A large, multinational team of scientists has discovered a previously-unknown species of extinct hominin in the Rising Star cave, Cradle of Humankind, South Africa. Besides shedding light on the origins and diversity of the genus Homo, the new species — named Homo naledi — also appears to have intentionally deposited bodies of its dead in the cave chamber, a behavior previously thought limited to humans.

A reconstruction of Homo naledi’s head by paleoartist John Gurche, who spent some 700 hours recreating the head from bone scans. The find was announced by the University of the Witwatersrand, the National Geographic Society and the South African National Research Foundation and published in the journal eLife. Image credit: John Gurche / Mark Thiessen / National Geographic.

Consisting of 1,550 numbered fossil elements, the discovery is the single largest fossil hominin find yet made on the continent of Africa.

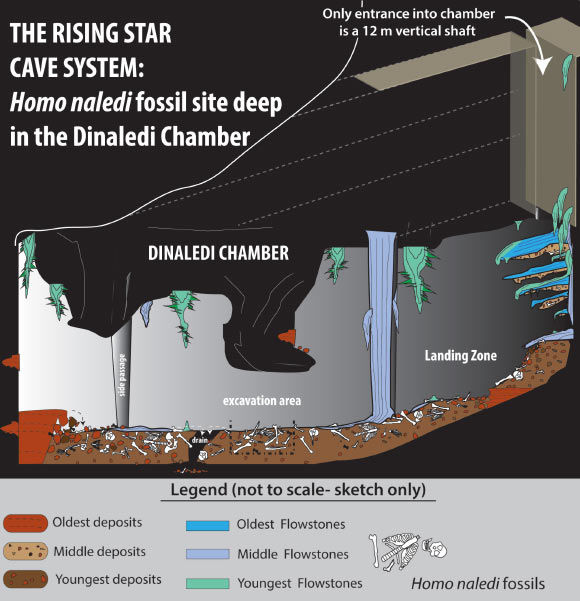

The initial discovery was made two years ago in the Dinaledi Chamber (Chamber of Stars) of the Rising Star cave by South Africa’s Wits University scientists and volunteer cavers. The cave is located near what is called the Cradle of Humankind, a World Heritage Site in Gauteng province well known for critical discoveries of early humans, including the 1947 discovery of 2.3 million-year-old Australopithecus africanus.

Homo naledi was named after the Rising Star cave – naledi means ‘star’ in Sesotho, a South African language.

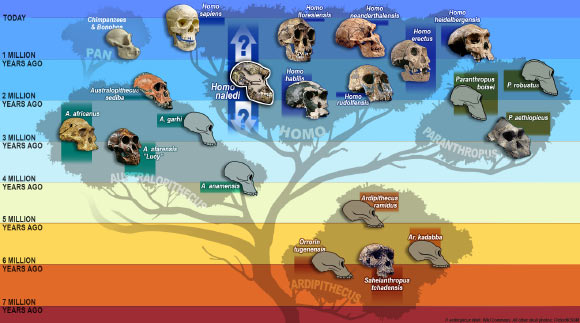

While the fossils of Homo naledi have yet to be dated, the species may have been a contemporary of Homo sapiens 100,000 years ago – or it may be far older. Image credit: S. V. Medaris / UW-Madison.

So far, parts of at least 15 skeletons representing individuals of all ages have been found and scientists believe many more fossils remain in the chamber.

The fossils, which have yet to be dated, laid about 295 feet (90 m) from the cave entrance, accessible only through a chute so narrow that a special team of very slender individuals was needed to retrieve them.

“The fossils have yet to be dated. The unmineralized condition of the bones and the geology of the cave have prevented an accurate dating,” said Dr John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“They could have been there 2 million years ago or 100,000 years ago, possibly coexisting with modern humans. We don’t yet have a date, but we’re attempting it in every way we can.”

“If it turns out that Homo naledi is old, say older than around 2-million-years, it would represent the earliest appearance of Homo that is based on more than just an isolated fragment,” Dr Hawks and his colleagues said.

“On the other hand, if it turns out that Homo naledi is young, say less than 1-million-years old, it would demonstrate that several different types of ancient humans all existed at the same time in southern Africa, including an especially small-brained form like Homo naledi.”

“With almost every bone in the body represented multiple times, Homo naledi is already practically the best-known fossil member of our lineage,” said Prof Lee Berger of Wits University.

“The unusual combination of characters that we see in the Homo naledi skulls and skeletons is unlike anything that we have seen in any other early hominin species,” the scientists said. “It shares some features with australopiths (like Sediba, Lucy, Mrs Ples and the Taung Child), some features with Homo, and shows some features that are unique to it, thus it represents something entirely new to science.”

“The features of Homo naledi are similar to other early hominids, combining a human-like face, feet and hands, but with a short, ape-like torso and a very small brain,” said Prof Paul Dirks of James Cook University.

“It is a mixture of primitive features and evolved features. It shows there were different species of hominids alive at different times that combined all sorts of different features. Nature was experimenting.”

“Overall, Homo naledi looks like one of the most primitive members of our genus, but it also has some surprisingly human – like features, enough to warrant placing it in the genus Homo,” Dr Hawks said.

“The species had a tiny brain, about the size of an average orange (about 500 cubic cm), perched atop a very slender body.”

Homo naledi stood approximately 5 feet (1.5 m) tall and weighed about 45 kg. Its teeth are described as similar to those of the earliest-known members of our genus, such as Homo habilis, as are most features of the skull. The shoulders, however, are more similar to those of apes.

“The hands suggest tool-using capabilities. Surprisingly, Homo naledi has extremely curved fingers, more curved than almost any other species of early hominin, which clearly demonstrates climbing capabilities,” said Dr Tracy Kivell of the University of Kent, UK.

“This contrasts with the feet of the species, which are virtually indistinguishable from those of modern humans,” added Dr William Harcourt-Smith of Lehman College, City University of New York, and the American Museum of Natural History.

Its feet, combined with its long legs, suggest that the species was well-suited for long-distance walking.

“The combination of anatomical features in Homo naledi distinguishes it from any previously known species,” Dr Berger said.

Perhaps most remarkably, the context of the find has led the team to conclude that this primitive-looking hominin may have practiced a form of behavior previously thought to be unique to humans.

The Dinaledi Chamber has “always been isolated from other chambers and never been open directly to the surface. What’s important for people to understand is that the remains were found practically alone in this remote chamber in the absence of any other major fossil animals,” Prof Dirks said.

“So remote was the space that out of more than 1,500 fossil elements recovered, only about a dozen are not hominin, and these few pieces are isolated mouse and bird remains, meaning that the chamber attracted few accidental visitors. Such a situation is unprecedented in the fossil hominin record,” Dr Hawks said.

The researchers note that the bones bear no marks of scavengers or carnivores or any other signs that non-hominin agents or natural processes, such as moving water, carried these individuals into the chamber.

“We explored every alternative scenario, including mass death, an unknown carnivore, water transport from another location, or accidental death in a death trap, among others. In examining every other option, we were left with intentional body disposal by Homo naledi as the most plausible scenario,” Dr Berger said.

This suggests the possibility of a form of ritualized behavior previously thought to be unique to humans.

The finds are described in two papers (paper 1 & paper 2) published online in the open-access journal eLife and reported in the cover story of the October issue of National Geographic magazine.

_____

Lee R Berger et al. 2015. Homo naledi, a new species of the genus Homo from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa. eLife 4: e09560; doi: 10.7554/eLife.09560

Paul HGM Dirks et al. 2015. Geological and taphonomic context for the new hominin species Homo naledi from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa. eLife 4: e09561; doi: 10.7554/eLife.09561