A new analysis of the Cretaceous fossil Dinilysia patagonica is helping paleontologists solve an old scientific puzzle – how ancient snakes lost their limbs.

Artist’s restoration of Dinilysia patagonica. Image credit: Nobu Tamura, spinops.blogspot.com / CC BY-SA 3.0.

The new findings, described in the journal Science Advances, show snakes did not lose their limbs in order to live in the sea, as was previously suggested.

“How snakes lost their legs has long been a mystery to scientists, but it seems that this happened when their ancestors became adept at burrowing,” explained Dr Hongyu Yi of the University of Edinburgh, UK.

Dr Yi and his colleague, Dr Mark Norell from the American Museum of Natural History, used CT scans to examine the bony inner ear of Dinilysia patagonica.

“We hypothesize that Dinilysia patagonica was a burrower and that crown snakes originated from burrowing ancestors. For an ecomorphic indicator for snake habits, we used the shape of the inner ear instead of anatomical features that are not often preserved in fossils,” they said.

The bony canals and cavities of Dinilysia patagonica, like those in the ears of modern burrowing snakes, controlled its hearing and balance.

The scientists built 3D virtual models to compare the inner ears of the fossils with those of modern lizards and snakes.

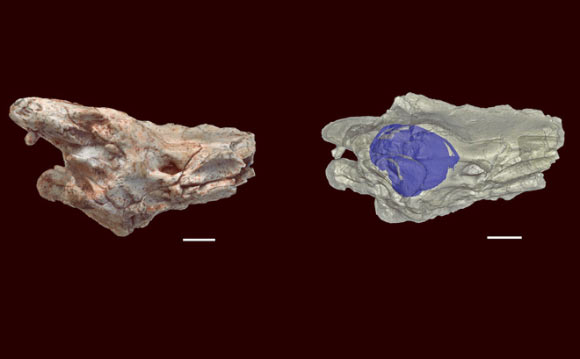

The braincase and inner ear of Dinilysia patagonica. Left: braincase of D. patagonica, showing the right otic region in lateral view. Right: X-ray CT model of the fossil, with the inner ear highlighted in blue. Scale bars – 5 mm. Image credit: Hongyu Yi / Mark A. Norell.

They found a distinctive structure within the inner ear of animals that actively burrow, which may help them detect prey and predators. This shape was not present in modern snakes that live in water or above ground.

“A burrowing life-style predated modern snakes, but it remained as the main, if not exclusive, habit for basal lineages among crown snakes,” Dr Yi and Dr Norell said.

“Both Dinilysia patagonica and the hypothetical ancestor of crown snakes have a large vestibule that is associated with low-frequency hearing. This suggests that ancestrally, crown snakes were able to detect prey and predator via substrate vibrations.”

The findings help paleontologists fill gaps in the story of snake evolution, and confirm Dinilysia patagonica as the largest burrowing snake ever known.

“With a snout-tail length exceeding 1.8 m, Dinilysia patagonica is the largest known burrowing snake, living or extinct,” the paleontologists said.

The findings also offer clues about a hypothetical ancestral species from which all modern snakes descended.

_____

Hongyu Yi & Mark A. Norell. 2015. The burrowing origin of modern snakes. Science Advances, vol. 1, no. 10, e1500743; doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500743