Biologists, reporting in the open-access journal PLoS ONE, have identified more than 180 species of biofluorescent fishes. Their study shows that biofluorescence is common and variable among marine fish species, indicating its potential use in communication and mating.

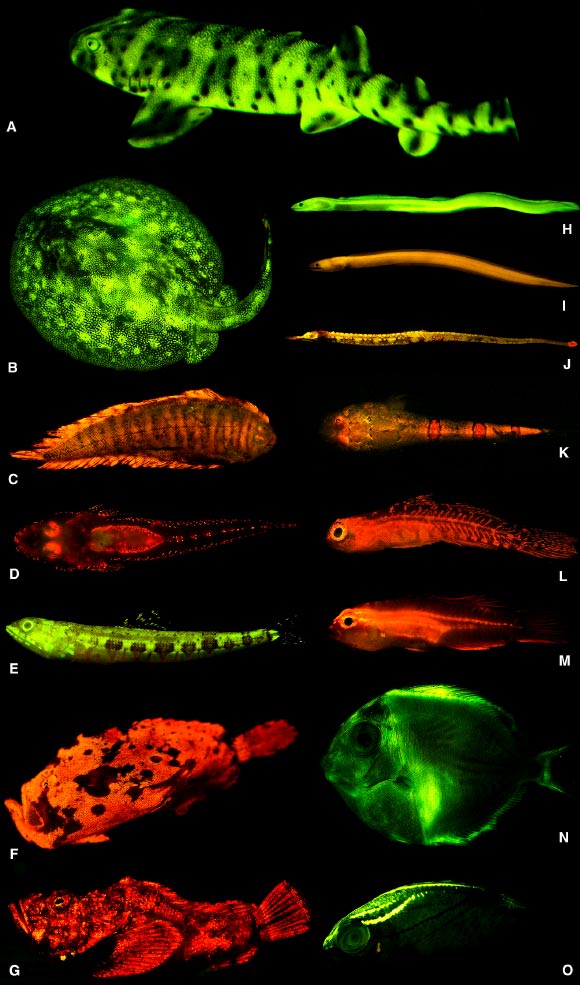

This image shows biofluorescent fishes: A – the Swellshark, Cephaloscyllium ventriosum; B – the Yellow stingray, Urobatis jamaicensis; C – the Blue Edged Sole, Soleichthys heterorhinos; D – the Brownmargin flathead, Cociella hutchinsi; E – the Variegated lizardfish, Synodus dermatogenys; F – the Warty frogfish, Antennarius maculatus; G – the False stonefish; H – the Shortfin moray eel, Kaupichthys brachychirus; I – the Collared eel, Kaupichthys nuchalis; J – the Messmate pipefish, Corythoichthys haematopterus; K – the Warteye stargazer, Gillellus uranidea; L – goby, Eviota sp.; M – the Blackbelly Dwarfgoby, Eviota atriventris; N – the Blue tang surgeonfish, Acanthurus coeruleus, larval; O – the Two-lined monocle bream, Scolopsis bilineata.

Biofluorescence is a phenomenon by which organisms absorb light, transform it, and eject it as a different color.

To explore this phenomenon, the scientists embarked on five high-tech expeditions to tropical waters off of Little Cayman Island, the Bahamas and the Solomon Islands.

During night dives, they stimulated biofluorescence in the fish with high-intensity blue light arrays housed in watertight cases.

The resulting underwater light show is invisible to the human eye. To record this activity, they used custom-built underwater cameras with yellow filters, which block out the blue light, as well as yellow head visors that allow them to see the biofluorescent glow while swimming on the reef.

“We’ve long known about biofluorescence underwater in organisms like corals, jellyfish, and even in land animals like butterflies and parrots, but fish biofluorescence has been reported in only a few research publications,” explained study lead author Dr John Sparks from the American Museum of Natural History.

Unlike the full-color environment that humans and other terrestrial animals inhabit, fishes live in a world that is predominantly blue because, with depth, water quickly absorbs the majority of the visible light spectrum.

“By designing scientific lighting that mimics the ocean’s light along with cameras that can capture the animals’ fluorescent light, we can now catch a glimpse of this hidden biofluorescent universe,” said senior author Dr David Gruber from both Baruch College and the American Museum of Natural History.

“Many shallow reef inhabitants and fish have the capabilities to detect fluorescent light and may be using biofluorescence in similar fashions to how animals use bioluminescence, such as to find mates and to camouflage.”

The expeditions revealed a zoo of biofluorescent fishes – from both cartilaginous and bony fishes – especially among cryptically patterned, well-camouflaged species living in coral reefs.

By imaging and collecting specimens in the island waters, and conducting supplementary studies at public aquariums after hours, the team identified more than 180 species of biofluorescent fishes, including species-specific emission patterns among close relatives.

______

Sparks JS et al. 2014. The Covert World of Fish Biofluorescence: A Phylogenetically Widespread and Phenotypically Variable Phenomenon. PLoS ONE 9 (1): e83259; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083259