Homo naledi – an extinct species of hominin whose fossil skeletons were discovered in a South African cave and introduced to the world last month – may have been uniquely adapted for both tree climbing and walking as dominant forms of movement, while also being capable of precise manual manipulation, according to two new studies published in the journal Nature Communications.

A reconstruction of Homo naledi’s head by paleoartist John Gurche, who spent some 700 hours recreating the head from bone scans. Image credit: John Gurche / Mark Thiessen / National Geographic.

One of the studies, titled The foot of Homo naledi, suggests that although its feet were the most human-like part of its body, Homo naledi didn’t use them to walk in the same way we do.

Lead author Dr William Harcourt-Smith of CUNY’s Lehman College and the American Museum of Natural History and his co-authors describe the Homo naledi foot based on 107 foot elements from the Dinaledi Chamber (Chamber of Stars) of the Rising Star cave, including a well preserved adult right foot.

They show the Homo naledi foot shares many features with a modern human foot, indicating it is well-adapted for standing and walking on two feet.

“However, it differs in having more curved toe bones (proximal phalanges),” the scientists said.

“Homo naledi’s foot is far more advanced than other parts of its body, for instance, its shoulders, skull, or pelvis,” Dr Harcourt-Smith said.

“Quite obviously, having a very human-like foot was advantageous to this creature because it was the foot that lost its primitive, or ape-like, features first. That can tell us a great deal in terms of the selective pressures this species was facing,” he said.

“This species has a unique combination of traits below the neck, and that adds another type of bipedalism to our record of human evolution.”

Because the Homo naledi fossils have not yet been dated, scientists don’t know how this form of bipedalism fits into our family tree.

“Regardless of age, this species is going to cause a paradigm shift in the way we think about human evolution, not only in the behavioral implications, but in morphological and anatomical terms,” Dr Harcourt-Smith said.

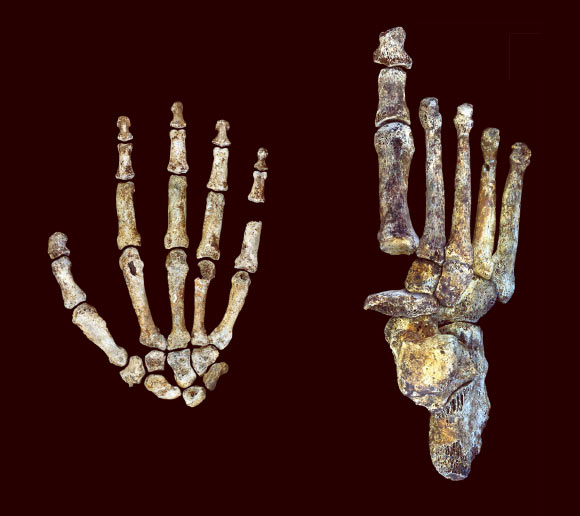

The Homo naledi hand and foot were uniquely adapted for both tree climbing and walking upright. Image credit: Peter Schmid / William Harcourt-Smith / Wits University.

Dr Tracey Kivell from the University of Kent, the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and the University of the Witwatersrand, led the second study, titled The hand of Homo naledi.

Dr Kivell and co-authors describe the Homo naledi hand based on nearly 150 hand bones, including a nearly complete adult right hand (missing only one wrist bone) of a single individual, which is a rare find in the human fossil record.

The hand of Homo naledi reveals a unique combination of anatomy that has not been found in any other fossil human before. The wrist bones and thumb show anatomical features that are shared with Neanderthals and humans and suggest powerful grasping and the ability to use stone tools.

However, the finger bones are more curved than most early fossil human species, such as Australopithecus afarensis, suggesting that Homo naledi still used their hands for climbing in the trees.

This mix of human-like features in combination with more primitive features demonstrates that the Homo naledi hand was both specialized for complex tool-use activities, but still used for climbing locomotion.

“The tool-using features of the Homo naledi hand in combination with its small brain size has interesting implications for what cognitive requirements might be needed to make and use tools, and, depending on the age of these fossils, who might have made the stone tools that we find in South Africa,” Dr Kivell explained.

_____

W.E.H. Harcourt-Smith et al. 2015. The foot of Homo naledi. Nature Communications 6, article number: 8432; doi: 10.1038/ncomms9432

Tracy L. Kivell et al. 2015. The hand of Homo naledi. Nature Communications 6, article number: 8431; doi: 10.1038/ncomms9431