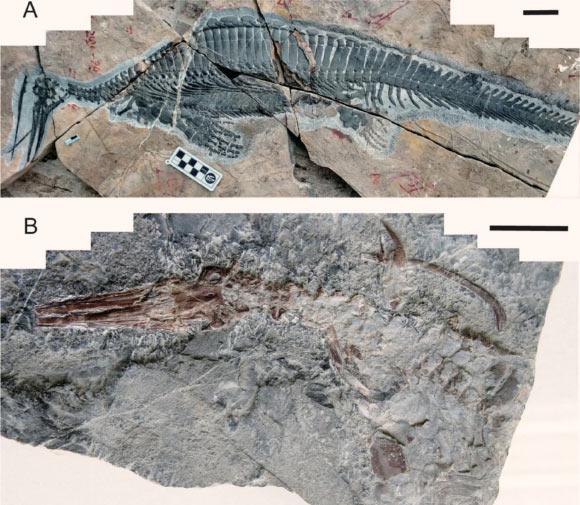

In their study, Dr. Fang and colleagues examined two specimens of Hupehsuchus nanchangensis, a hupehsuchian reptile from the Triassic period of China.

Both specimens were collected from the Jialingjiang Formation in Nanzhang and Yuan’an County, Hubei Province.

One specimen is well-preserved from head to clavicle (collarbone), while the other is a nearly complete skeleton.

“The hupehsuchians were a unique group in China, close relatives of the ichthyosaurs, and known for 50 years, but their mode of life was not fully understood,” Dr. Fang said.

“The hupesuchians lived in the Early Triassic, about 248 million years ago, in China and they were part of a huge and rapid re-population of the oceans,” added University of Bristol’s Professor Michael Benton.

“This was a time of turmoil, only 3 million years after the huge end-Permian mass extinction which had wiped out most of life.”

“It’s been amazing to discover how fast these large marine reptiles came on the scene and entirely changed marine ecosystems of the time.”

New specimens of Hupehsuchus nanchangensis. Scale bar – 5 cm. Image credit: Fang et al., doi: 10.1186/s12862-023-02143-9.

The authors compared the shape and dimensions of the Hupehsuchus nanchangensis skull to 130 skulls from different aquatic animals, including 15 species of baleen whale, 52 species of toothed whale, 23 seal species, 14 crocodilians, 25 bird species, and the platypus.

Hupehsuchus nanchangensis possessed an unusual, toothless snout with two long bones in the upper skull framing a narrow space.

It also had a narrow mandible (lower jaw) that was loosely connected to the rest of the skull and would have allowed it to expand its mouth cavity to accommodate large gulps of water.

While no evidence of baleen was found in the specimens, they possessed a series of grooves around the edge of the palate (roof of the mouth), which may have indicated the presence of soft tissues that could have played a similar role in filter feeding.

Hupehsuchus nanchangensis was likely a slow swimmer due to its rigid body, which suggests it might have fed in a style similar to that of a bowhead or right whale, which swim with their mouth open near the surface of the ocean in order to strain food from the water.

High levels of competition for food at this point in the Triassic may have caused Hupehsuchus nanchangensis to develop this specialized feeding method.

“We discovered two new hupehsuchian skulls,” said Professor Long Cheng, a researcher at the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey.

“These were more complete than earlier finds and showed that the long snout was composed of unfused, straplike bones, with a long space between them running the length of the snout.”

“This construction is only seen otherwise in modern baleen whales where the loose structure of the snout and lower jaws allows them to support a huge throat region that balloons out enormously as they swim forward, engulfing small prey.”

“The other clue came in the teeth… or the absence of teeth,” said Dr. Li Tian, a researcher at the University of Geosciences Wuhan.

“Modern baleen whales have no teeth, unlike the toothed whales such as dolphins and orcas.”

“Baleen whales have grooves along the jaws to support curtains of baleen, long thin strips of keratin, the protein that makes hair, feathers and fingernails.”

“Hupehsuchus nanchangensis had just the same grooves and notches along the edges of its jaws, and we suggest it had independently evolved into some form of baleen.”

A paper on the findings appears in the journal BMC Ecology and Evolution.

_____

ZC. Fang et al. 2023. First filter feeding in the Early Triassic: cranial morphological convergence between Hupehsuchus and baleen whales. BMC Ecol Evo 23, 36; doi: 10.1186/s12862-023-02143-9