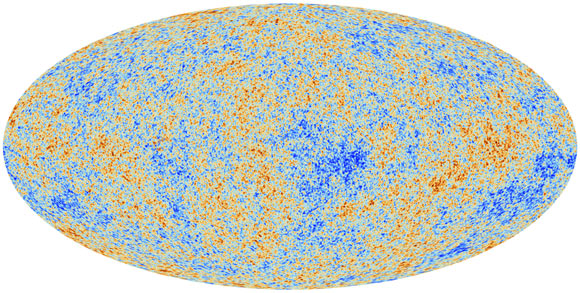

Scientists using ESA’s Planck satellite have released the most detailed map ever created of the cosmic microwave background (CMB).

The image has provided the most precise picture of the early Universe so far. It is based on the initial 15.5 months of data from Planck and is the mission’s first all-sky picture of the oldest light in our Universe, imprinted on the sky when it was just 380,000 years old.

This cosmic microwave background shows tiny temperature fluctuations that correspond to regions of slightly different densities at very early times, representing the seeds of all future structure: the stars and galaxies of today.

“Planck’s high-precision map of the oldest light in our Universe allows us to extract the most refined values yet of the Universe’s ingredients,” explained Planck scientist Prof Lloyd Knox of University of California Davis.

For the first 370,000 years of the Universe’s existence, light was trapped inside a hot plasma, unable to travel far without bouncing off electrons. Eventually the plasma cooled enough for light particles to escape, creating the patterns of the cosmic microwave background. The patterns of light represent the seeds of galaxies and clusters of galaxies we see around us today.

Then these photons traveled through space for billions of years, making their way past stars and galaxies, before falling into Planck’s detectors. The gravitational pull of both galaxies and clumps of dark matter pulls photons onto new courses, an effect called “gravitational lensing.”

“Our microwave background maps are now sufficiently sensitive that we can use them to infer a map of the dark matter that has gravitationally-lensed the microwave photons,” Prof Knox said. “This is the first all-sky map of the large-scale mass distribution in the Universe.”

These new data from Planck have allowed scientists to test and improve the accuracy of the standard model of cosmology, which describes the age and contents of our Universe.

“The CMB is a portrait of the young Universe, and the picture delivered by Planck is so precise that we can use it to scrutinize in painstaking detail all possible models for the origin and evolution of the cosmos,” said Dr Jan Tauber, the European Space Agency’s Planck project scientist based in the Netherlands.

“After this close examination, the standard model of cosmology is still standing tall, but at the same time evidence of anomalous features in the CMB is more serious than previously thought, suggesting that something fundamental may be missing from the standard framework.”

The Universe according to the new data is expanding a bit more slowly than thought, and at 13.8 billion is 100 million years older than previously estimated. The scientists estimate that the expansion rate of the Universe, known as Hubble’s constant, is 67.15 plus or minus 1.2 km/second/megaparsec.

The new estimate of dark matter content in the Universe is 26.8 percent, up from 24 percent, while dark energy falls to 68.3 percent, down from 71.4 percent. Normal matter now is 4.9 percent, up from 4.6 percent.

At the same time, some curious features are observed that don’t quite fit with the current model. For example, the model assumes the sky is the same everywhere, but the light patterns are asymmetrical on two halves of the sky, and there is larger-than-expected cold spot extending over a patch of sky.

“On one hand, we have a simple model that fits our observations extremely well, but on the other hand, we see some strange features which force us to rethink some of our basic assumptions,” Dr Tauber said.

The scientists can also use the new map to test theories about cosmic inflation, a dramatic expansion of the Universe that occurred immediately after its birth. In far less time than it takes to blink an eye, the Universe blew up by 100 trillion trillion times in size.

The new map, by showing that matter seems to be distributed randomly, suggests that random processes were at play in the very early Universe on minute quantum scales. This allows scientists to rule out many complex inflation theories in favor of simple ones.

“Patterns over huge patches of sky tell us about what was happening on the tiniest of scales in the moments just after our Universe was born,” said Dr Charles Lawrence, Planck scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena.