Now known for its sports teams, Harleys, and beer, early Milwaukee County, Wisconsin was one of the nation’s leading producers of natural cement, and the fossils from its cement mines revealed one of the country’s most diverse assemblages of animals and plants of their age (Middle Devonian, ~385 million years ago). With the depletion of the cement rock, so went the ‘era of discovery’ of those fossils, but the few remaining exposures have become an important Geoheritage site, and museum collections still house many thousands of fossils that can be prepared and used for research, display, and educational purposes.

The giant fungus, Prototaxites milwaukeensis, MPM Pb402. Scale bar – 10 cm. Image credit: Kenneth C. Gass / CC BY-SA 4.0.

From 1876 to 1911 rock obtained from the Middle Devonian (~385 million years ago) Milwaukee Formation produced not only much of the country’s natural cement, but many thousands of fossils from a wide variety of environmental settings, representing around 250 species, 100 families, 16 phyla, and four kingdoms.

This remarkably large number of taxa, some known from only a few specimens, is attributed to unusually intense collecting by amateur and professional geologists, and to a greater extent, numerous quarry workers who were paid by wealthy amateurs for their best fossils.

Had other Middle Devonian occurrences been collected this intensely, some may have yielded similar results.

Although the fossils were preserved in marine sediments, some plants, trees and giant fungi were washed into the sea after living in terrestrial environments, buried in the sediment, and fossilized along with the marine individuals.

The biota also has the distinction of producing Eastmanosteus pustulosus (the type species of that fearsome placoderm fish genus), some of the first trees (lycopsids and possible cladoxylopsids), and fossils of the rare tree-sized fungus, Prototaxites — the largest organism on land when it first appeared earlier in the Devonian.

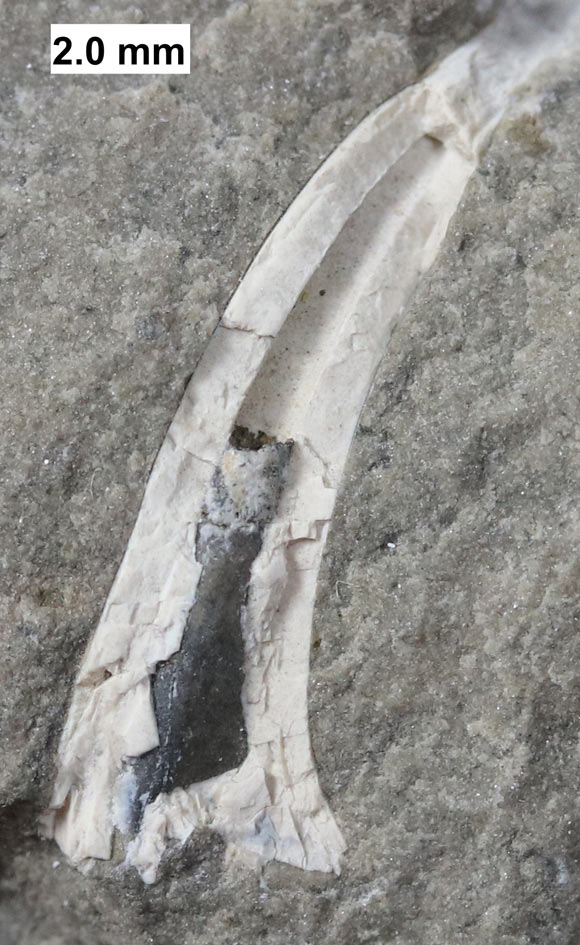

Also of significance are occasional occurrences of exceptional preservation, such as the sarcopterygian (lobe-finned fish) tooth that retains coalified pulp in its pulp chamber.

Tooth from the sarcopterygian fish, Onychodus, showing coalified pulp in the pulp chamber, MPM VP477. Image credit: Kenneth C. Gass / CC BY-SA 4.0.

These strata also preserve color patterns on some of the skeletal material, such as the shells of certain brachiopod species, and the fin spines of certain placoderms. Such occurrences are rather rare in the fossil record.

Additionally, the majority of the Milwaukee Formation’s fossils are encrusted by numerous epibionts, including agglutinated foraminifers, tabulate corals, bryozoans, hederelloids, craniiform and linguliform brachiopods, microconchids, and edrioasteroids.

Milwaukee Public Museum paleontologist Kenneth Gass discussed this occurrence in relation to Geoheritage in his new paper published in a Geological Society of London Special Publication.

Although most of the strata are gone or no longer accessible, the type locality still contains exposed strata.

Because it is the type locality and located in county parks where removing material is not permitted, fossil collecting is prohibited.

The linguliform brachiopod, Barroisella? milwaukeensis, showing color patterns, MPM P236. Image credit: Kenneth C. Gass / CC BY-SA 4.0 International.

“The strata can still be used for educational and non-destructive research purposes,” Gass said.

Also, large collections, such as those housed in the Milwaukee Public Museum, the Greene Geological Museum (UW-Milwaukee), the Smithsonian Institution, and the Museum of Comparative Zoology, are preserved for further study and display.

But the collecting method used to accumulate most of these fossils had a down-side: it lacked measures to assure that the fossils were traceable to their exact location and stratigraphic placement.

“Any data not documented is lost and irretrievable,” Gass cautioned.

“This teaches us that, before doing fieldwork on a significant geological site, all collectors should be trained on the importance of documenting the exact locality, stratigraphic placement, and other important data for each fossil.”

_____

Kenneth C. Gass. 2023. The Milwaukee Formation (Givetian, Wisconsin): gone but not forgotten. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 543; doi: 10.1144/SP543-2022-1