‘Lucy,’ perhaps the world’s most famous early human ancestor, probably died after falling from a tall tree, according to an international team of researchers led by University of Texas at Austin anthropologist John Kappelman.

Forensic facial reconstruction of Australopithecus afarensis. Image credit: Cicero Moraes / CC BY-SA 3.0.

“It is ironic that the fossil at the center of a debate about the role of arborealism in human evolution likely died from injuries suffered from a fall out of a tree,” Prof. Kappelman said.

Lucy, a 3.18-million-year-old specimen of Australopithecus afarensis, is among the oldest and most complete fossil hominin skeletons discovered.

The specimen was found by Arizona State University scientists Donald Johanson and Tom Gray on the November 24, 1974, at the site of Hadar in the Afar region of Ethiopia.

It is represented by elements of the skull, upper limb, hand, axial skeleton, pelvis, lower limb, and foot, with some bilateral preservation, and is popularly described as 40% complete.

Since her discovery, Lucy has been at the center of a debate about whether Australopithecus afarensis were frequent tree-climbers.

“Lucy is precious. There’s only one Lucy, and you want to study her as much as possible,” said co-author Prof. Richard Ketcham, also from the University of Texas at Austin.

Prof. Kappelman, Prof. Ketcham and their colleagues from the United States and Ethiopia studied the original fossil and computed tomographic (CT) scans of the skeleton to assess cause of death.

Studying the specimen and a digital archive of more than 35,000 images, they noticed something unusual: the end of Lucy’s right humerus was fractured in a manner not normally seen in fossils, preserving a series of sharp, clean breaks with tiny bone fragments and slivers still in place.

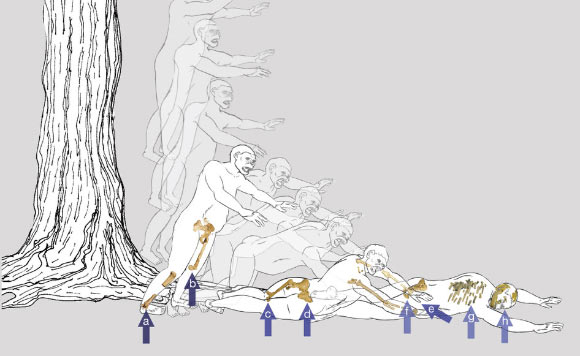

Reconstruction of Lucy’s vertical deceleration event. Kappelman et al hypothesize that Lucy fell from a tall tree, landing feet-first and twisting to the right, with arrows indicating the sequence and types of fractures: (a) pilon fracture, tibial plateau fracture, and spiral shaft fracture of right tibia; (b) the impact of hyperextended left knee drove the distal femoral epiphysis into the distal shaft, and fractured the femoral neck and possibly the acetabulum, sacrum, and lumbar vertebra; (c) the impact of the knee drove the patella into the centre anterodistal surface of the femoral shaft; (d) impact on the right hip drove the right innominate into the sacrum, and the sacrum into the left innominate, dislocating and fracturing the sacrum and left innominate, and elevating the retroauricular surface; (e) Lucy was still conscious when she stretched out her arms in an attempt to break her fall and fractured both proximal humeri, the right more severely than the left with spiral fracture near the midshaft, a Colles’ (or Smith’s) fracture of the right radius, and perhaps other fractures of the radii and ulnae; the impact depressed and retracted the right scapula, which depressed the clavicle into the first rib, fracturing both; (f) frontal impact fractured the left pubis and drove a portion of the anterior inferior pubic ramus posterolaterally, and a branch or rock possibly created the puncture mark on the pubis; (g) the impact of the thorax fractured many ribs and possibly some thoracic vertebrae; (h) the impact of the skull, slightly left of center, created a tripartite guardsman fracture of the mandible and cranial fractures. Image credit: John Kappelman et al, doi: 10.1038/nature19332.

“This compressive fracture results when the hand hits the ground during a fall, impacting the elements of the shoulder against one another to create a unique signature on the humerus,” Prof. Kappelman said.

“The injury was consistent with a four-part proximal humerus fracture, caused by a fall from considerable height when the conscious victim stretched out an arm in an attempt to break the fall,” said co-author Dr. Stephen Pearce, an orthopedic surgeon at Austin Bone and Joint Clinic.

The team observed similar but less severe fractures at the left shoulder and other compressive fractures throughout Lucy’s skeleton including a pilon fracture of the right ankle, a fractured left knee and pelvis, and even more subtle evidence such as a fractured first rib — all consistent with fractures caused by a fall.

Without any evidence of healing, the scientists concluded the breaks occurred perimortem, or near the time of death.

The question remained: how could Lucy have achieved the height necessary to produce such a high velocity fall and forceful impact?

“Because of her small size – about 3 feet 6 inches (1.1 m) and 64 pounds (29 kg) – Lucy probably foraged and sought nightly refuge in trees,” Prof. Kappelman said.

In comparing her with chimpanzees, he suggested Lucy probably fell from a height of more than 40 feet (12.2 m), hitting the ground at more than 35 mph (56 km per hour).

Based on the pattern of breaks, Prof. Kappelman hypothesized that Lucy landed feet-first before bracing herself with her arms when falling forward, and ‘death followed swiftly.’

“When the extent of Lucy’s multiple injuries first came into focus, her image popped into my mind’s eye, and I felt a jump of empathy across time and space,” he said.

“Lucy was no longer simply a box of bones but in death became a real individual: a small, broken body lying helpless at the bottom of a tree.”

Prof. Kappelman conjectured that because Lucy was both terrestrial and arboreal, features that permitted her to move efficiently on the ground may have compromised her ability to climb trees, predisposing her species to more frequent falls.

The team’s findings were published online this week in the journal Nature.

_____

John Kappelman et al. Perimortem fractures in Lucy suggest mortality from fall out of tall tree. Nature, published online August 29, 2016; doi: 10.1038/nature19332