Acoustic communication has played a key role in the evolution of a wide variety of vertebrates and insects. However, the reconstruction of ancient acoustic signals is challenging due to the extreme rarity of fossilized organs. In new research, paleontologists from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology and Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and elsewhere analyzed the earliest tympanal ears and sound-producing systems (stridulatory apparatus) found in exceptionally preserved Mesozoic katydids. Their results show that katydids are the earliest known animals to have evolved complex acoustic communication, acoustic niche partitioning, and high-frequency musical calls.

Ecological restoration of singing katydids from the Middle Jurassic Daohugou Konservat-Lagerstätte of China. Image credit: Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology and Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The production of acoustic signals is one of the most important behavioral adaptions in animal communication, and the sending and receiving messages using sound is essential for the survival and success of many animals.

Acoustic communication can be defined as the transmission of messages via airborne sound waves and is enabled by specialized hearing and sound-producing organs.

It is widespread in two disparate extant animal groups: insects and vertebrates, the latter including frogs, reptiles, birds, and mammals.

Insects were the first terrestrial animals to use air-borne sound signals for long-distance communication. They display an extremely high diversity of auditory systems and sound-producing organs.

For example, tympanal ears have evolved at least 18 times independently in diverse species of seven living insect orders, involving at least 15 body locations.

Among acoustically signaling insects, katydids stand out as an ideal model to investigate the evolution of acoustic organs and behavior.

Male katydids produce sounds through friction between specialized veins of the forewings, and these sounds are received by males and females primarily through the ears.

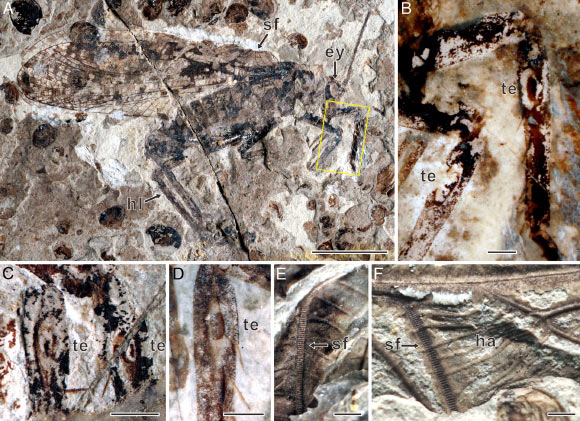

Prophalangopsid and haglid katydids from the Jurassic Daohugou Konservat-Lagerstätte of China. Scale bars – 10 mm in (A), 1 mm in (B-F). Image credit: Xu et al., doi: 10.1073/pnas.2210601119.

In the new study, Chunpeng Xu and colleagues found well-preserved tympanal ears in 24 prophalangopsid katydids from the Middle Jurassic Daohugou Konservat-Lagerstätte, consisting of four males in two genera and two species, 19 females in three genera, and one sex unknown.

They also examined the sound-producing and sound-radiating systems of forewings in 87 specimens of 31 genera and 40 species from the Middle/Late Triassic of Kyrgyzstan, Late Triassic of South Africa, and Middle Jurassic Daohugou Konservat-Lagerstätte of China.

“The newly found tympanal ears in prophalangopsid katydids from the Middle Jurassic Daohugou Konservat-Lagerstätte represent the earliest-known insect ears, extending the age range of the modern-type auditory tympana by 100 million years to the Middle Jurassic, some 160 million years ago,” Xu said.

“The reconstruction of singing frequencies of Mesozoic katydids and oldest tympanal ears demonstrate that katydids had evolved complex acoustic communication, including mating signals, inter-male communication, and directional hearing, at least by the Middle Jurassic.”

“Also, katydids had evolved a high diversity of singing frequencies, including high-frequency musical calls, accompanied by acoustic niche partitioning, all at least by the Late Triassic (200 million years ago).”

“This suggests that acoustic communication already could have been an important evolutionary driver in the early radiation of terrestrial insects after the Permo-Triassic mass extinction.”

“The Early and Middle Jurassic katydid transition from extinct haglid- to extant prophalangopsid-dominated insect faunas coincided with the diversification of derived mammalian groups and improvement of hearing in early mammals, supporting the hypothesis of acoustic co-evolution of mammals and katydids.”

According to the team, the high-frequency songs of Mesozoic katydids could even have driven the evolution of intricate hearing systems in early mammals, and conversely, mammals with progressive hearing ability could have exerted selective pressure on the evolution of katydids, including faunal turnover.

“These findings demonstrate that insects, especially katydids, dominated choruses during the Triassic — a situation different from the modern soundscape,” the researchers said.

“After the appearance of birds and frogs in the Jurassic, the forest soundscape became almost the same as the modern one in the Cretaceous, except lacking the sound of cicadas (which have fewer musical calls).”

“These results also highlight the ecological significance of insects in the Mesozoic soundscape, which has hitherto been largely unknown in the palaeontological record.”

The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

_____

Chunpeng Xu et al. 2023. High acoustic diversity and behavioral complexity of katydids in the Mesozoic soundscape. PNAS 119 (51): e2210601119; doi: 10.1073/pnas.2210601119