A team of paleontologists from China and the United States has described two shrew-sized mammals that lived during the Jurassic period, between 165 and 160 million years ago.

This is an illustration of Agilodocodon scansorius (top left) and Docofossor brachydactylus (bottom right). Image credit: April I. Neander / University of Chicago.

The first fossil, Agilodocodon scansorius, is the earliest-known tree-dwelling mammaliaform (long-extinct relatives of modern mammals).

Its skeletal features suggest it was an agile and active arboreal animal, with claws for climbing and teeth adapted for a tree sap diet.

This adaptation is similar to the teeth of some modern New World monkeys, and is the earliest-known evidence of gumnivorous feeding in mammaliaforms. The animal also had well-developed, flexible elbows and wrist and ankle joints that allowed for much greater mobility, all characteristics of climbing mammals.

Agilodocodon scansorius was found in lake sediments of the 165 million years old Daohugou Fossil Site of Inner Mongolia of China.

The other fossil, named Docofossor brachydactylus, is the earliest-known subterranean mammaliaform.

This animal lived in burrows and fed on worms and insects. It also has distinct skeletal features that resemble patterns shaped by genes identified in living mammals, suggesting these genetic mechanisms operated long before the rise of modern mammals.

Docofossor brachydactylus was found in lake sediments of the Jurassic Ganggou fossil site in Hebei Province of China.

It had reduced bone segments in its fingers, leading to shortened but wide digits. African golden moles possess almost the exact same adaptation, which provides an evolutionary advantage for digging mammals.

This characteristic is due to the fusion of bone joints during development – a process influenced by the genes BMP and GDF-5. Because of the many anatomical similarities, the scientists hypothesize that this genetic mechanism may have played a comparable role in early mammal evolution, as in the case of Docofossor brachydactylus.

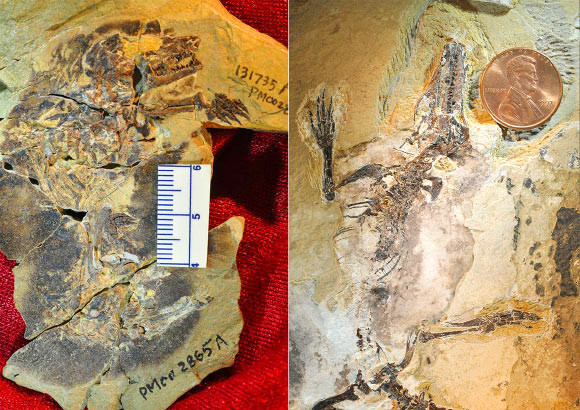

Type specimens of Docofossor brachydactylus (left) and Agilodocodon scansorius. Image credit: Zhe-Xi Luo / University of Chicago.

The spines and ribs of both animals also show evidence for the influence of genes seen in modern mammals.

Agilodocodon scansorius has a sharp boundary between the thoracic ribcage to lumbar vertebrae that have no ribs. However, Docofossor brachydactylus shows a gradual thoracic to lumber transition.

These shifting patterns of thoracic-lumbar transition have been seen in modern mammals and are known to be regulated by the genes Hox 9-10 and Myf 5-6.

That these ancient mammaliaforms had similar developmental patterns is an evidence that these gene networks could have functioned in a similar way long before true mammals evolved.

Early mammals were once thought to have limited ecological opportunities to diversify during the dinosaur-dominated Mesozoic era.

However, Agilodocodon scansorius and Docofossor brachydactylus, and numerous other fossils – including Castorocauda, a swimming, fish-eating mammaliaform discovered in 2006 – provide strong evidence that ancestral mammals adapted to wide-ranging environments despite competition from dinosaurs.

Agilodocodon scansorius and Docofossor brachydactylus are reported in two separate papers published in the journal Science (paper 1 & paper 2).

“We know that modern mammals are spectacularly diverse, but it was unknown whether early mammals managed to diversify in the same way,” said Prof Zhe-Xi Luo from the University of Chicago, who is a co-author on both papers.

“These new fossils help demonstrate that early mammals did indeed have a wide range of ecological diversity.”

“It appears dinosaurs did not dominate the Mesozoic landscape as much as previously thought.”

_____

Qing-Jin Meng et al. 2015. An arboreal docodont from the Jurassic and mammaliaform ecological diversification. Science, vol. 347, no. 6223, pp. 764-768; doi: 10.1126/science.1260879

Zhe-Xi Luo et al. 2015. Evolutionary development in basal mammaliaforms as revealed by a docodontan. Science, vol. 347, no. 6223, pp. 760-764; doi: 10.1126/science.1260880