A rare species of orangutan, a majestic tree, a beetle that looks like part of an ant, the world’s deepest-living fish, and the fossil of a marsupial lion that lived in Australia in the Oligocene and Miocene epochs are among the 10 most amazing species chosen by experts at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry (ESF) from over 18,000 species new to science in 2017.

ESF releases the top 10 list each year in conjunction with the May 23 birthday of Carolus Linnaeus, an 18th century Swedish botanist who is considered the ‘Father of Taxonomy.’

His work in the mid-18th century was the beginning point for ‘modern’ naming and classification of plants and animals.

1. The Tapanuli orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis), a species of great ape from the Indonesian island of Sumatra:

The Tapanuli orangutan is one of three known species of orangutan, alongside the Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii) and the Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus).

Genomic evidence suggests that while the northern Sumatra and Borneo species separated about 674 thousand years ago, the Tapanuli species diverged much earlier, about 3.38 million years ago.

Only an estimated 800 individuals of the Tapanuli orangutan exist in fragmented habitat spread over about 250,000 acres (about 1,000 km2) on medium elevation hills and submontane forests from about 1,000 to 4,000 feet (300 to 1,300 m) above sea level, with densest populations in primary forest.

2. Wakaleo schouteni, a species of carnivorous marsupial lion that lived 26 to 18 million years ago (late Oligocene to early Miocene) in Australia’s rainforests:

Reconstruction of Wakaleo schouteni challenging the thylacinid Nimbacinus dicksoni over a kangaroo carcass in the late Oligocene forest at Riversleigh, Australia. Image credit: Peter Schouten.

Wakaleo schouteni was the size of a dog and weighed around 23 kg. The species was about a 1/5th of the weight of the largest and last surviving marsupial lion, Thylacoleo carnifex, that weighed in at 130 kg and which has been extinct for 30,000 years.

Its fossilized remains — a near-complete skull, teeth, and humerus (upper arm bone) — were found in the Riversleigh World Heritage Area of remote north-western Queensland.

Wakaleo schouteni spent part of its time in trees. Its teeth suggest that it was not completely reliant on meat but was, rather, an omnivore.

This predator is part of a lineage — the genus Wakaleo — that followed Cope’s rule during the Miocene, increasing in size through time, possibly in response to larger prey that, in turn, evolved as the flora changed as the continent became drier and cooler.

Based on their discovery, paleontologists believe two species of marsupial lion were present in the late Oligocene 25 million years ago. The other, Wakaleo pitikantensis, was slightly smaller and was identified from teeth and limb bones discovered near Lake Pitikanta in South Australia in 1961.

3. Dinizia jueirana-facao, a tree species from the semi-deciduous Atlantic rainforest in Espírito Santo state, Brazil:

The legume genus Dinizia was known, until now, from a single Amazonian tree species, Dinizia excelsa, discovered nearly 100 years ago.

Dinizia jueirana-facao grows up to 130 feet (40 m) in height. Weighing an estimated 56,000 kg, this massive tree is smaller than its Amazonian sister-species and lacks its buttresses, but is similarly impressive.

While large in dimension, the tree is limited in numbers — it is known from only 25 individuals, about half of which are in the protected area, making it critically endangered.

4. The Mariana snailfish (Pseudoliparis swirei), the world’s deepest-living fish:

The Mariana snailfish (Pseudoliparis swirei). Image credit: Mackenzie Gerringer, University of Washington.

The Mariana snailfish is a small, tadpole-like fish measuring a little over 4 inches (11.2 cm) in length yet appears to be the top predator in its benthic community.

It lives at 26,200 feet (8,000 m) below the surface and is endemic to the Mariana Trench, the deepest stretch of ocean in the world that is located in the western Pacific Ocean.

A fish was recorded on camera at an even greater depth, at nearly 27,000 feet (8,143 m) but it was not recovered and could not be confirmed to be the same species.

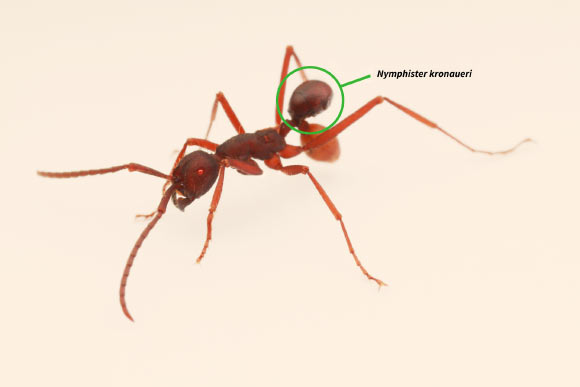

5. Nymphister kronaueri, an army ant-associated beetle species from Costa Rica:

Nymphister kronaueri attached to a worker of the army ant (Eciton mexicanum). Image credit: D. Kronauer.

At about 1.5 mm in length, 16 individuals of Nymphister kronaueri could line up head-to-tail in the space of an inch (2.5 cm).

But their story gets much better. They live exclusively among one species of army ant, Eciton mexicanum.

The host ants, as with other army ants, do not construct permanent nests but are nomadic. In the case of Eciton mexicanum, they spend two to three weeks on the move, making raids each day to capture thousands of prey items, then spend two to three weeks in one location.

While the beetle can move about and feed while the host colony is stationary, it must make the trip with the ants when they are on the move to a new location. The beetle’s body is the precise size, shape and color of the abdomen of a worker ant.

Nymphister kronaueri uses its mouthparts to grab the skinny portion of the host abdomen and hang on, letting the ant do the walking. At a glance, an ant with the beetle onboard appears to have two abdomens but the upper one is a beetle.

Like other myrmecophiles (literally, ant lovers), these beetles must use chemical signals or other adaptations to avoid becoming prey themselves.

6. Ancoracysta twista, a single-celled predatory protist:

Ancoracysta twista: differential interference contrast microscopy of a cell; two flagella, the feeding gullet, nucleus and a posterior digestive vacuole are visible. Image credit: Denis V. Tiknonenkov.

Ancoracysta twista is a predatory flagellate that uses its whip-like flagella to propel itself and unusual harpoon-like organelles, called ancoracysts, to immobilize other protists on which it feeds.

It was discovered in a tropical aquarium at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, California. The geographic origin of the species in the wild is not known.

Ancoracysta twista has challenged scientists to determine its nearest relatives. It does not fit neatly within any known group and appears to be a previously undiscovered, early lineage of eukaryota with a uniquely rich mitochondrial genome.

7. Epimeria quasimodo, a species of amphipod from Antarctic and sub-Antarctic seas:

Epimeria quasimodo, adult. Image credit: Cédric d’Udekem d’Acoz / Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences.

Epimeria quasimodo, about 2 inches (5 cm) in length, is named for Victor Hugo’s character, Quasimodo the hunchback, in reference to its somewhat humped back.

It is one of 26 new species of amphipods of the genus Epimeria from the Southern Ocean with incredible spines and vivid colors.

The number of species, and their extraordinary morphological structures and colors, makes this genus an icon of the Southern Ocean that includes both free-swimming predators and sessile filter feeders.

8. Sciaphila sugimotoi, a mycoheterotrophic plant species from Ishigaki Island, Japan:

Most plants are autotrophic, capturing solar energy to feed themselves by means of photosynthesis. A few, like the newly-discovered Sciaphila sugimotoi, are heterotrophic, deriving their sustenance from other organisms.

In this case, the plant is symbiotic with a fungus from which it derives nutrition without harm to the partner.

In fact, the plant family Triuridaceae to which it belongs consists entirely of such mycoheterotrophs (fungus symbionts).

The discovery of any new species of plant in Japan is newsworthy as the flora is well-documented, so such a beautiful new flower is an exciting addition.

The delicate Sciaphila sugimotoi, just under 4 inches (10 cm) in height, appears during short flowering times in September and October, producing small blossoms.

9. Thiolava veneris, a species of bacterium from the Canary Islands:

Thiolava veneris in its natural habitat. Image credit: Miquel Canals, University of Barcelona, Spain.

When the submarine volcano Tagoro erupted off the coast of El Hierro in the Canary Islands in 2011, it abruptly increased water temperature, decreased oxygen and released massive quantities of carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide, wiping out much of the existing marine ecosystem.

Three years later, scientists found the first colonizers of this newly deposited area — Thiolava veneris, a species of proteobacterium producing long, hair-like structures composed of bacterial cells within a sheath.

Thiolava veneris formed a massive white mat, extending for nearly half an acre (about 2,000 m2) around the summit of the newly formed Tagoro volcanic cone at depths of about 430 feet (129-132 m).

The researchers concluded that the unique metabolic characteristics of the bacteria allow them to colonize this newly-formed seabed, paving the way for development of early-stage ecosystems.

They dubbed the filamentous mat of bacteria ‘Venus’ hair.’

10. Xuedytes bellus, a species of cave-specialized beetle from southern China:

Beetles that become adapted to life in the permanent darkness of caves often resemble one another in a whole suite of characteristics including a compact body, greatly elongated, spider-like appendages, and loss of flight wings, eyes and pigmentation.

Such troglobitic beetles are a prime example of convergent evolution, that is, unrelated species evolving similar attributes as adaptions to similar selection forces.

Xuedytes bellus, a species of troglobitic ground beetle from China, less than half an inch in length (about 9 mm), is striking in the dramatic elongation of its head and prothorax, the body segment immediately behind the head to which the first pair of legs attach.

This species was discovered in a cave in Du’an, Guangxi Province.

Like much of southern China, this is in a vast karst landscape riddled with caves and home to the greatest diversity of cavernicolous trechine ground beetles (family Carabidae) in the world.