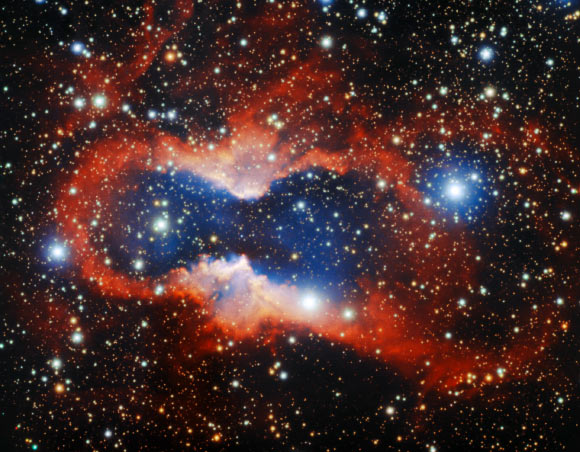

Astronomers using the Gemini South telescope on the summit of Cerro Pachon in Chile have taken a picture of CVMP 1, a planetary nebula located some 6,500 light-years away in the southern constellation of Circinus. Also known as PN G321.6+02.2 and Marsalkova 252, this object emerged when an old red giant star blew off its outer layers in the form of a tempestuous stellar wind. As this cast-aside stellar atmosphere sped outwards into interstellar space, the hot, exposed core of the progenitor star began to energize the ejected gases and cause them to glow.

This image, taken by the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrograph on the Gemini South telescope on Cerro Pachón in Chile, shows the planetary nebula CVMP 1. Image credit: Gemini Observatory / NSF’s National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory / AURA.

Planetary nebulae like CVMP 1 are formed by only certain stars — those with a mass somewhere between 0.8 and 8 times that of our Sun.

Less massive stars will gently fizzle out, transitioning into white dwarfs at the end of their long lives, whereas more massive stars live fast and die young, ending their lives in gargantuan explosions known as supernovae.

For stars lying between these extremes, however, the final stretch of their lives results in a striking astronomical display such as the one seen in this image.

Unfortunately, the spectacle provided by a planetary nebula is as brief as it is glorious. These objects typically persist for only 10,000 years — a tiny stretch of time compared to the lifespan of most stars, which lasts billions of years.

These short-lived planetary nebulae come in myriad shapes and sizes, and several particularly striking forms are well known, such as the Helix Nebula.

The great diversity of shapes stems from the diversity of progenitor star systems, whose characteristics can greatly influence the ensuing planetary nebula.

The presence of companion stars, orbiting planets, or even the rotation of the original red giant star can help determine the shape of a planetary nebula, but we don’t yet have a detailed understanding of the processes sculpting these beautiful astronomical fireworks displays.

But CVMP 1 is intriguing for more than just its aesthetic value: CVMP 1 is one of the largest planetary nebulae known; the gases making up the hourglass are highly enriched with helium and nitrogen.

These clues together suggest that CVMP 1 is highly evolved, making it an ideal object to help astronomers understand the later lives of planetary nebulae.

By measuring the light emitted from the gas in the planetary nebula, astronomers infer that the temperature of CVMP 1’s central star is at least 130,000 degrees Celsius (230,000 degrees Fahrenheit).

Despite this scorching temperature, the star is doomed to steadily cool over thousands of years.

Eventually, the light it emits will have too little energy to ionize gas in the planetary nebula, causing the striking hourglass shown in this image to fade from view.