It has often been claimed that we learn language using brain circuits that are specifically dedicated to this purpose. Now, new evidence suggests that language — indeed both first and second language — is learned in circuits that also are used for many other purposes and even pre-existed Homo sapiens.

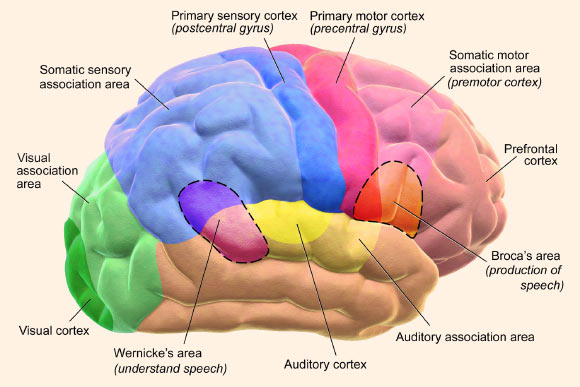

According to Hamrick et al, language is learned, in specific ways, by general-purpose neurocognitive mechanisms that pre-exist Homo sapiens. This image shows functional areas of the human brain; dashed areas shown are commonly left hemisphere dominant. Image credit: Blausen.com staff, doi: 10.15347/wjm/2014.010.

“Our conclusion that language is learned in such ancient general-purpose brain systems contrasts with the long-standing theory that language depends on innately-specified language modules found only in humans,” said Professor Michael Ullman, a neuroscientist at Georgetown University School of Medicine and senior author of a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“These brain systems are also found in animals — for example, rats use them when they learn to navigate a maze,” added co-author Dr. Phillip Hamrick, of Kent State University.

“Whatever changes these systems might have undergone to support language, the fact that they play an important role in this critical human ability is quite remarkable.”

The research has important implications not only for understanding the biology and evolution of language and how it is learned, but also for how language learning can be improved, both for people learning a foreign language and for those with language disorders such as autism, dyslexia, or aphasia.

“Our findings have broad research, educational, and clinical implications,” said co-author Dr. Jarrad Lum, from Deakin University in Australia.

The authors statistically synthesized findings from 16 studies that examined language learning in two well-studied brain systems: declarative and procedural memory.

The results showed that how good we are at remembering the words of a language correlates with how good we are at learning in declarative memory, which we use to memorize shopping lists or to remember the bus driver’s face or what we ate for dinner last night.

Grammar abilities, which allow us to combine words into sentences according to the rules of a language, showed a different pattern.

The grammar abilities of children acquiring their native language correlated most strongly with learning in procedural memory, which we use to learn tasks such as driving, riding a bicycle, or playing a musical instrument.

In adults learning a foreign language, however, grammar correlated with declarative memory at earlier stages of language learning, but with procedural memory at later stages.

The correlations were large, and were found consistently across languages (e.g., English, French, Finnish, and Japanese) and tasks (e.g., reading, listening, and speaking tasks), suggesting that the links between language and the brain systems are robust and reliable.

“Researchers still know very little about the genetic and biological bases of language learning, and the new findings may lead to advances in these areas,” Professor Ullman said.

“We know much more about the genetics and biology of the brain systems than about these same aspects of language learning.”

“Since our results suggest that language learning depends on the brain systems, the genetics, biology, and learning mechanisms of these systems may very well also hold for language.”

_____

Phillip Hamrick et al. Child first language and adult second language are both tied to general-purpose learning systems. PNAS, published ahead of print January 29, 2018; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1713975115