Bonobos (Pan paniscus) and other apes, such as common chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and gorillas (Gorilla sp.), have muscles long-believed to be only present in humans and used for walking on two legs (bipedalism), using complex tools, sophisticated facial and vocal communication, according to new research by a Howard University scientist.

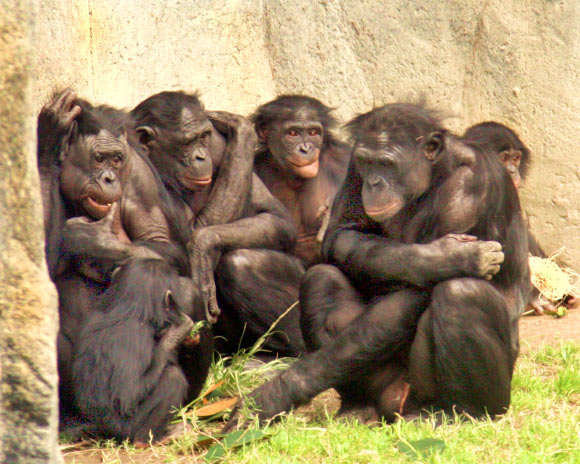

Social gathering of six bonobos at San Diego Zoo. Image credit: William H. Calvin, University of Washington / CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Long-standing evolutionary theories are largely based on the bone structures of prehistoric specimens — and also on the idea that humans are necessarily more special and complex than other animals,” said study author Dr. Rui Diogo, a researcher in the Department of Anatomy at Howard University in Washington, DC.

“These theories suggest that certain muscles evolved in humans only, giving us our unique physical characteristics.”

“However, verification of these theories has remained difficult due to scant descriptions of soft tissues in apes, which historically have mainly focused on only a few muscles in the head or limbs of a single specimen.”

“There is an understandable difficulty in finding primate, and particularly ape, specimens to dissect as they are so rare both in the wild and museums.”

To find enough data to complete this research, Dr. Diogo compiled all previous information on ape anatomy.

He also conducted anatomical research on several bonobos, looking for the presence of seven different muscles thought to have evolved only in our species.

He discovered that these seven muscles were present in apes in a similar or even exact form.

Differences between head muscles of common chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans. There are no major consistent differences concerning the presence/absence of muscles in adult common chimps (left) and bonobos (center), the only minor difference (shown in gray in the common chimp scheme) being that the omohyoideus has no intermediate tendon in bonobos, contrary to common chimps (and humans). In contrast, there are many differences between bonobos and humans (right) concerning the presence/absence of muscles in the normal phenotype (shown in colors and/or with labels in the human scheme). Image credit: Rui Diogo, doi: 10.3389/fevo.2018.00053.

For example, the fibularis tertius muscle, said to be uniquely associated with human bipedalism, was present in half the examined bonobos.

Similarly, both the laryngeal muscle arytenoideus obliquus and the facial muscle risorius — thought to have evolved for our uniquely sophisticated vocal and facial communication, respectively — were present in at least some chimpanzees and/or gorillas.

Published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, the findings open crucial new directions for research and question our understanding of human evolution.

“The picture emerging from this research is that the origin and evolution of human soft-tissue is clearly more complex — and not as exceptional — as first thought,” Dr. Diogo said.

“We need a more thorough examination of why these muscles are present in apes and, in some cases, in just part of a population within a certain species.”

“Are these muscles essential for the apes that have them, as adaptationist evolutionary scientists would argue? Or are they evolutionary neutral features related to how their bodies develop, or simply by-products of other features?”

“Most theories of human evolution give the impression that humans are markedly distinct from apes anatomically, but these are unverifiable ‘just-so stories’,” he added.

“The real evidence shows we are not so different overall. This study highlights that a thorough knowledge of ape anatomy is necessary for a better understanding of our own bodies and evolutionary history.”

_____

Rui Diogo. First Detailed Anatomical Study of Bonobos Reveals Intra-Specific Variations and Exposes Just-So Stories of Human Evolution, Bipedalism, and Tool Use. Front. Ecol. Evol, published online April 26, 2018; doi: 10.3389/fevo.2018.00053