A multinational group of astronomers has discovered a distant cluster of galaxies with active star formation occurring in close proximity to the cluster’s central galaxy. The discovery is the first to show that galaxies at the cores of massive clusters can grow significantly by feeding off gas stolen from other galaxies.

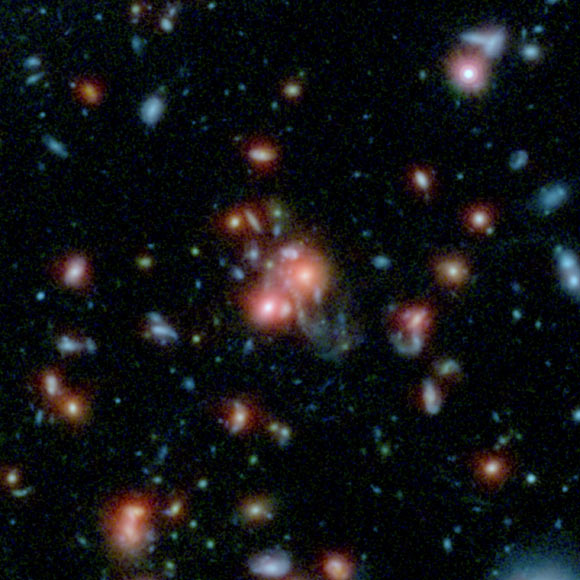

This image, using data from Spitzer and the Hubble Space Telescope, shows the galaxy cluster SpARCS1049+56. At the middle of the picture is the largest, central member of the family of galaxies (upper right red dot of central pair). Unlike other central galaxies in clusters, this one is bursting with the birth of new stars. Image credit: NASA / STScI / ESA / JPL-Caltech / McGill.

The galaxy cluster in question, named SpARCS104922.6+564032.5 (SpARCS1049+56), contains at least 27 galaxies and has a total mass equal to about 400 trillion Suns.

It is located in the Ursa Major constellation and is so far away that its light took 9.8 billion years to reach us.

SpARCS1049+56 was initially discovered using NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope and the Canada-France-Hawaii telescope, and confirmed using the W.M. Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea.

Galaxy clusters are vast families of galaxies bound together by gravity. Our Milky Way Galaxy resides within a small galaxy group known as the Local Group, which itself is a member of the massive Laniakea supercluster.

Galaxies at the centers of clusters are usually made of stellar fossils – old, red or dead stars. However, a giant galaxy at the heart of SpARCS1049+56 seems to be bucking the trend, instead forming new stars at an incredible rate.

“We think the giant galaxy at the centre of SpARCS1049+56 is furiously making new stars after merging with a smaller galaxy,” said Dr Tracy Webb of McGill University, who is the lead author of a paper published in the Astrophysical Journal.

“It is very exciting to have discovered such an interesting object. Understanding its nature proved to be a real scientific challenge which required the combined efforts of an international team of astronomers and many of the world’s best telescopes to solve,” said co-author Prof Gillian Wilson of the University of California, Riverside.

“What is so unusual about this cluster is that it is forming stars at a prodigious rate, more than 800 solar masses per year. To put that in perspective, our own galaxy, the Milky Way, is forming stars at the rate of only about one solar mass per year.”

Co-author Dr Jason Surace of NASA’s Spitzer Science Center added: “with Spitzer’s infrared camera, we can actually see the ferocious heat from all these hot young stars.”

Follow-up studies with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope in visible light helped confirm the source of the fuel, or gas, for the new stars.

Hubble detected features in the smaller, merging galaxy called ‘beads on a string,’ which are pockets of gas that condense where new stars are forming.

Beads on a string are telltale signs of collisions between gas-rich galaxies, a phenomenon known to astronomers as wet mergers, where ‘wet’ refers to the presence of gas. In these smash-ups, the gas is quickly converted to new stars.

Dry mergers, by contrast, occur when galaxies with little gas collide and no new stars are formed.

Typically, galaxies at the centers of clusters grow in mass through dry mergers at their core, or by siphoning gas into their centers. The new discovery is one of the only known cases of a wet merger at the core of a galaxy cluster, and the most distant example ever found.

The astronomers now aim to explore how common this type of growth mechanism is in clusters of galaxies.

_____

Tracy Webb et al. 2015. An extreme starburst in the core of a rich galaxy cluster at z = 1.7. ApJ 809, 173; doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/809/2/173