Gaseous planets with helium-rich atmospheres may be common in our Galaxy, according to a new study accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal (arXiv.org preprint).

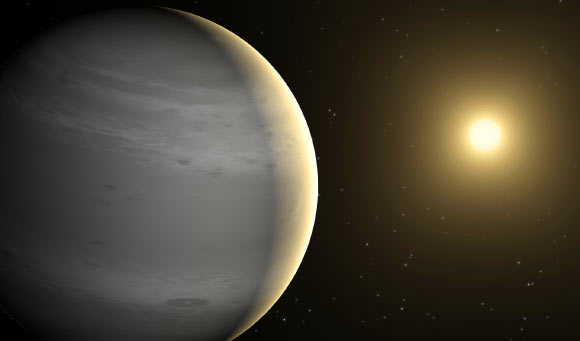

This artist’s concept depicts a proposed helium-atmosphere planet called Gliese 436b. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech.

To date, astronomers using NASA’s Kepler space telescope have discovered hundreds of candidate planets that fall into the category of the so-called warm Neptunes and sub-Neptunes.

These extrasolar gas giants would be around the mass of Neptune, or lighter, and would orbit close to their parent stars, basking in their searing heat.

According to the new study, radiation from the stars would boil off hydrogen in the atmospheres of the planets. Both hydrogen and helium are common ingredients of gas planets like these. Hydrogen is lighter than helium and thus more likely to escape.

After billions of years of losing hydrogen, the planet’s atmosphere would become enriched with helium.

“Hydrogen is about 4 times lighter than helium, so it would slowly disappear from the planets’ atmospheres, causing them to become more concentrated with helium over time. The process would be gradual, taking up to 10 billion years to complete,” said study lead author Dr Renyu Hu of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena.

Warm Neptunes and sub-Neptunes are thought to have either rocky or liquid cores, surrounded by gas. If helium is indeed the dominant component in their atmospheres, the planets would appear white or gray.

This is in contrast to Neptune, which is blue due to the presence of methane. Methane absorbs the color red, leaving blue. Neptune is far from our Sun and hasn’t lost its hydrogen. The hydrogen bonds with carbon to form methane.

This diagram illustrates how hypothetical helium atmospheres might form. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech.

A lack of methane in one particular warm Neptune, Gliese 436b, is in fact what led the astronomers to develop their helium planet theory. The planet, also known as GJ 436b, was discovered in August 2004. It’s located in the constellation Leo, approximately 33.4 light-years away.

NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope had previously observed Gliese 436b and found evidence for carbon but not methane. This was puzzling to astronomers, because methane molecules are made of one carbon and four hydrogen atoms, and planets like this are expected to have a lot of hydrogen.

According to the theory formulated by Dr Hu and co-authors, the hydrogen might have been slow-cooked off the planet by radiation from the host stars. With less hydrogen around, the carbon would pair up with oxygen to make carbon monoxide. In fact, NASA’s Spitzer found evidence for a predominance of carbon monoxide in the atmosphere of Gliese 436b.

The next step to test the theory is to look at other warm Neptunes and sub-Neptunes for signs of carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide, which are indicators of helium atmospheres.

_____

Renyu Hu et al. 2015. Helium Atmospheres on Warm Neptune- and Sub-Neptune-Sized Exoplanets and Applications to GJ 436 b. ApJ, accepted for publication; arXiv: 1505.02221